Even an Assassination Attempt Became Eerily Normal

7 min read

He had closed down the office of the Butler County Democrats and suspended local campaigning. And nearly every hour since a 20-year-old man had tried to assassinate Donald Trump at a rally on the edge of town, Phil Heasley, a party co-chair, had been fielding calls from members wondering what dark phase American politics might be entering now.

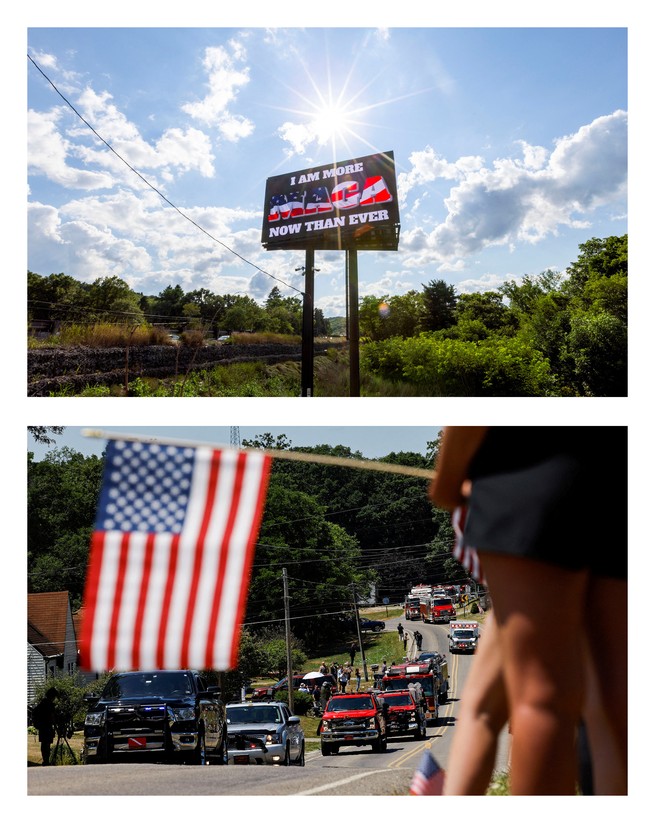

Someone texted him a photo of a truck with a huge digital billboard that read Democrats Attempted Assassination. Someone else sent a screenshot of what the local GOP member of Congress, Mike Kelly, had posted and quickly removed from Facebook: “We will not tolerate this attack from the left.” Neighbors were spray-painting fight on streets; fresh Trump flags and huge Trump signs were going up in yards and fields and on the cinder-block sides of auto shops along rural roads in this corner of western Pennsylvania. Someone suggested installing a panic button inside the party’s glass-front office in downtown Butler, where Heasley was now opening a not-very-secure door. The answering-machine light was blinking.

“Let’s see what we have,” he said, imagining the worst.

Beep: “I’m interested in volunteering … ?”

Beep: “Please call my cellphone as soon as you can. It’s urgent.”

Beep: “This is Carl in Columbia, South Carolina, and I just wanted to acknowledge the family of the man who got killed. Wanted to send some money to his family for funeral expenses. If you could please be so kind …”

Relieved, Heasley wrote down the numbers. This was on the Wednesday after the Saturday of the assassination attempt. Already, the escalating threat of violence was being folded into day-to-day life. He himself had watched the shooting on live television from his family’s cabin on Lake Erie, then gone down to the dock where he often hung out with his Trump-loving neighbors. “So what do you think?” they’d asked him, and he’d tried to read their faces. “I have no thoughts,” he decided to tell them, and they reverted to their Saturday-night custom, sharing beers and singing Frank Sinatra songs. The cycle of news moved on to the Republican National Convention and questions around Biden’s candidacy, leaving people in Butler County with whatever rituals might ease anxiety.

In a front yard across the street from the rally site, a white tent popped up Tuesday where pastors offered prayers, telling a few people who stopped by that they were “citizens of heaven.” This lasted a few hours, until one of them said, “Well, I guess it’s time to pack it in.”

At the rally site itself, conspiracy theorists with cameras and notebooks began arriving, replacing federal investigators and television crews.

At a firehouse in the township of Buffalo, volunteer firefighters did what they did when one of their own died, in this case Corey Comperatore, a former chief whom the shooter had killed at the rally. They prepared their trucks for the funeral, polishing chrome, placing black electrical tape over the eyes of the buffalo on the town shield.

