The Court Fools Itself

8 min read

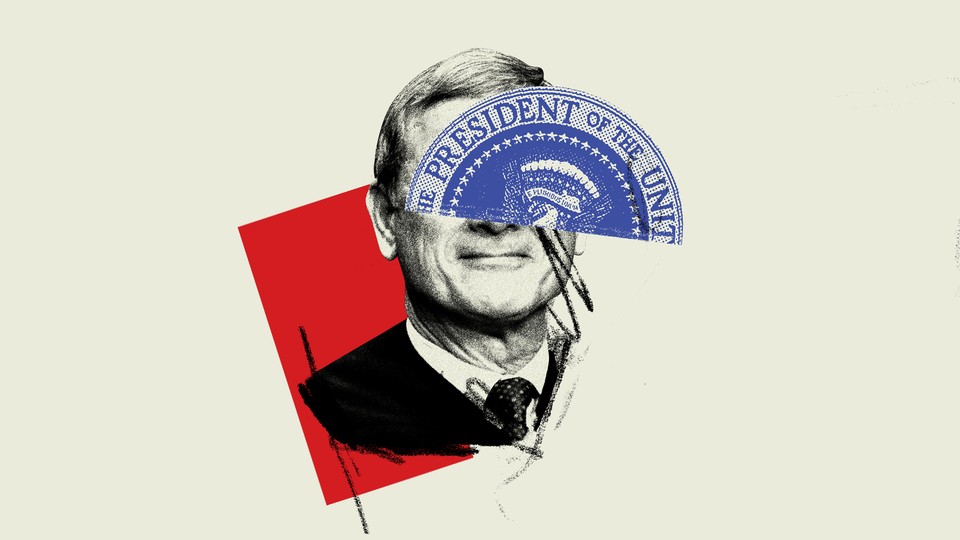

The Trumpist justices on the Supreme Court had a very serious problem: They needed to keep their guy out of prison for trying to overthrow the government. The right-wing justices had to do this while still attempting to maintain at least a pretense of having ruled on the basis of the law and the Constitution rather than mere partisan instincts.

So they settled on what they thought was a very clever solution: They would grant the presidency the near-unlimited immunity Donald Trump was asking for, while writing the decision so as to keep the power to decide which presidential acts would be “official” and immune to criminal prosecution, and which would be “unofficial” and therefore not. The president is immune, but only when the justices say he is. The president might seem like a king, but the justices can withhold the crown.

The Supreme Court’s ruling on presidential immunity combines with its regulatory decisions this term to remake the executive branch into the ideal right-wing combination of impotence and power: Too weak to regulate, restrain, or punish private industry for infractions, but strong enough for the president to order his political opponents murdered or imprisoned. To ordinary people, the president is a king; to titans of industry, he is a pawn. Given the work the Trump justices have done here, the billionaire class’ affection for Trump, often presented as counterintuitive, is not difficult to understand.

Yet when it comes to the justices’ decision on immunity, they were too clever by half. They seem to believe that when a president goes too far for their taste, they can declare he’s not immune and constrain him. But there is danger in a ruling that invites presidents to test the limits of their power. By the time a rogue president goes too far, he is unlikely to care what the Supreme Court says. A president unbound by the law is shackled only by the dictates of his own conscience, and a president without a conscience faces no restraint at all. And because they ruled as they did, when they did, and on behalf of a man lawless enough to try to overturn an election, Americans may pay for the justices’ hubris sooner rather than later.

Rather than leave such momentous decisions in the justices’ hands as they intended, the ruling empowers anyone amoral enough to commit crimes to do so without any fear of the law or the Supreme Court. The decision implies that this immunity would extend to anyone acting on the president’s orders—meaning that a president is free not only to commit crimes, but to turn the federal government itself into a criminal enterprise, one in which officials can act with impunity against the public they are meant to serve. That the executive branch has all the guns was true prior to the Court’s ruling. But until the justices had to find a way to keep Donald Trump out of prison for trying to stay in office after losing an election, few people believed that the presidency was as unbound from the law as the Supreme Court has now made it.

The American government was constructed with one basic idea in mind: that the three branches would prevent tyranny by counteracting one another. As Federalist No. 51 put it, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” But a subsequent clause is just as important: “What is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

The Framers were decidedly not angels—their acceptance of slavery being an obvious illustration of their fallibility. They understood that, to sustain itself, the structure of the government would have to account for vices as well as virtues. The Roberts Court’s ahistorical ruling reversed the entire purpose of the Constitution, from creating a government that did not need to be led by angels to creating one so imperial that only an angel ought to be allowed to govern it.

We could speculate on how presidents without fear of the law might act, but we already have a historical example in Trump’s favorite president, Andrew Jackson.

