The Labour Party’s Lesson for the Democrats

10 min read

They didn’t use emotional slogans. They tried not to make promises they can’t keep. They didn’t have a plan you can sum up in a sentence, or a vision whose essence can be transmitted in a video clip. They were careful not to offer too many details about anything.

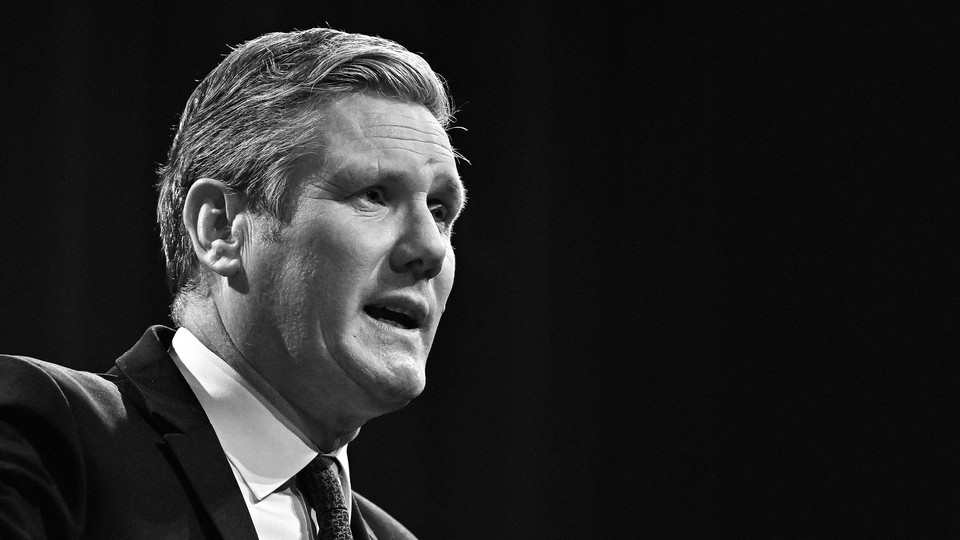

Nevertheless, Keir Starmer and the Labour Party will now run Britain, after defeating two kinds of populism. Yesterday they beat the Conservative Party, whose current leaders promised back in 2016 that simply leaving the European Union would make Britain great again. Instead, Brexit created trade barriers and dragged down the economy. To compensate, the Tories leaned hard into nationalist rhetoric, looked for scapegoats, and shuffled through five prime ministers in eight years. None of it worked: Labour has just won a stunning landslide victory of a kind no one would have believed possible after the last election, in 2019.

Long before this election, Starmer, the new British prime minister, also ran a successful campaign against the far left in his own party. In 2020, he unseated the previous party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, who had led Labour to two defeats. Systematically—some would say ruthlessly—Starmer reshaped the party. He pushed back against a wave of anti-Semitism, removed the latter-day Marxists, and eventually expelled Corbyn himself. Starmer reoriented Labour’s foreign policy (more about that in a moment), and above all changed Labour’s language. Instead of fighting ideological battles, Starmer wanted the party to talk about ordinary people’s problems—advice that Democrats in the United States, and centrists around the world, could also stand to hear.

“Populism,” Starmer told me Saturday, thrives on “a disaffection for politics. A lack of belief that politics can be a force for good has meant that people have turned away in some cases from progressive causes.” We were speaking in Aldershot, a garrison town known as the unofficial home of the British army, where he had just met with veterans. “We need to understand why that is, to reconnect with working people,” he said. “The big change we’ve made is to restore the Labour Party to a party of service to working people. I believe we’d drifted too far from that.”

His official statements from Aldershot, and indeed from everywhere else, used that kind of language too: working people. Service. Change. In his first speech as prime minister, he promised to “end the era of noisy performance.” The rest of his party also talks like this. David Lammy, Britain’s new foreign secretary, described that same philosophy to me last week. “You have to deliver for working people,” he said. “You have to address how they feel about crime, how they feel about health, whether their children will have lives as good or better than them. That has got to be your focus. You cannot get distracted by social media, cancel culture, and culture wars that I’m afraid are totally tangential to most people’s day-to-day lives.”

