The Lies Nostalgia Tells Us

9 min read

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

The current political climate is suffused with nostalgia for supposedly better times. I remember my own childhood, and those days weren’t better—but they had their sugary moments.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- All airlines are now the same.

- Voters aren’t sure who Kamala Harris really is.

- The Democrat who thinks Biden didn’t go far enough

Batman, Barnabas, and Bobby Kennedy

So much of our current national strife is predicated on how much better things were Back Then. For younger people, “back then” is the time they can barely remember, before Donald Trump began polluting our politics. For some people, it’s the years just before 9/11. Others have fond childhood memories of their first game system, in the 1990s, or their narrow ties and big hair from the ’80s. My generation—call us Gen Jones, wedged between the Boomers and the Xers—grew up in the late ’60s, a nice time to be a child but a period of frightening turmoil for anyone older than us.

(I have left out the ’70s. I graduated from high school in 1979; for me, the ’70s couldn’t end soon enough, and I doubt whether anyone is really nostalgic for them.)

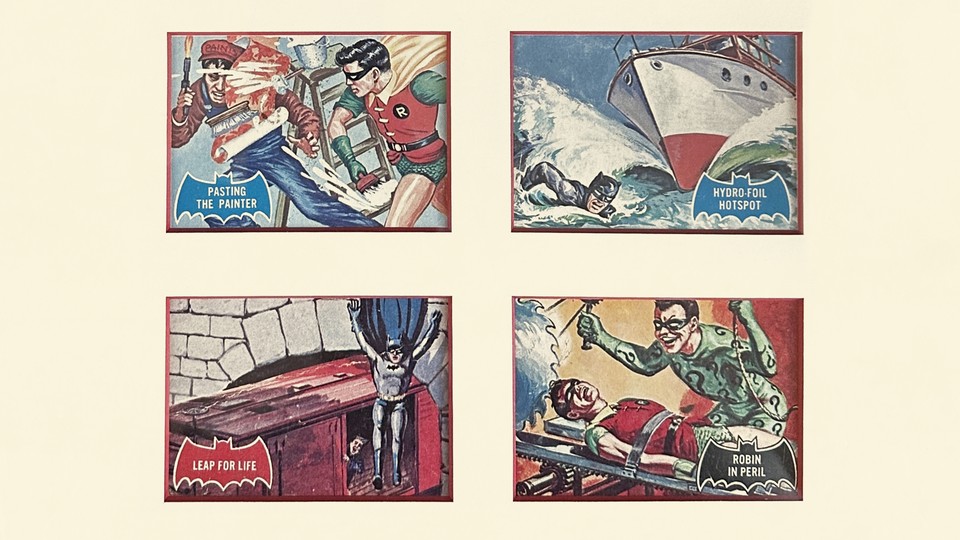

I was thinking about the prevalence of nostalgia recently while looking at a framed collection of some of my most treasured childhood possessions: the 1966 Batman trading cards issued by Topps. These were not scenes from the campy TV show, but comic-book art, and they are beautiful, whimsical, and just a little bit scary. (The Caped Crusaders fighting giant rats? The Boy Wonder screaming as the Riddler is about to saw him in half? Holy Inappropriate for Kids, Batman!)

Sports cards have always been big business, but starting in the 1950s, more trading cards based on TV shows, bands, fads, and big historical events began to appear. They usually sold for a nickel a pack, and they came with a stick of bubble gum. Well, I say “a stick of gum,” but in reality, it was more like a piece of thin plaster covered in powdered sugar, dusty stuff that made the cards smell sweet for years. Even “plaster” might not be a good description: Plaster, if made properly and chewed enough, is digestible.

Anyway, you chucked the stick and the wrapper and then waited to see which five cards you’d drawn. You prayed that you didn’t end up with dreaded “doubles,” because most of the cards had a piece of a puzzle on the back, and you needed to collect them all to see the finished picture.

Buying these cards was a cherished ritual of my childhood in Chicopee, Massachusetts. In my neighborhood, we had four possible places to go: three small stores and a pharmacy. Each week or so, new cards would arrive in the shops, and we would take our hard-earned money (sometimes from scavenging bottles for refunds) and make the rounds.

A man named Art Lapite ran one of these stores. He called all the boys “Butch,” and for as long as I knew him, he wore a kind of 1950s pharmacy smock. My dad used to go to Lapite’s to pay the utilities—as one could do back then—because he enjoyed the walk and liked to shoot the breeze for a moment or two. (I once tried to steal some stuff from there; Art quietly let me know that he was onto me and gave me a chance to put everything back and walk out. I did.)

