The Hidden Cost of Gardens

5 min read

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

At first glance, a garden might seem to hold nothing more than the sum of its parts: flowers, greenery, perhaps some fruit trees or vegetable patches. But as Naomi Huffman discusses this week in a review of Olivia Laing’s new book, The Garden Against Time, gardens provoke important questions about land: who owns it, who can use it, and how its privatization, theft, or misuse has harmed people across the world and across time. As Huffman writes, Laing’s book “identifies the social and political forces that have permitted the wealthiest to dictate who has access to land, and to accumulate enormous riches from the immense suffering of others.”

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- Eight books that will change your perspective

- The particular ways that being rich screws you up

- The liminal life of the expat

Jamaica Kincaid, the Antiguan American author and professor who has described her interest in gardens as an “obsession,” would likely agree with that sentiment. This May, she and the artist Kara Walker collaborated to create An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children. In this colorful index of garden life, each letter of the alphabet is assigned to one (or more) words, usually plants or other related concepts and items (“Earth,” “utensil”); an illustration by Walker; and a short description by Kincaid. But the book is much more than a romp through the backyard; it’s a haunting account of the convergence of flora and human history—and it condemns the long, violent history of colonialism.

In A for “amaranth,” a crop native to the Americas, Kincaid writes that in the 16th century, “when the Spaniards were not committing genocide against these peoples they met … they were forcing them to abandon this source of physical and spiritual nourishment and replace it with barley, wheat, and other European grains.” She observes that this was just one of the many atrocities that led to the fall of the Aztecs and the Inca. In P for “papaver,” or poppy, she writes that in the 19th century, the British defeated China in a war over China’s efforts to bar opium imports to the country, which the British wanted to exchange for goods such as silk, porcelain, and tea. Kincaid writes that this “would be as if Colombia and Mexico invaded the United States for the purpose of forcing Americans to buy cocaine and other addictive plants so they could have access to whatever it was the Americans had and they wanted.”

Kincaid’s tone is unforgiving and often biting; she knows exactly where to place the blame and never hesitates to do so. But at times her curious work, which feels very little like a bedtime picture book for children and more like a provocative illustrated pamphlet, appears more philosophical. In one section, Kincaid writes about how decorative gardens—filled with flowers and trees, rather than food to eat—give us room to “think about ‘things’: the little doubts we harbor deep inside ourselves, our hatreds of others, our love of others, the many ways in which we can destroy and create the world and live with the consequences.” In her essay, Huffman also reflects on how the process of cultivating such a garden can inspire meditation on these themes. Laing’s book purports to be “in search of a common paradise.” As Huffman writes, that might “begin with individual acts intended to improve one’s surroundings”: planting a shade-giving tree, perhaps, or sharing with a neighbor the fresh produce one has carefully grown, in hopes that these smaller actions will one day accumulate into something lasting.

What Gardens of the Future Should Look Like

By Naomi Huffman

In her new book, Olivia Laing argues that the lives of all people are enriched with access to land they can use freely.

Read the full article.

What to Read

The Sunset Route, by Carrot Quinn

Quinn’s road is not highways but train lines. Raised in poverty in Alaska by a mother with schizophrenia, the author writes with precision about leaving home at 14 and ending up in Portland, Oregon. There, Quinn dumpster dives for food, finds chosen family among queer punks and straight-edge anarchist communities, learns about gender outside the binary, and discovers that semi-legally riding on freight trains is a means of pleasure, movement, and escape. The Sunset Route alternates between timelines: In one, Quinn is a queer adult train-hopping and, later, long-distance hiking in the Pacific Northwest, where they meet people who are also living on the fringes of America without a safety net. In the other, they recall memories of their childhood, characterized by abuse and anorexia. Ultimately, their writing offers a precise accounting of how their awe for the natural world became their most honest and reliable method to heal. — Emma Copley Eisenberg

