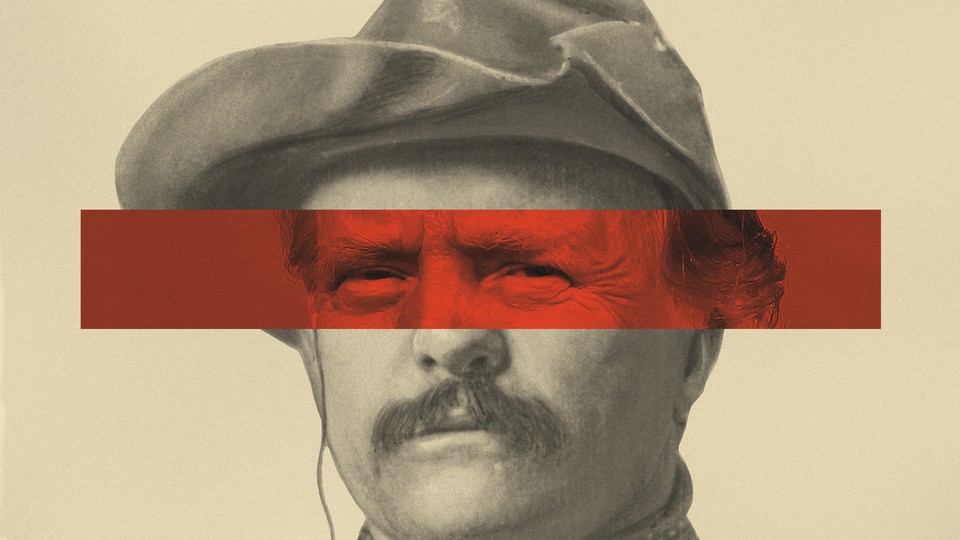

Trump Wants To Be a Bull Moose

8 min read

The ghost of Theodore Roosevelt, cowboy hat still on his head, was riding circles last week around the convention center in Minneapolis where the Republican National Convention was held. The location was a fitting one for him to haunt, because as we’ve now been reminded, this was just down the street from where T.R. was shot in October 1912 while on the campaign trail. He famously continued with his planned speech, a bullet lodged in his chest, opening his suit jacket to reveal his bloody shirt. “It takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose,” he said, the equivalent of Donald Trump’s fist pumping the air moments after he was wounded in his own assassination attempt a week ago, as he shouted, “Fight! Fight! Fight!”

No wonder that Theodore Roosevelt—smiling, robust, tough—remains popular in the American imagination. And it’s no surprise that Elon Musk and Don Trump Jr., among others, quickly leaped for the allusion, especially given that Trump’s then-opponent was so broadly seen as confused, weak, and tired. Grafting current candidates and presidents onto past ones is a fun parlor game for politicos and cartoonists (I distinctly remember Barack Obama rendered variously as Lincoln, JFK, and FDR). But understanding what aspect of the American lexicon a politician is trying to borrow in their image construction can be revealing—I realized as much after I asked several historians to analyze Trump’s image alongside Roosevelt’s and describe the alignments and slippages.

Mostly, the two men couldn’t be more different, including with regard to their political philosophies and character—Roosevelt was known to read a book a day; Trump, not so into the whole reading thing. But when it comes to how they conceived of power and how an American president projects it, Teddy, it turns out, makes for a telling comparison.

Masculinity of a certain vintage is the ostentatious connection between the two. Roosevelt’s public persona was all about his physical solidness. “Roosevelt is the cowboy; Roosevelt is the Rough Rider who volunteered for war when he was 40 years old; Roosevelt is the big-game hunter in Africa; Roosevelt explored the Amazon and almost died doing it,” said Edward Kohn, who has written two books on Roosevelt, including Heir to the Empire City: New York and the Making of Theodore Roosevelt. “So Roosevelt was the epitome of manliness and masculinity and the rough-and-tumble,” he told me. “And that’s absolutely part of the Republican brand, for a number of years now.”

The historian Sean Wilentz put it even more succinctly: A desired projection of “virility” is what Trumpists hope might unite the two men. At a convention where one common refrain was that the Democrats “can’t even define what a woman is,” Trump sought to imprint himself as a man’s man, sitting stoically, his wounded ear bandaged, raising his fist to salute the crowd. (Never mind that a true stoic would never recount his own injury in such solipsistic detail—when Roosevelt described his own assassination attempt, five minutes after it happened, it was with a focus on the “coward” who had shot him, and he even pulled off a joke: “Don’t you make any mistake. Don’t you pity me. I am all right. I am all right, and you cannot escape listening to the speech either.” There was no talk of “divine intervention.”)

I was curious about the extent to which Roosevelt had constructed this image of the weight-hoisting, lion-killing alpha male for himself. After all, it’s widely accepted that he did push himself into becoming a physically tougher person, exercising in order to transcend the puny, asthmatic young boy he was. It’s possible that his toughness and resilience were more about mind than body, that the risks he took in his life are what turned him into that person. Candice Millard, who wrote The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt’s Darkest Journey, described Roosevelt to me as “the embodiment of masculinity” in his day.