We might also check the Red Store. (We didn’t know what its name was. It was red. Close enough.) But the mother lode was at Knightly’s Pharmacy, the local drugstore run by Mr. Knightly and his sisters. His candy rack, to my small eyes, was a majestic wall of God’s generous bounty. Finally, we’d arrive at Kane’s, a small market down by the riverbank. (That wasn’t its name, but again, that’s what we called it, and I can’t remember why.)

This odyssey would take us along a route that was classic small-town America. Chicopee Street included multiple gas stations: At the one owned by Mr. Ludwin, my family could just sign for gas. We would pass the American Legion post where my parents, both veterans, were members, and where my mom would sing on St. Patrick’s Day. You had your choice of three barbers; Dad and I went to the immigrant French Canadian guy. Our bicycles would zip past the local credit union (where I got my first bank account after starting a paper route). I did my homework at a branch library. Our little main drag also had at least three bars, some that would open early for the shift workers.

Mostly, our search for cards was a boy thing. The girls in our neighborhood weren’t big into Batman or the other TV shows and movies that showed up on the candy racks. (I still have a few cards from The Rat Patrol, a World War II drama; it was a hit on the Greek side of my family because it featured Christopher George, a Greek American actor).

One series, however, caught fire and united my neighborhood in an explosion of sugary pink smoke: Dark Shadows.

Dark Shadows was a boring Gothic soap opera until some genius at the ABC TV network said: Hey, what if one of the leads is a vampire? No, not the emotional kind, but a real, bloodsucking chieftain of the undead? A Canadian actor named Jonathan Frid was cast as the urbane and scary Barnabas Collins, and the show took off. Kids raced home from school to spend their afternoons getting weirded out. Soon, Dark Shadows trading cards were like child bearer bonds, gold in the hands of anyone who had them.

Things change. Now people apparently buy cards by the box just for the sake of owning them. At Walmart, you can snag a full set of basketball cards—14 boxes, seven packs a box, eight cards a pack, or 784 cards—for about $100. We couldn’t spend that kind of money, but why would we? We were scouring the town, pooling pennies, taking our chances, and then trading, which is why they were called “trading” cards. That’s what made them fun.

These are kind and gentle memories. But my collection also includes the cards issued by the Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation in 1968 after Robert F. Kennedy was shot.

You might think that an “assassinated politician” bubble-gum card is in bad taste, but strangely, I think it helped kids grasp what was going on. I lived in Massachusetts, and I knew that Bobby was Jack’s brother, but that was about it. I didn’t know who Martin Luther King was, but I knew he’d been murdered, and when I got the bubble-gum card that pictured RFK and MLK, I started to understand that good men were getting killed. I threw away a lot of cards, but I kept the one of Bobby and Martin.

When I look at those old cards, of course I feel a flood of nostalgia. Most of the landmarks of my childhood have crumbled or closed. A highway overpass destroyed the center of Chicopee Street. Lapite’s and Knightly’s are long gone. Kane’s is a check-cashing store. Most of the other businesses have disappeared (a few are now storefront churches), although the bars have held out longer—one of my high-school friends was stabbed to death in one of them, right next to my house, shortly after our class reunion almost 15 years ago.

When people look back and feel loss, I understand. But I am old enough now to know that these were not good days, and that the nostalgia is mostly a lie.

I remember Batman and Barnabas and Bobby. I also remember the alcoholism and drug abuse that plagued our neighborhood (and my family). I remember rampant domestic violence, although as children we didn’t know what to call it. I remember hospitals and nursing homes that now seem medieval to me. I remember air-conditioning being a luxury.

I remember the kids who were drafted; I remember others who I later learned were living miserable lives in the sexual closet. I remember people trudging to decrepit factories most Americans wouldn’t set foot in now. I remember being shooed away from fights between white kids from Chicopee and Hispanic kids from Holyoke, usually near the bridge over the Connecticut River that was like Checkpoint Charlie between our neighborhoods. (My church was only a short distance across that bridge; at 10 years old, I was held up next to it at knifepoint.)