It’s a differentstory from the one unfolding in other democracies. In a year when millions of Americans are preparing to vote for a serial liar who offers his voters “retribution,” and only days after French voters flocked to both far-right and far-left extremes, the British have just elected an unflashy, unpretentious, hypercautious Labour Party led by a gray-haired prime minister whose manifesto talks about economic growth, energy, crime, education, and making the National Health Service “fit for the future.” The party won without generating huge enthusiasm. Turnout was low, Starmer’s popularity is lukewarm, and many votes went to small parties, including both a far left and a far right that are certainly not beaten for good.

But Starmer’s campaign was not designed to create enthusiasm. Instead, Labour sought to persuade just enough people to give it a chance. This is a shift not only from the Corbyn years, but also from the style of previous Labour governments. Starmer clearly differs from the departing prime minister, Rishi Sunak, a wealthy former hedge-fund manager, but he is also very unlike his most famous Labour predecessor. In 1997, Tony Blair brought Labour from the far left to the center by oozing charisma and courting the British middle class. Blair rebranded his party as New Labour, gave moving speeches, and unleashed a kind of public-relations hysteria that felt fresh at the time. I covered that campaign for a British newspaper, and once interviewed Blair on his campaign bus. Two other journalists were sitting with him as well. We all had different agendas, and there was a surreal, breathless quality to our questioning, as I summarized it later on: “What is your favourite book / will you join the common currency / what do you do in your free time / don’t you think Helmut Kohl is going to eat you alive, Mr Blair?”

Starmer, by contrast, sometimes campaigned as if he had never used the term public relations, and for most of his life, he probably didn’t. His father was a toolmaker in a provincial factory; Starmer himself didn’t run for Parliament until the age of 52. Before entering politics, he was a lawyer who rose to run Britain’s Crown Prosecution Service. In Aldershot, where Blair would have staged a grand entrance, Starmer and John Healey, now the incoming defense secretary, entered the dim room without any fanfare. Ignoring the television cameras lined up against the wall, they sat down at scruffy tables, poured tea, and chatted with the mostly elderly veterans, well out of earshot of the press.

This is clearly Starmer’s personal style. Understated comes to him naturally. Critics might also add opaque. But, again, this is also a strategy. Throughout the campaign, Labour sought to portray itself as a party of men and women who take nothing for granted and will toil ceaselessly on your behalf. “We’ve got to prove ourselves over and over again” is how Rachel Reeves, now the first female chancellor of the exchequer, put it a few weeks ago. The message isn’t exciting, but it isn’t meant to be. And maybe this is what anti-populism has to look like: There is no ideology. The middle-of-the-roadness is the point.

Labour’s 180-degree turn on foreign policy—especially NATO, the transatlantic alliance, and the importance of the military—is part of this story too. Corbyn was skeptical of all of those things, and a faction of the party still is. But Starmer is leaning into them. The meeting in Aldershot was organized by Labour Friends of the Forces, a group that was founded more than a decade ago, faded away in the Corbyn years, and has now been revived. The party also selected 14 military veterans as parliamentary candidates. At the train station in Aldershot, Healey told me that he hoped they would eventually become part of a cross-party veterans’ caucus of the kind that exists in Congress.

The party’s foreign-policy language is also different. When I met Lammy, he had just been to a briefing at the Foreign Office and was on his way to MI6, the foreign-intelligence service (last week, he was still without his own headquarters, and we spoke in a room above a restaurant). Lammy’s parents arrived in Britain as part of the postwar wave of Caribbean immigrants. He was raised by a single mother in a poor London neighborhood, but eventually acquired a master’s degree from Harvard Law School, where he met Barack Obama. He will be, he often says, “the first foreign secretary descended from the slave trade.”

Like Starmer, Lammy is an institutionalist and an avowed centrist. He told me he wants to follow neither “Jeremy Corbyn, preoccupied with the kind of leftist socialism of the last century, the 1970s,” nor the nationalism epitomized by former Prime Minister Liz Truss, who was “trapped in a kind of ideological slash-and-burn worldview.” He uses the term progressive realism to describe this philosophy and talks a lot about facing reality, “meeting the world as it is.” That means recognizing Vladimir Putin’s “new fascism” as well as being “realistic about the support that Ukraine needs.” It also means “meeting Israel as we find it, with a complex political landscape at this time, not as we might wish it to be or as it may have been 30 years ago.”