Millard also told me a story from Roosevelt’s youth, when he says his father instructed him, “You have the mind, but you don’t have the body; you need to make your body, and you need to make yourself, physically strong.” From his earliest memories, Roosevelt learned that he had to test his limits. “He boxed, and he would swim naked in Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C.,” Millard said. “He played tennis, but he wouldn’t let anybody photograph him playing tennis, because he thought it wasn’t a masculine-enough sport.” But none of this was necessarily politically calculated, Millard said. After a lifetime of trying to be braver and more daring than he was naturally inclined to be, it became “just who he was,” she said. One of Roosevelt’s most famous speeches, from 1899, talked about the joys of a “strenuous life.”

Roosevelt and Trump were both born in New York City—to date, no other U.S. presidents can claim the same—and both chose to develop personas that would appeal to people beyond their very particular urban, and privileged, upbringings. Where Roosevelt used his time out West to justify wearing a cowboy hat, Trump used his appearance on The Apprentice to play the part of the quintessential cutthroat New York businessman—providing a template for American strivers everywhere.

Below the surface level, their political ideologies could not be further apart. Roosevelt was a progressive. He’s best remembered for regulations and antitrust suits to temper free-market capitalism (famously his crusade against big oil). He believed in the necessity of a safety net. And he only got more progressive as he aged. When he was shot in 1912, it was during the campaign for his political comeback. After serving two terms, he ceded the Republican Party to Howard Taft, but then became angry with its conservative direction, and returned to contest the nomination in the next election. When he wasn’t chosen as the Republican candidate, he started his own independent Bull Moose Party. His policy prescriptions anticipated what his cousin Franklin would do two decades later—he was talking about creating something very much like Social Security long before its time, even imagining a public role for health care. In fact, the bullet that nearly killed him was slowed down when it hit his steel glasses’ case and a 50-page speech in his coat pocket; it was titled “Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual.”

When it came to foreign affairs, Roosevelt was, as Robert Kagan told me, “the original internationalist.” Kagan wrote about Roosevelt’s presidency in his book The Ghost at the Feast: America and the Collapse of World Order, 1900–1941. There was a moral interventionist approach to his foreign policy that was new in American history—among other things he fomented a revolution in Panama so he could build the Panama canal. On some issues of race, he was a progressive for his time, famously inviting Booker T. Washington to a meal at the White House. (Though he also has a reputation for having perpetuated racist stereotypes during the Spanish-American war.) A man who strongly identified with New York City in the heyday of mass immigration, he was extremely pro-immigration. Basically, Kagan said, Roosevelt “was the opposite of everything the Republicans now stand for.”

On economic policy, even Trump would seem to agree that Roosevelt is not his man. Instead, Trump has been pointing with reverence lately to William McKinley, the president whose assassination elevated Theodore Roosevelt (Roosevelt’s shooter said that McKinley’s ghost told him to pull the trigger). Trump particularly likes McKinley’s use of heavy tariffs on imports—Trump has dubbed him the “Tariff King”—as a possible model for doing away with a progressive income tax.

If the differences abound, there is, however, one aspect of Roosevelt’s presidency that aligns with Trump’s ambitions in absolute terms. Roosevelt greatly expanded the power and scope of the executive branch. H. W. Brands, the author of T.R.: The Last Romantic, pointed me to Roosevelt’s 1913 autobiography, in which Roosevelt says, explicitly, that he will exercise his power freely, that unless the Constitution says that he can’t do something, he can do it. In all the history of the American presidency, this bold assertion was new.

As Roosevelt wrote, “My view was that every executive officer, and above all every executive officer in high position, was a steward of the people bound actively and affirmatively to do all he could for the people, and not to content himself with the negative merit of keeping his talents undamaged in a napkin.”

To my ears, this sounds … Trumpian. Brands offered me a laundry list of things that Roosevelt did with that power that no president had dared to do before, including intervening in a labor strike on behalf of workers and designating millions of acres of land in America the way he saw fit (as protected national forest). This all sounds like a useful exercise of power—and in contrast with Trump, not for its own sake but to benefit the citizens Roosevelt served and the land he loved—but even in his time, this sort of presidential prerogative felt worrisome. As astute an observer as Mark Twain warned that Roosevelt was“ready to kick the Constitution into the backyard when it gets in the way.”

Though the presidency has now taken the shape that Roosevelt gave it, and many presidents since have tried to push the limits even further, it’s no surprise that the chief executive who first acted without anyone’s permission might be a role model for the kind of leader Trump was and wants to be. “Roosevelt had that energy,” Brands reiterated. “And somebody like Donald Trump, who is an old man but is trying to project his own energy, would naturally want to use Roosevelt as a model.”

In this sense more than any other, the desire to emulate Teddy is intuitive. To do what Trump wants to do with power takes a supreme level of self-confidence. And looking back at American history, Roosevelt stands out as a leader who had exactly that absurd degree of faith in his own abilities. Millard told me that her favorite quote about Roosevelt came from the naturalist John Burroughs, who said about Roosevelt that “when he came into the room it was as if a strong wind had blown the door open.”

“This is so vivid, and it’s so Roosevelt,” Millard said. “And whatever you think about Trump, it’s also true that you can’t ignore him. I mean, he blows the door open.”