The Truth About America’s Most Common Surgery

9 min read

In 1957, Ladies’ Home Journal printed a letter from a reader, identified solely as “Registered Nurse,” imploring the publication to “investigate the tortures that go on in modern delivery rooms.” She cited examples of the “sadism” she’d witnessed in an unnamed Chicago hospital: women restrained with cuffs and steel clamps; an obstetrician operating without anesthetic. Among some doctors, the nurse wrote, the prevailing attitude toward women in labor seemed to be “tie them down so they won’t give us any trouble.”

What stands out about the unidentified nurse’s observations, and the personal anecdotes other Journal readers shared in response, “is how women were often treated as an afterthought, a mere container for their babies,” writes the journalist and professor Rachel Somerstein in her new book, Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section. One of the clearest manifestations of this disregard for mothers, Somerstein argues, is the procedure’s ubiquity. The Cesarean delivery can save lives in labor emergencies, and it’s overwhelmingly safe—but in the United States, nearly one in every three births now results in a C-section, including for low-risk patients who don’t need them. For many of these women, the medically unnecessary operation presents a much greater risk to their life than vaginal birth, as well as to their ability to safely give birth again. Invisible Labor traces what Somerstein calls the “cascade of consequences” following a woman’s first C-section, framing the procedure as a symbol of the daunting, interconnected phenomena that make American motherhood so dangerous. She posits that the U.S. health-care system has come to devalue the importance of human touch, relationship building, and interpersonal support, causing our medical infrastructure to fall short of other high-income nations in keeping birthing people safe.

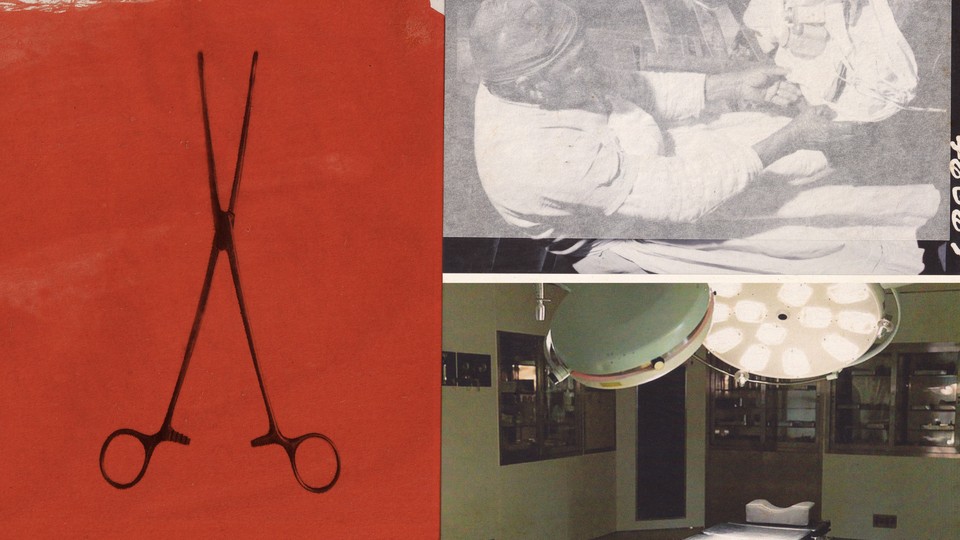

Despite the C-section being the country’s most common surgery, many expectant parents are not encouraged to seek out information about the specifics. This leaves mothers poorly equipped for the procedure’s aftermath, especially when the surgery is unplanned. At the beginning of the book, Somerstein recounts her own emergency C-section, during which the anesthesia failed and the obstetric staff disregarded her anguish. “I felt it all: the separation of my rectus muscles; the scissors used to move my bladder; the scalpel, with which he ‘incised’ my uterus,” she writes. “Yet the operation continued. I was expected to bear the pain.” Invisible Labor follows her search for context about this traumatic experience, and her desire to understand why women’s pain is so often treated as psychological rather than physiological.

