What Do We Owe the Frozen Embryo?

7 min read

One of the first documents patients sign when starting in vitro fertilization asks them to consider the very end of their treatment: What would they like to do with extra embryos, if they have any? The options generally include disposing of them, donating them to science, giving them to another patient, or keeping them in storage, for a cost.

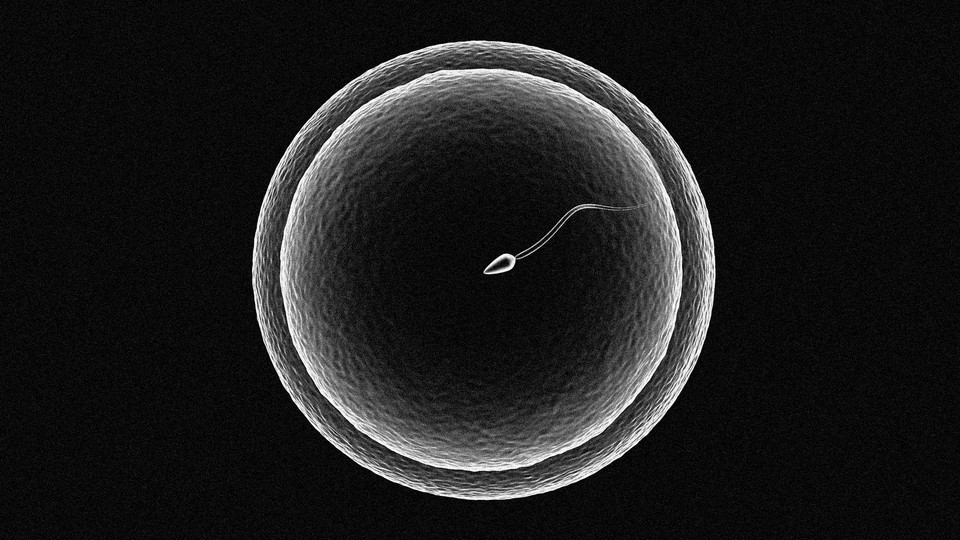

The idea that one might end up with surplus embryos can seem like a distant wish for those just beginning IVF. During treatment, eggs are removed from a woman’s body and fertilized with sperm in the lab to make embryos. These will then be transferred to her uterus, typically one by one, until she gets pregnant. But with advances in reproductive technology, many patients end up with extra embryos after this process is over. Deciding what to do with the leftovers can be surprisingly emotional and morally thorny; even those who are not religious or who support reproductive autonomy might still feel a sense of responsibility for their embryos. So some patients are turning to a lesser-known alternative: a method called “compassionate transfer.” The procedure is essentially an elaborate form of medical make-believe, in which clinicians place a spare embryo in a patient’s body at a time in her menstrual cycle when she is unlikely to get pregnant. It mimics the steps of a traditional embryo transfer, but here, it’s designed to fail; the embryo will naturally flush out.

No one I spoke with in my reporting was sure of compassionate transfer’s origins. One essay published in the South Atlantic Quarterly speculated that the procedure came about to circumvent restrictive IVF laws in countries where clinicians were required to transfer all embryos created via IVF into a patient’s body. Here in the United States, where there are few regulatory limits on fertility treatment, the demand for compassionate transfer speaks to something different: the intense relationship some patients have with leftover embryos, and the lengths they will go to to make peace with their disposal—a peace that, for many other IVF patients, can be elusive.

For the past few years, I’ve lurked on IVF message boards and support groups while going through fertility treatments myself. I’ve observed that although most patients flatly reject the idea that embryos have legal rights—a concept that the the Alabama Supreme Court endorsed in February, when it ruled that embryos were children under state law and that people could be held liable for disposing of them—they also don’t see embryos in the same clinical way as they do other by-products of IVF, such as sperm and unfertilized eggs. Online, women share photos of their embryos and refer to them as “embabies.” I’ve seen patients get tattoos of their embryos and hang watercolor paintings of them in their nursery. They dream that these embryos will become their children, and begin to plot them into family trees. But that hope can morph into grief when embryos fail to implant, when a pregnancy ends in miscarriage, or when patients must determine how to part ways with leftover embryos.

