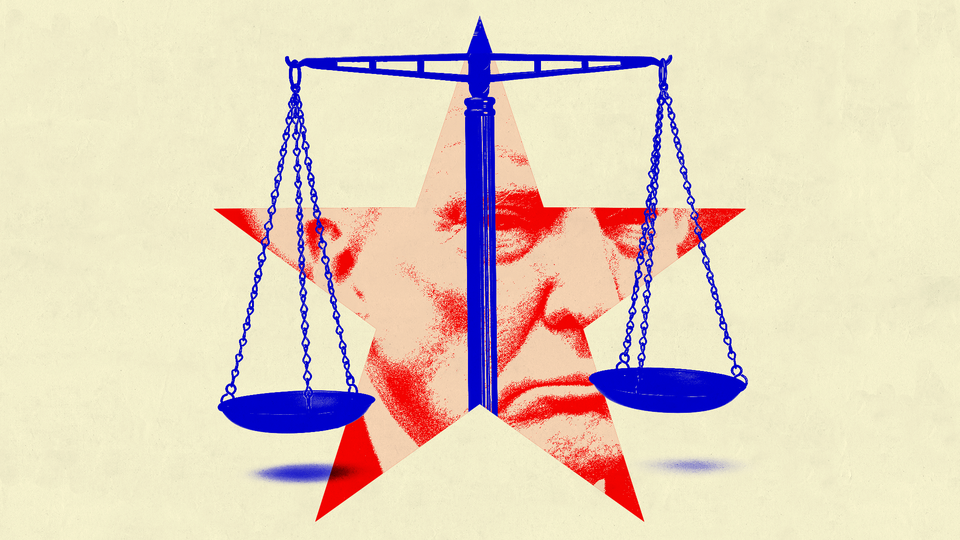

Once a Convict

5 min read

The divide between convicted criminals and the rest of society is sharp, real, and typically enduring. Donald Trump now finds himself on the wrong side of that divide. If he doesn’t win in November (and even, to an extent, if he does), he likely will remain on that barren side of American life, subject to government oversight that normal citizens don’t have to endure, for the rest of his life.

In the federal system, a person is not technically a felon or a convict until sentencing. But Trump was convicted in New York, and that state imposes this designation at the time of the jury verdict. That already entails privations. The New York City Police Department is seeking to revoke his license to carry a concealed weapon. Thirty-seven countries—including Canada and the United Kingdom—have laws prohibiting felons from entering (though they can, of course, make exceptions).

Trump’s fettered status will be driven home today when he has his first command performance as a convict, an interview with the probation office that can cover any number of factors for consideration in the office’s sentencing recommendation.

Chief among these, and most problematic for Trump, is acceptance of responsibility for the crime. Generally speaking, defendants, even unrepentant ones, know to at least feign remorse at this stage. But Trump is constitutionally incapable of admitting guilt. Doing so now would be not only psychologically difficult but politically so, contradicting one of the main planks of his campaign, which is that his conviction was the product of a biased judge, corrupt prosecutors, and a conspiracy he traces all the way to President Joe Biden.

Probation officials are likely to emphasize Trump’s incorrigibility in the report they provide to Justice Juan Merchan, who has a reputation of being tough on white-collar offenders. Personally, I don’t think Trump will serve prison time in 2024 for this particular conviction. If Merchan does impose a sentence of jail followed by probation, my guess is he will then stay the sentence to permit Trump to pursue his one mandatory appeal. Many factors will weigh in favor of a prison sentence at some point, including the 10 violations of Merchan’s gag order, the recent criminal conviction of the Trump Organization, and possibly the finding in the E. Jean Carroll defamation trials that Trump sexually assaulted Carroll (which Trump continues to deny).

Assuming Merchan does impose, and then stay, a “split sentence” of prison plus probation, it will not be the game changer Trump hopes. A stayed sentence does not imply freedom from court oversight. The very best Trump can hope for is the same measure of oversight Merchan already exercises over him, which is the source of authority for the gag order that remains in place. Trump’s conditions of release would remain within Merchan’s discretion, and that’s where they would remain should the appeals court reverse the judgment, assuming the district attorney elects to retry the case, as I think he would.

Straight probation may, in a weird way, prove more constraining for Trump, at least in the short term, during the period of the appeal. I have spoken with half a dozen experienced New York criminal-law practitioners, and although all of them emphasize that the circumstances are unprecedented, they collectively could recall only one single instance in which a state court ordered the suspension of a probationary sentence. Almost invariably, the appeal moves forward while the convict goes immediately into probationary supervision, remaining there unless the case is overturned.

Probation is onerous and its restrictions are determined somewhat arbitrarily, often by probation officers whose recommendations the court tends to accept. It can entail all kinds of potential restrictions and government intrusions, starting with mandatory regular visits to the probation officer. One hundred or more hours of community service is a not-uncommon term of probation. And a long list of standard restrictions applies, including limits on travel, unannounced searches, and drug testing at the probation officer’s discretion. If Trump committed any additional crimes (not ones currently pending), he could be jailed in New York immediately.

Merchan might fashion more forgiving conditions for Trump, but the remaining ones could still be quite burdensome. And if he fails to comply, his probation officer could “violate” him, meaning ask the court to put him in prison.

Once he becomes a probationer, Trump, who all his life has acted as if the rules don’t apply to him, would exist in a “pretty please” world, subject to the ultimate discretion of a judge whom he has trashed ceaselessly and in vile terms.

That state of affairs would endure for the entire probationary term and by that point, one or more of the other criminal cases against him may well have gone to trial. Each of them, especially the two federal cases, is strong, and each carries substantially greater penalties than the New York case. A single additional conviction would make the former president a multiple felon with a criminal history, and the system would treat him more harshly yet. Legal troubles tend to compound.

All of this dramatically increases the personal stakes for Trump of winning in November. If he does, he will be able to simply shut down the federal cases. As for the New York case and whatever remains of the Fulton County case, I think that the Supreme Court likely would and should hold that they must remain in abeyance during his tenure as president.

But even that contingency wouldn’t make them go away. Although we surely would be in an unpredictable world after several years of renewed Trump rule, there’s no apparent way he can make the New York convictions disappear—New York law is New York law, and the president has no formal power over it—meaning that probation and all it entails would be waiting for him at the end of his presidency.

Trump and his supporters look at the convictions as freakish and partisan, and suppose that they can be undone, perhaps by the Supreme Court, which both Trump and Speaker Mike Johnson are asking to step in. But the supposition is fanciful. The convictions are indelible, and their consequences will be enduring. The odds of Trump’s walking away and again being a fully free man are remote.