In 1831, the Supreme Court decided 5–1 in favor of a pair of missionaries who had been assisting the Cherokee in a dispute with the Georgia state government. The justices ruled that because the Cherokee constituted a sovereign nation, only the federal government had jurisdiction over them. Georgia had passed a series of laws authorizing the ethnic cleansing of the Cherokee from any lands claimed by the state, and as a result of the ruling, those laws had become invalid. But Jackson had no intention of upholding the Supreme Court’s decision and preventing Georgia from seizing those lands and displacing the Cherokee.

According to the Jackson biographer John Meacham, the president did not say, “Well, [Chief Justice] John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it,” the popular misquote of Jackson’s reaction. Instead he said, “The decision of the Supreme Court has fell still born, and they find that it cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate.” But the effect was the same. Neither Jackson nor the state of Georgia wanted to follow Marshall’s opinion, and so they ignored it. The federal government had already passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, so the decision would not have prevented the ethnic cleansing known as the Trail of Tears even had it been heeded. Nevertheless, the incident showed that the Supreme Court had no power to enforce its decisions; it relied on the good faith of the executive branch.

In the history of presidential crimes, the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans dwarfs anything Trump has done. Jackson acted as he did not because he believed the text of the Constitution granted him immunity, but because in 1831 the United States allowed only white men to vote and there was no constituency large enough to oppose his actions. In other words: He did it because he knew he could get away with it.

One could retort that the fact that the republic did not fall after a president ignored a Supreme Court decision should provide some comfort. Except that is not the lesson here. The lesson is that presidents and governments are capable of doing monstrous things to people they consider beneath them or to whom they are unaccountable. The extraconstitutional presidential immunity invented out of whole cloth by the Roberts Court offers to make presidents unaccountable not just to a portion of the people they govern, but to all of them.

Whatever crimes Trump has committed in the past, or chooses to commit in the future, he will, unlike Jackson, have the Supreme Court’s blessing—so long as he can disguise them as official acts. But even if Trump loses in November, this concept of presidential immunity conjured up by the Roberts Court has made the current crisis of American democracy perpetual. Until it is overturned, every president is a potential despot.

The Jackson incident is a well-known cautionary tale of presidential lawlessness. Trump’s entourage however, sees it differently—as inspiration.

Trump’s newly announced running mate, J. D. Vance, has said so himself. In 2022 , Vanity Fair reported that Vance had appeared on a podcast in which he said, “I think Trump is going to run again in 2024,” and added:

“I think that what Trump should do, if I was giving him one piece of advice: Fire every single midlevel bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state, replace them with our people.”

“And when the courts stop you,” he went on, “stand before the country, and say”—he quoted Andrew Jackson, giving a challenge to the entire constitutional order—“the chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.”

This is not a view of executive power that is going to submit to whatever legal technicalities the justices might use to restrain it, if they even wanted to. One likely reason Vance was picked is that, unlike former Vice President Mike Pence, Vance has openly said he would have tried to overturn the outcome of the 2020 election using the vice president’s ceremonial role in electoral-vote certification. In other words, he would be a willing accomplice to a coup. We might view Vance’s lawlessness here as a kind of audition for the next Trump administration, one he apparently aced.

The originalists of the Roberts Court, supposedly so committed to the text of the Constitution, the intent of the Framers, and the nuances of history, conjured out of nothing precisely the sort of executive office the Founders of the United States were trying to avoid. They did so because their primary mode of constitutional interpretation is a form of narcissism: Whatever the contemporary conservative movement wants must be what the Founders wanted, regardless of what the Founders actually said, did, or wrote.

The right-wing justices, in rewriting of the Constitution in Trump’s image, have clearly diverged from the intentions of the founders. In “Federalist No. 69,” Alexander Hamilton wrote that former presidents would “be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.” Expanding on his point, Hamilton wrote, “The person of the king of Great Britain is sacred and inviolable; there is no constitutional tribunal to which he is amenable; no punishment to which he can be subjected without involving the crisis of a national revolution.” The Roberts Court turned the office of the presidency the Founders made into the kind of monarchical office they rebelled against.

The justices, less independent arbiters than the shock troops of the conservative movement, wanted Trump to be immune to prosecution, and so they conjured a rationale for doing so, with a narrow window of legal accountability that only they have the right to determine. But that window might as well be barred from the inside: What Jackson’s story shows is that the feeble, arbitrary restraints the justices put into their own grant of royal immunity to Trump will not withstand any president with the capacity to violate them. Unfortunately, the day a rogue president shows the Supreme Court just how powerless it really is, it will not be the justices who suffer most for their folly.