The Real Value of the Negro Leagues Can’t Be Captured in Statistics

5 min read

In my major-league career, I hit 59 home runs. You can look it up; it’s right there in the record books. Baseball statistics offer a comforting solidity. They are concrete, tangible, and unchanging.

Only the truth is, numbers drip with bias, like anything else. In baseball, many of them depend on the whims of an official scoring system. In August 1998, I hit a ball down the third-base line that ricocheted off the wall into foul territory. Dante Bichette, playing left field for the Colorado Rockies, overran and missed the ball as I circled the bases for an inside-the-park home run. The official scorer, though, ruled it a double and a two-base error. Bad play? Yes. Error? Debatable. The Phillies representative in the booth challenged the ruling, and the scorer agreed to change it. But by the time he tried to enter the correction, he’d missed the window to submit a change.

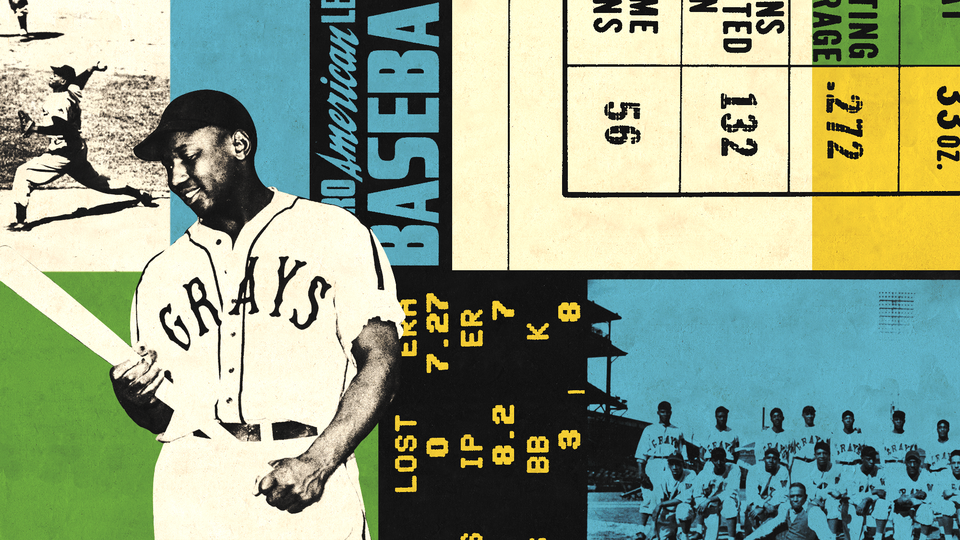

So there I sit, with 59 home runs. I was never going to threaten Hank Aaron’s home-run record, but every homer counts. Despite baseball’s obsession with trying to get the numbers right, we know that the statistics are impossible to keep perfectly. And if there was ever a definitive counter to the old adage that “numbers never lie,” it’s how baseball has treated the Negro Leagues, which operated from 1920 to 1948. In 1969, baseball formed a research committee to consider which leagues of the past would be recognized, and selected six leagues going back to 1876. The Negro Leagues were not among them. Black baseball players literally did not count.

But on Wednesday, Major League Baseball announced that it will finally add statistics from the Negro Leagues into its official record books, changing many of baseball’s long-standing records. The Hall of Fame catcher Josh Gibson, for example, has replaced Ty Cobb as the career batting champion. Some are hailing this change as a long-overdue honor for the Negro Leagues, but I think that gets it backwards. It’s Major League Baseball that’s honored by the inclusion of players such as Gibson.

The change began, oddly enough, with COVID. In 2020, baseball entered a pandemic-shortened season of just 60 games, instead of the usual 162, into the record books. John Thorn, MLB’s official historian, told The Athletic that the 2020 season gave the game a chance to rethink what its numbers meant.

One argument against including the Negro Leagues had long been that its seasons lasted only about 60 games. At one point during my career, I hit safely in 54 of 58 games, batting .364. If that had been my full season, I would likely have made a few leaderboards. Other players have posted even better numbers over a span of that length. But in 2020, baseball crowned a batting champion after just 60 games. If a season that short could enter the record books, why keep the Negro Leagues out?

For a long time, the accomplishments of Negro Leaguers were dismissed as anecdotal. As clearer numbers were compiled, the records set by the players were ironically explained away as the result of not playing against all of the best talent. Black baseball players were nearly erased even though some of the greatest players of the time, like Babe Ruth, acknowledged their excellence. Baseball is now moving to fix that.

And putting these statistics in represents justice in another way, too. During baseball’s steroid era, a number of players juiced their way into the record books. Baseball celebrated their achievements, which brought the fans back. Now a few of those “record holders” will be replaced or pushed down the list by players like Gibson. That represents a kind of poetic justice: The modern stats inflators who stood on the shoulders of the Negro Leaguers have now been pile-driven into the earth, as if the ghosts of the Negro Leaguers wanted to set the record straight from the grave.

I remain a huge baseball fan, and I understand the passion for numbers in our game. But the real value of the Negro Leagues was never defined by statistics. The players were able to create a different sort of value, one that was not predicated on fitting into a society that saw them as inherently inferior. These players found a way to navigate the injustice of segregation, turning it into a means of self-empowerment. Once you discover that you do not need someone to validate you, especially someone who considers you less-than, the power shifts back to you. They had to build their own fan base, marketing plan, and business model. It was the original field of dreams.

But these baseball pioneers had to try for more than “build it and they will come.” They also had to fight the “build it and they will steal it” or, worse, “build it and they will burn it to the ground” that hit everything—Black music, real estate, fashion. Black businesses were well aware that the financial equation was tilted away from them. Even so, they not only survived for decades; they developed incredible talents and skills in the process, both on and off the baseball field.

The stories of many Negro Leaguers are examples of America at its finest (the leagues even included players from the Black international community). Some served our country, despite being relegated to the back of the bus. They endured because they saw how the future should be, not just the injustices of the present. Effa Manley, for example, a co-owner of the Newark Eagles, used her team to raise money to stop lynching. The players did not need half-baked equality to feel empowered and valued. Their communities were already providing that self-worth.

So let’s see this update to the record books as a merger of equals, coming together for the good of baseball. Some numbers may have been lost or remain in question, but at least now we are counting everything that we can. And more important, we are counting everyone whom we long should have counted as worth more than the zero we tried to put on their backs.