Among wealthy nations, the U.S. consistently has the highest rate of maternal deaths, and the CDC has said that some 80 percent are likely preventable. While working on the book, Somerstein “felt nauseated to learn how many people are hurt, damaged, or killed during or after pregnancy or birth—harms borne disproportionately by mothers of color.” By constructing a cultural history of how the C-section became so prevalent, she highlights the extent to which she views childbirth that takes place in medical settings as part of a larger system exerting control over women’s bodies. She extensively cites her interviews with midwives, parents, academics, physicians, and other practitioners. Somerstein, who is white, is notably diligent in her considerations of how racism affects Black mothers and how Black women have informed her thinking on alternate paths forward, relaying her own learning process with refreshing candor.

Invisible Labor makes a compelling case for how the C-section’s widespread application in the U.S. reveals troubling patterns across our reproductive-health system—some of which trace back to slavery and eugenics. Across the country, structural racism in health care and social services makes the risk of death and severe maternal morbidities much higher for Black women than for other groups of women, even when controlling for variables such as age and economic status. (In 2003, the same year that states began adding a checkbox on death certificates to indicate if someone had been pregnant within a year of death, the CDC drew attention to the persistence of racial inequality in maternal health care.) So much of the harm done in American delivery rooms happens because providers dismiss patients’ concerns or don’t communicate with them at all—some providers pressure, or even force, women into having Cesareans. While women of “all races and backgrounds report being coerced into obstetric inventions,” Somerstein writes, “Black women are more likely to experience this particular form of browbeating.”

And as reproductive-justice advocates and scholars have noted, understanding the crisis in U.S. maternal care requires reckoning with the legacy of slavery, an institution that was partly predicated on robbing Black women of their reproductive autonomy. This historical connection is no coincidence: So many medical breakthroughs were only discovered, or widely utilized, because of research that exploited Black people as expendable test subjects. The Cesarean is no different: Historians generally agree that C-sections weren’t used to save a dying mother until the 18th century. (As far back as ancient times, doctors and priests performed C-sections on dead or dying women to save their baby’s life or soul.) Some of Invisible Labor’s most disturbing passages chronicle the change in why Cesareans were commonly performed, a development that “had a critical, and today largely overlooked, wind at its back: the push to bring about more slaves,” Somerstein writes. In the 19th century, the procedures were performed experimentally and without anesthetic on enslaved women, by men who were interested in medical techniques that would preserve their literal property.

Inequalities in health care, and in the workforce, also affect women’s postpartum outcomes. (Today the South has the highest percentages of C-section births; while there’s no one explanation for this, mothers in the South are among the least likely to live in areas where they can regularly access quality health care.) As Somerstein outlines, the most evidence-based solutions to postpartum complications are the same safety nets that the U.S. has historically not invested in. For example, the absence of national paid parental leave makes the U.S. an anomaly among high-income nations, and the current, fragmented model, which is rife with racial inequities, leaves many mothers with no time to recover. The body takes a minimum of 13 weeks to recover, the nurse-midwife Helena A. Grant tells Somerstein. But in a country built on chattel slavery, the default expectation of women, and especially Black women, is still to “have a baby and get right back to work,” Grant says.

Even in cases where a C-section is performed correctly and out of medical necessity, the procedure is still quite brutal. Downplaying the toll of any other major abdominal surgery would seem absurd—yet women who give birth by C-section in the U.S. must also contend with the stigma deeming it an unvirtuous pathway to motherhood. That’s because American cultural ideals overwhelmingly exalt “natural” childbirths—nonsurgical, unmedicated deliveries—as ostensible proof of a woman’s commitment to her child, the one who really matters. That skepticism is even reflected in medieval language about the procedure: One of the earliest known mentions of a Cesarean, from the 13th century, referred to the method of birth as “artificium,” or artificial, Somerstein notes. In her conversations with other mothers, she observed how this tacit hierarchy constrained women’s ability to speak about their traumatic medical experiences. She “saw clearly the cultural expectation that a mother’s pain should be negated by that triumphant moment of union with her baby,” Somerstein writes. “How we simply have no script for what to do with a mother’s pain when it persists beyond that moment: when the baby is fine, but the mother is not.”