An hour away, in the neighborhood where the would-be assassin grew up, people said what people say when they have no explanation. They’d seen the boy here and there. They never imagined such a person living among them, though their upper-middle-class neighborhood was the very kind of place where young white men have grown up to be lone shooters. Not even the FBI has been able to offer a motive beyond the one implicating all of society—another young man who absorbed the violence of American life until he engaged in it himself.

In the Democrats’ office in downtown Butler, Heasley understood what happened as political violence, even if it had the random quality of a mass shooting: “I saw a poll where something like 58 percent of Americans expected this to happen.”

He was among the 58 percent. He’d knocked on doors for President Barack Obama in 2012, and had seen nooses with Obama signs hanging from trees. People threw trash in his yard when he ran for township supervisor a couple of years ago, and he’d finally gotten his concealed-carry permit.

“I guess this is normal politics now,” Heasley said. So when local Democrats met to decide whether they should set up their usual booth at Horse Trading Days, a festival in nearby Zelienople, he argued yes. Police would be there.

“Visibility is still important,” he said.

On Thursday morning, the United Republicans of Butler County set up at one end of Zelienople’s Main Street, and at the other end, two volunteers with the Butler County Democrats set up a tent and table next to a woman selling homemade hot sauce.

“You should be ashamed of yourself,” the woman said to Karen Barbati, one of the Democratic volunteers, as she secured the tent poles in the grass.

“What do you mean?” Barbati said.

The woman ignored her and wheeled a metal cart between her booth and theirs. Soon, people began arriving for the festival, which now had heightened security. At the Republican table, volunteers set out Bye-bye Biden signs and what was left of circa-2016 Trump gear, including black T-shirts with a huge image of a Colt .45 labeled Trump, and the words Because the 44 didn’t work for 8 years, a reference to Obama.

At the Democrats’ table, a volunteer set out a basket of small buttons with rainbows and peace signs. She hung up posters with headings such as Freedom From Gun Violence and Freedom to Have a Safe Infrastructure, each of which had long blocks of small type underneath explaining what Biden had delivered: $6,492,797 for Butler County Community College; $1,487,092 for Callery Bridge over Breakneck Creek; and “the first major gun-safety legislation in 30 years,” a politics that assumed people wanted policy details over emotion.

At the Republican table, a volunteer named Rick Markich was saying, “I would not want to be trying to figure out how to approach the public if I were a Democrat.”

At the Democratic table, a volunteer was saying to a man in a Trump hat, “Hello there, enjoying this weather?” and to a woman who walked up to the booth, “You can take a button” and “This is a form you can use to register.”

Back at the Republican table, a small crowd had gathered, and in between talking about the lovely weather and pastries, a woman was saying, “We were there,” referring to the rally. “We saw him go down.”

“I was 15 feet from the gentleman who died,” Markich said, referring to Comperatore. “Saw them carry him out. He was lifeless.”

“We were screaming,” the woman said in the bright afternoon.

“At first we thought he was the shooter,” said Markich, who was wearing a Trump hat now painted with the words Fight, fight, fight, and the date July 13, 2024. “We thought patriots had taken him down. In reality, they were trying to save that gentleman.”

“I like this Bye-bye Biden,” the woman said, moving on from that conversation. “But I’ll take a Drain the swamp.”

People walked by eating ice cream and drinking beer. People talked about hearing gunshots and seeing blood. People chatted about their goldendoodle dogs and diving for cover.

In another town an hour to the east, the public viewing for Comperatore was getting under way, a long line of people inching up a grassy hill past rows of American flags, to a community hall where two snipers were positioned on the roof, and plates of cookies were set out on tables inside.

In Zelienople, meanwhile, Barbati was saying that she had a Biden-Harris sign in her yard, and had gotten used to the man who drove by her house most days around 3:15 in the afternoon and yelled “Trump!” Another Democratic volunteer was saying she was not afraid, but after everything that had happened, she was going to get a gun from her son.

The wind blew, and the smell of barbecue drifted into the late afternoon. The volunteers sat in folding chairs and watched people walking from the doughnut booth to the hot-sauce tent. A man in camouflage shorts paused, stared at the Democrats for a moment, and walked on. A woman rushed over.

“I’m so glad I found you guys,” she said, explaining that she was new to the area.

At the Trump table, a woman considered a Trump sign for her car, then stopped herself. She lived in a country where a protester had been run over by a car during a neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia; and the U.S. Capitol had been stormed on January 6; and the speaker of the House’s husband had almost been bludgeoned to death; and now Trump, who had mocked and encouraged much of that, had nearly been assassinated in her hometown. She decided against the sign.

“You never know when you might get a bullet,” she said to a volunteer, who replied casually, “Yeah, I almost got killed Saturday.”