Research shows that many patients feel dissatisfied with the traditional options for dealing with these extra embryos. Thawing and throwing them away can feel inhumane to some. As one woman put it in a 2006 paper on the topic, “If you ask ten women in my situation they probably would tell you the same thing: they don’t want them flushed down the toilet.” Others interviewed said they were distrustful of donating embryos to research, in part because of a fear that the embryos would somehow become children. (There is no evidence to support this.) Giving them to infertile couples also left some patients uneasy about their embryos’ ultimate fate. As the paper found, “For many participants, responsibility entailed that the embryo not ever be allowed to develop into a human being.”

That’s why many simply defer the inevitable and pay to store them. I’ve seen rates ranging from $400 to $1,200 annually, and prices are on the rise. (For reference, my fertility clinic in New York City charges $920 a year.) Today, there may be as many as 1.5 million or more cryopreserved embryos in the United States. About 40 percent will not be used for reproduction. Some people may keep embryos because they’re still trying to have kids, or are unsure if they are completely done, or want to have a backup in case of tragedy. But others know they don’t want more children; a survey conducted in 2006 and 2007 found that 20 percent of that group said they were likely to never take their embryos out of storage. Some of these patients may end up simply abandoning their embryos, failing to pay fees or communicate with clinics. Centers, many of which are already overcrowded due to the rising number of embryos in storage, must then decide by themselves what to do with the embryos, leading to a bureaucratic and ethical mess.

What many seem to desire—and struggle to find—is a way to relinquish their embryos that reflects their significance. To fill this gap, some have created their own makeshift rites. An anonymous questionnaire completed by 703 clinical embryologists around the world found that nearly 18 percent said they’d had patients who wanted some kind of a ceremony for the disposal of their embryos, including reading a prayer, placing a prayer book near the incubator, blessing the embryos, allowing patients to have a moment with them, singing a song to the embryos, and even allowing the embryos to be released to the couple for burial.

Compassionate transfer has much the same purpose. “The point … is the ritual,” explains Megan Allyse, an associate professor of biomedical ethics at Mayo Clinic in Florida, who co-authored a paper arguing that the procedure can be an “ethical extension” of fertility care. As IVF patients go through the process, which follows many of the same steps as a traditional embryo transfer, they may feel that “I’m saying goodbye to this embryo. The embryo is going back into my body where it came from, and everything’s gonna be fine,” Allyse told me.

Research on the procedure—and on embryo disposal as a whole—is scant. One small study of fertility doctors in 2018 found that less than half of doctors who’d heard of compassionate transfer had offered it to a patient. In 2020, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine advised that physicians can honor or decline requests for it as long as they don’t discriminate. The group noted that although the procedure can ease some patients’ “moral distress,” it provides no medical benefit and can be seen as an inefficient use of resources. There’s also a chance, however slight, of infections and unintended pregnancies. “Some clinics feel that it’s out of scope for what they are there to do. Their goal is a pregnancy and managing that pregnancy and supporting it, not what happens afterwards,” Allyse said. Plus, it can be expensive. The 2018 study found that 29 percent of doctors who reported their prices for the procedure charged about the same amount for compassionate transfer as for a traditional frozen-embryo transfer. Insurance doesn’t routinely cover IVF, so most patients have to pay out of pocket. Although some policies do have a fertility benefit, it’s unclear if it would apply to compassionate transfer.

Still, though the costs can be high, they’ll likely be lower than storing embryos for years on end. And the risks associated with the procedure are minimal, Allyse told me, especially when weighed against the psychological stress of not knowing what to do with extra embryos. Sigal Klipstein, a physician at InVia Fertility Specialists, in Illinois, and the chair of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s ethics committee, told me she gets a handful of requests for compassionate transfer every year, which she provides. “Whatever we can do to help our patients feel good about their decisions and complete their families and move ahead … within the limits of science,” she said.

For some, the procedure can be a balm. Klipstein told me about one IVF couple she worked with who tried to create the precise number of embryos for their ideal family size, which was three children. It almost worked. After many cycles, they had two children and one embryo remaining. But before they had the chance to transfer the final embryo, the couple got pregnant on their own. They didn’t want to have a fourth baby, so, after much discussion, they opted for a compassionate transfer. Shortly after Klipstein performed the procedure, she bumped into the couple at a toy store, looking “kind of sad but happy,” walking through the aisles and picking out gifts for their children. Klipstein wondered if they were commemorating their decision to let go of the final embryo, honoring the baby they didn’t have by celebrating the ones they did.