From our list: Eight books to take with you on a road trip

Out Next Week

📚 Fog & Car, by Eugene Lim

📚 The Reactionary Spirit, by Zack Beauchamp

📚 The Lucky Ones, by Zara Chowdhary

Your Weekend Read

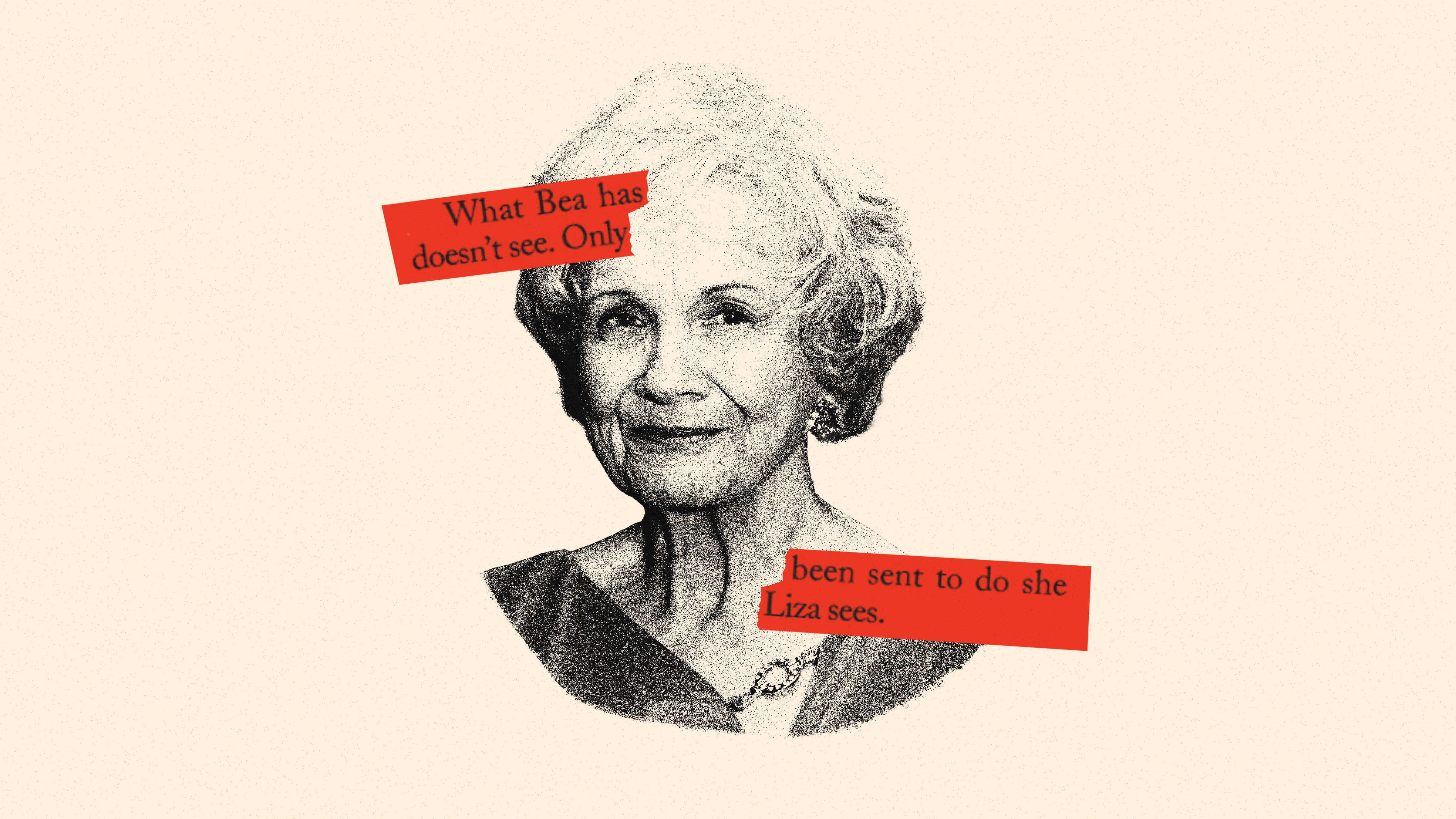

Alice Munro Was a Terrible Mother

By Xochitl Gonzalez

Just as there are terrible, troubled people who are excellent mechanics or stock brokers, there are terrible, troubled people who make excellent art. Perhaps they are even overrepresented. Perhaps, in some cases, it is precisely their troubled terribleness that helped make that art excellent. That, alone, might be reason enough to keep engaging with the art after our idols have fallen. Not blindly, like acolytes. But critically, to see what it was about their work that made it resonate. Art is powerful not because it mirrors only our innate goodness, but rather because it reveals our innate complexity: the delicate balance of love and sin that exists, to varying degrees, within us all.

Read the full article.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Explore all of our newsletters.