Childbirth wasn’t always viewed as a medical event, and what most people in the U.S. think of as a standard delivery—in a hospital, overseen by a physician and nurses—didn’t become commonplace until the mid-20th century. In the 1800s, childbirth was significantly more dangerous than it is now, in part because women had many more children. Most women gave birth at home, attended by midwives who “brought special knowledge to bear,” Somerstein writes.

Often, other women from their communities would come to help encourage the laboring mother and relieve her of domestic duties. Black midwives, enslaved or free, attended to Black and white mothers alike. Men were not allowed in birth rooms, a norm that changed after wealthy white women started seeking out physicians. At the turn of the century, doctors, who were almost all men, brought with them the promise of scientifically advanced methods such as anesthesia to manage difficult births. The doctors’ new tools and treatments sometimes ended up causing the women and their babies grave harm, and maternal mortality rates did not decrease until the advent of antibiotics in the late 1930s. But physician-led birth care was still able to gain a cultural foothold by distancing itself from midwifery—the low-tech, high-touch work of women.

The state of maternal medical care in the U.S. now reflects the consequences of this transition. A once-robust workforce of midwives, many of whom were women of color and immigrants, has been decimated; meanwhile, many hospitals, and the doctors they employ, get paid more for C-sections than for vaginal births. The fact that midwives are not routinely integrated into U.S. birth care, as they are in many other wealthy nations, is one of the many results of racist, state-sanctioned campaigns to devalue the knowledge of women of color. Somerstein lays out how 20th-century legislation restricted, or outright banned, midwives from attending hospital births, and introduced a licensure system that created a de facto racial hierarchy within midwifery. In some cases, the racism used to justify barring midwives from delivery rooms was so overt as to be cartoonish: Somerstein writes that Felix J. Underwood, who served as the director of the Mississippi State Board of Health for 34 years beginning in the 1920s, once “lamented midwives as ‘filthy and ignorant, and not far removed from the jungles of Africa, laden with its atmosphere of weird superstition and voodooism.’”

These bigoted views and arcane laws have had lasting consequences, Invisible Labor argues: Even in states that don’t outlaw midwifery, entering the profession is particularly difficult for Black women. Across the country, the demand for community-oriented birth centers and midwife-led maternal care far exceeds supply—a shortage that is particularly acute in rural areas, where more than half of hospitals no longer deliver babies. In their rush to disempower midwives, anti-midwife crusaders inadvertently created a climate in which neonatal care is less safe for all birthing parents. And after the Dobbs decision, the stakes of legislating reproductive autonomy are even clearer: Legal abortions are significantly safer than childbirth, and rates of maternal morbidity and mortality are much higher in states with abortion restrictions. More than a third of U.S. counties do not have a single obstetrician or birth center, and the shortage is most dire in states with abortion bans. Women living in these states, especially in rural areas, now face massive disruptions to routine maternal care.

Childbirth doesn’t have to be this way. Whether through better insurance coverage for midwife integration or through reducing financial incentives for C-sections, hospital delivery rooms can become less fraught places. Birthing centers, and other modes of community birth, can be tremendously helpful in mitigating the risks that rural women face when hospitals close their obstetrics practices or shut down altogether. But many of the needed shifts can’t happen until insurance companies, legislative bodies, and health-care providers work to improve societal conditions for all birthing people. Thankfully, some of the most valuable interventions in maternal care aren’t technological, surgical, or even medical at all. As Somerstein writes, “Attending to women’s pain could also be rectified by the simple but radical decision to ask women how they feel and listen to the answer.” Invisible Labor is a testament to the transformative potential of respecting women as authorities on their own bodies.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.