The Books That Keep Readers Awake at Night

5 min read

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

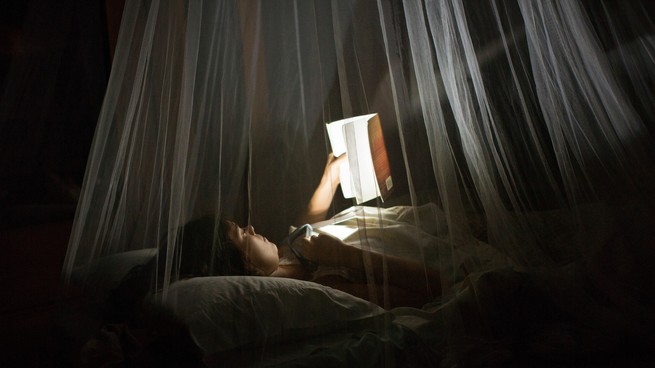

Every person alive likely knows how it feels to lie in the dark, willing sleep to come but failing, minute after minute, to drift off. Even if you’re in bed next to someone, once you close your eyes, you’re isolated, with nothing but your own racing thoughts to keep you company. This week, M. L. Rio, who has struggled with insomnia since graduate school, offered a list of books to comfort the restless in the lonely predawn hours—and included a few that might, hopefully, lull them into dreamland. Her list was inventive and instructive, but it made me think of an adjacent category of books: the ones that keep you awake far past your bedtime.

But first, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- “Cornucopia,” a poem by Natasha Rao

- The cheapness of luxury

- “On Love,” a poem by Andrea Cohen

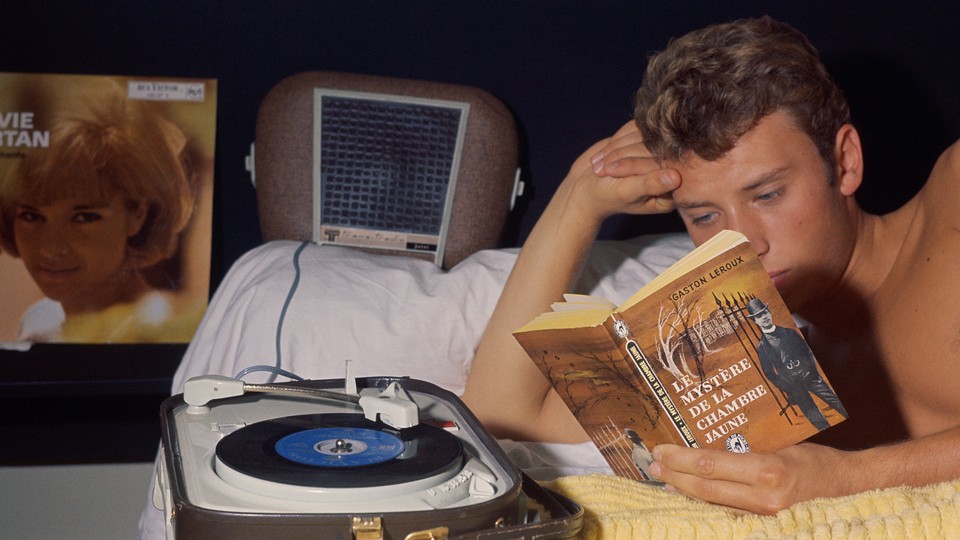

On the whole, I’m blessed with the ability to sleep peacefully once I lay my head down. However, I do not always possess the discipline to forgo short-term gratification for next-day alertness: I’m an inveterate bedtime procrastinator, always delaying lights-out for another episode, a few more scrolls, or, especially, just one more page. And this tendency is exacerbated when I’m reading a certain kind of book—a knotty, exciting, suspenseful one with a strong voice, especially a novel that’s older (and therefore has plot details littered across the internet, ready to spoil a too-curious traveler).

These books keep me up at night because I’m racing my own impatience. I wanted to know what would happen in The Secret History, and I knew that if I didn’t finish it quickly, I’d end up stumbling across a twist I didn’t want ruined. I raced through Pale Fire for the same reason—I desperately wanted to read critical writing picking apart the book’s images and implications, but doing that would likely have ruined the reveals about Charles Kinbote’s identity that I now know are much better if unspooled slowly and subtly. I stayed up until 2 a.m. reading John Fowles’s The Magus partially because I was captivated by its narrator, Nicholas Urfe, a self-important layabout with very little self-awareness, but mostly because, just like Nicholas, I’d become obsessed with the mysterious Greek recluse Conchis and hoped to understand his secrets. And who, I wondered, really was the titular character in Piranesi? I needed to find out, and because I work in the daytime, this frequently meant reading until far too late at night.

These books are invariably fiction—I find that even the most compelling true-crime account or dramatic memoir can wait for the morning, possibly because the events inside have already played out. But in a novel, the action is suspended in time, always ready to stop or start as the reader puts down and returns to the story. This makes getting to the end for the first time extra special, and it’s what pushes me to stretch one day long into the early hours of the next one.

Seven Bedside-Table Books for When You Can’t Sleep

By M. L. Rio

These titles can offer another voice in the darkness, ready to soothe a restless mind.

Read the full article.

What to Read

The Enchanted April, by Elizabeth von Arnim

When The Enchanted April was first published, in 1922, it became a best seller in both England and the U.S. and inspired not only film and theatrical adaptations but also a rash of trips to Italy. (We might think of this as a precursor to the Eat, Pray, Love phenomenon.) The novel describes four women who feel compelled to spend the month of April together in Portofino. The plot is set in motion when the self-effacing, awkward Lotty Wilkins sees an ad in a newspaper on a rainy winter day in London, addressed to “Those who Appreciate Wistaria and Sunshine,” and has a eureka moment: She should rent the advertised house. She manages to convince three more women—an acquaintance from her ladies’ club and two strangers she scrounges up—to join her. Later, thanks to a month spent among sea and sun and flowering vines and cypress trees, the women all have various epiphanies of their own, returning to forgotten selves and admitting their true desires, in life and in love. The novel is a reminder that sometimes you have to go far away from home to come home to yourself. (It’s also a reminder to visit Italy in the springtime.) — Pamela Newton

From our list: Eight books that will change your perspective

Out Next Week

📚 The Quiet Damage, by Jesselyn Cook

📚 Liars, by Sarah Manguso

📚 A Passionate Mind in Relentless Pursuit: The Vision of Mary McLeod Bethune, by Noliwe Rooks

Your Weekend Read

The Two Marys

By Elliot Ackerman

The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig’s 1932 biography, Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of an Average Woman … [paints] a portrait of an aristocratic elite that cannot fathom the dissolution of a dysfunctional old regime even as it occurs before their eyes. In a second biography, Mary Queen of Scots, Zweig is concerned with questions of legitimacy—what happens to a society when the state’s authority is habitually called into question, as Mary Stuart called into question Queen Elizabeth’s reign as a Protestant monarch. The two books felt to me like the perfect supplemental reading last month, amid news coverage of the trials of Hunter Biden and Donald Trump, as if Zweig were commenting on our time.

Read the full article.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Explore all of our newsletters.