Animals Name Themselves. Do They Know Themselves?

6 min read

The best thing language has ever done for us, as far as I’m concerned, is give us the ability to talk with and about one another. Why bother with words if you can’t get your friend’s attention on a crowded street and pull them aside to complain about your nemesis? Language, that is to say, would be largely useless without names. As soon as a group is bigger than a handful of people, names become essential: Referring to someone who shares your cave or campfire as “that guy” goes only so far.

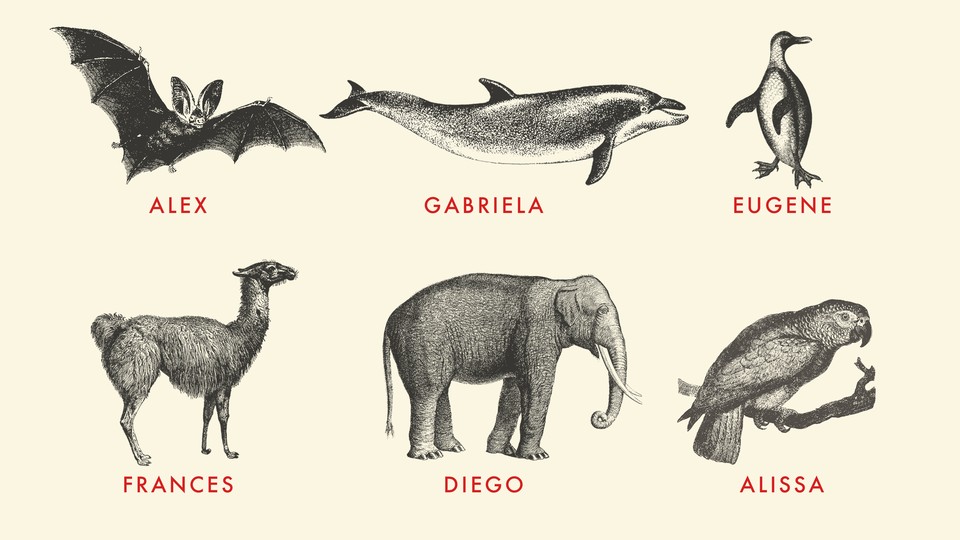

Perhaps because names are so crucial and personal, naming things can feel uniquely human. And until a little over a decade ago, scientists predominantly thought that was true. Then, in 2013, a study suggested that bottlenose dolphins use namelike calls. Scientists have since found evidence that parrots, and perhaps whales and bats, use calls that identify them as individuals too. In June, a study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution showed that elephants do the same. Among humans, at least, names are inextricably linked with identity. The fact that we’re not unique in using them is a tantalizing sign that we aren’t the only beings who can recognize ourselves and those around us as individuals.

Many animals are born with the ability to make a specific collection of sounds, such as alarm calls that correlate with aerial predators or threats on the ground. But “names, by definition, have to be learned,” Mickey Pardo, a postdoctoral researcher at Colorado State University who led the elephant study, told me. Every species that uses auditory names (or namelike identifiers) must necessarily be capable of what scientists call “vocal-production learning”—the ability to learn and produce new sounds or modify existing ones.

The fact that so many different species capable of vocal-production learning use namelike calls—especially species with such different evolutionary lineages—underscores just how important naming must be. In fact, Pardo said, it’s plausible that such creatures gained the ability to learn new sounds specifically for the purpose of naming one another. In the case of humans, Pardo proposed, the skills enabled by naming might even have “allowed our communication system to get more sophisticated until we had language.”

So far, the species that use names (or anything like them), including us humans, are highly social. We all live in fluid groups: Sometimes individuals spend time with family and closely bonded friends or partners, and other times they’re surrounded by strangers or acquaintances. Stephanie King, an associate professor at the University of Bristol, in England, and a lead author on the bottlenose-dolphin paper, told me that, in such societies, names serve a practical function. They allow you to track and address your social companions, whether they’re nearby or you’ve become separated from them. That’s especially helpful if you rely on others’ cooperation to hunt or care for young. “For dolphins, it’s important to keep track of who you can rely on to assist you in times of conflict,” King said.

Names can also have more sentimental purposes. Among elephants and dolphins, Pardo said, name calls may be a sign of closeness: Individuals of both species appear likelier to use the names of other animals they’re bonded to. Humans, too, can use names to project or create intimacy. For example, in one study, people were likelier to do a favor for someone who remembered their name. When I meet someone and want to stay in touch, I go out of my way to learn and remember their name.

This, perhaps, gives some credence to Dale Carnegie’s advice in How to Win Friends and Influence People to learn others’ names: “A person’s name is to that person the sweetest, most important sound in any language.” Personal experience supports that theory. Many times, my own name, Tove, has caused me trouble. Because it’s Scandinavian, it rhymes with nova, not stove, which means I spend countless hours of my life pronouncing and spelling my name for people when I’d rather talk about anything else. But as much as that annoys me, I’ll never change my name—it’s mine—and I care that others get it right.

For humans, the significance of names is inseparable from concepts of identity and individuality. We could walk around describing one another with labels—American, woman, child, baker, pedestrian—but people generally don’t like to be addressed or referred to that way. “It makes you feel less than human,” Laurel Sutton, the president of the American Name Society, told me, perhaps because such epithets fail to differentiate an individual from a group. “We are very individualistic as a species.”

Scientists don’t yet know whether names have developed such deep significance among other species. But the mere existence of naming among animals is a hint that they have a sense of themselves as separable from the world around them. It’s not the first clue that scientists have had of such a possibility. Since the 1970s, chimpanzees—and, by some accounts, dolphins and even reef fish—have passed the controversial “mirror test,” in which an animal reacts to a mark placed on its own body that’s visible in a mirror. But touching a red dot on your forehead is still very different from understanding that every member of your species is an individual.

Of course, names and the mirror test are far from the only ways that animals demonstrate an awareness of something that approximates identity. Individuals from all sorts of species can recognize their offspring and mates. Dolphins may be able to recognize familiar companions based on their urine in the water. Bats likely use signatures encoded in echolocation calls to distinguish between other individuals.

As tempting as it may be to find analogues for human behavior among animals, King cautioned against putting too much stock in such arguments. “It’s more interesting to look at how and why the animals behave as they do in their system,” she said. Perhaps studying animal naming behaviors might be most valuable for the ways it allows scientists to learn more about other species and how they adapt to their environments. For example, King said, a dolphin’s signature whistle—its name—is discrete, whereas an elephant name call encodes other information along with the elephant’s identity. This difference may have arisen, King posited, because of the way sound travels underwater or how pressure changes dolphins’ ability to vocalize. But it could also stem from the fact that dolphins more regularly encounter a wider number of individuals, which means they need more efficient introductions. Finding the answer would tell scientists more about these species’ societies and evolutionary needs—not just that they do something similar to humans.

Still, I can’t help but feel a sense of connection when I learn that a new species has joined the ranks of namers. As the botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, “Names are the way we humans build relationship, not only with each other but with the living world.” And other species’ names make me hope for the possibility that those relationships might become more reciprocal. The thought of someday being able to address an elephant in a way it can understand is downright magical. To say, “Hello, I’m Tove. Please tell me your name.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.