Both he and Starmer have been to Ukraine and have met its president, Volodymyr Zelensky. Both were quietly planning, as the campaign drew to an end, to attend next week’s NATO summit. Lammy told me he wants to revive the legacy of Ernest Bevin, the Labour postwar foreign secretary who helped create NATO, who was “pretty hardheaded about the dangers of the atomic bomb,” and “pretty hardheaded on the need to bind the U.K. to Europe, to the United States.” He wants people to understand that transatlanticism is not just a Tory quality, but in the Labour DNA too.

Policy toward theEU is a harder call. At the very end of the campaign, Starmer, who supported remaining in the EU, ruled out rejoining in any form “in my lifetime,” and the party sometimes seems to be spooked by the very word Brexit, a hornet’s nest it doesn’t want to poke. Instead, Starmer, Lammy, and their colleagues all speak, without much detail, about better trade relationships and different arrangements with Europe. Reeves recently told the Financial Times that she might, for example, seek to align British regulations with European regulations where it suited particular industries, something the Tories were determined to avoid for ideological reasons: They had promised that Britain would always chart its own course. Nobody voted for Brexit, Reeves scoffed, because “they were not happy that chemicals regulations were the same across Europe.”

Certainly the mood music around U.K.-EU relations will be different. Instead of projecting hostility—Truss once said that the “jury is out” on whether France is a friend or a foe—Lammy hopes to build a new security pact with Europe, and to immediately refresh Britain’s links to France, Germany, and Poland. “I think one of the saddest things of recent years is that the U.K. has drifted,” Starmer told me. “We have to reset on the international stage, and make sure that Britain is seen once again as a country that abides by its word; believes in international law, in international standards; and is respected around the globe.”

Part of that change could have harder edges. Lammy’s team is planning a serious assault on kleptocracy and international corruption, some of which the U.K. facilitates. Oligarchs from Russia and elsewhere have long been attracted to London, not least because buying property anonymously there was so easy, and because the city’s financial experts were always willing to help anyone move money around the world. British overseas territories, including the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands, have become tax havens notoriously used by the autocratic world as well. Lammy told me he wants to go beyond just sanctions on Russia, to stop “the enablers of dirty money: the lawyers, the accountants that enable this behavior.” The billions laundered through the U.K., he has said in the past, are “fueling crime on British streets, runaway house prices, and the severe Kremlin threat.”

The window for this kind of dramatic policy shift might be very small. Labour will have a very brief honeymoon, if it has any honeymoon at all. The impact of Brexit can’t be reversed quickly, years of austerity have run down the health service and schools that Labour wants to rebuild, and the country has no easy source of money to do the kinds of things that would immediately make people feel optimistic and engaged again.

Populism, of both the right-wing and left-wing varieties, hasn’t gone away—on the contrary. Reform, the new anti-immigration party led by Donald Trump’s friend Nigel Farage, fared well in the polls and now has several parliamentary seats. As the second-largest party in many constituencies, it could benefit, in any future vote, from any anti-establishment or anti-Labour surge. Just a day before the election, one of Starmer’s left-wing critics also fired a warning shot in The New York Times, attacking the Labour leader for being “obsequious toward big business, advocating austerity at home and militarism abroad” and condemning Starmer’s “small-minded attempts” to silence critics. Starmer’s tendency to hedge his positions in an effort to occupy the center ground between these poles has made him a lot of enemies.

For now, this balancing act has paid off. Tom Baldwin, the author of a best-selling Starmer biography, told me that to understand the new prime minister, you have to imagine a man standing in a field. “He takes one step forward and stops. A step to the left, and he stops. One step back, two steps to the right, and he stops again. What he’s doing looks weird. It’s inelegant; it’s confusing. But he’s crossing a minefield. And this is the best way to get to the other side.”

Although Labour has been more often out of power than in power over the past century, Starmer did get to the other side. Labour won. And in the end, election victories, not ideological battles, are what matter most.