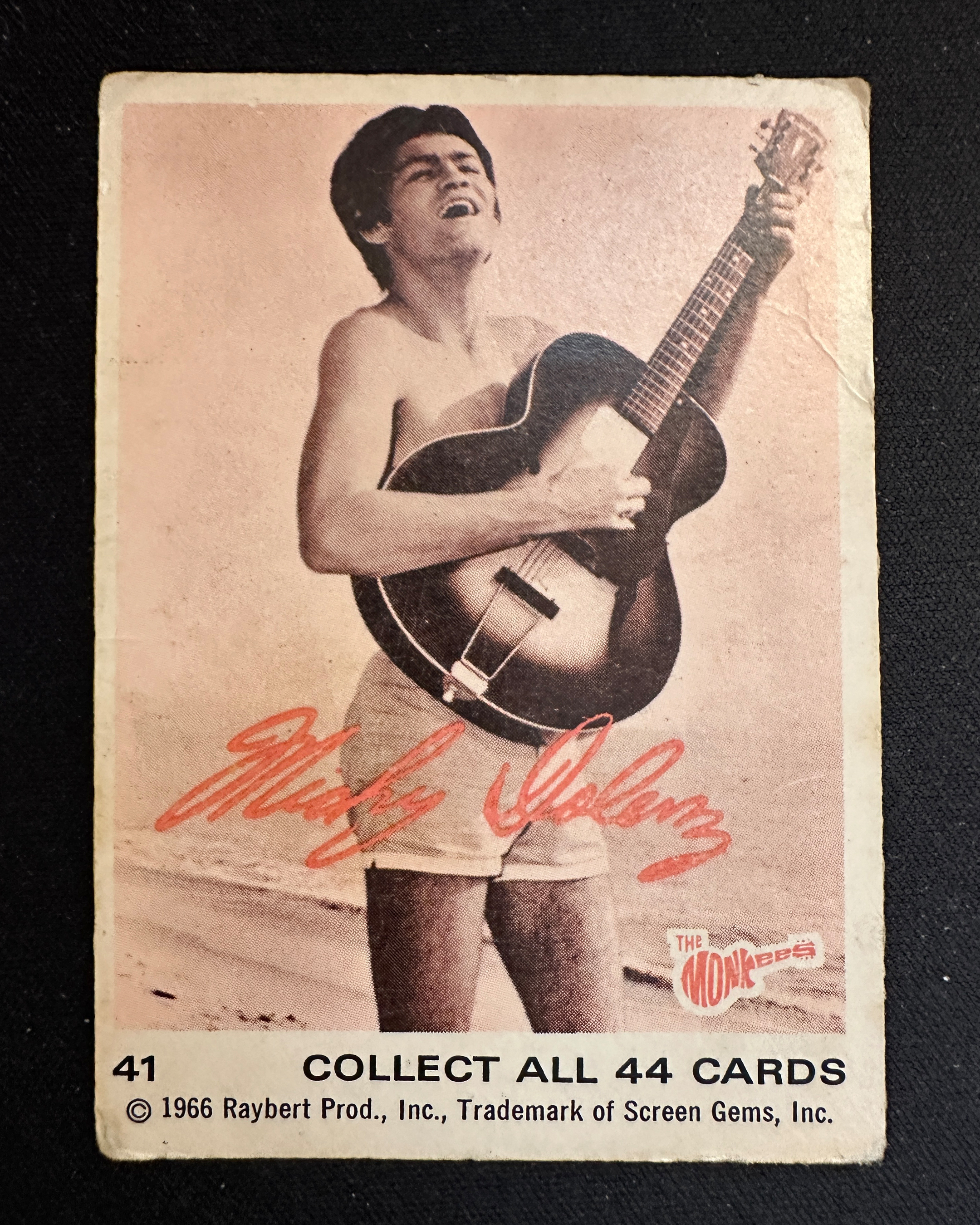

We can cherish our memories, but we should be clear-eyed about the past. I do not want those days back, and I will not support the vengeful authoritarians who sell such nostalgic rotgut. Nevertheless, I still smile at some of those favorite acquisitions of my childhood, including the cards I proudly bought in 1969 after the moon landing. I particularly like a card of Micky Dolenz of the Monkees, because I remember the crisp fall day I bought it from Art Lapite nearly six decades ago.

And when I posted a picture of the card on Twitter some years ago, Micky Dolenz thought it was cool too.

Related:

- How baseball cards got weird

- A cultural history of the baseball card

Today’s News

- Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu met with Donald Trump for the first time since Trump left the White House, in 2021.

- Arsonists set fire to parts of France’s high-speed-rail network this morning, ahead of the opening ceremony of the 2024 Summer Olympics, hosted in Paris.

- Barack Obama and Michelle Obama endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris for the Democratic nomination in the presidential race.

Dispatches

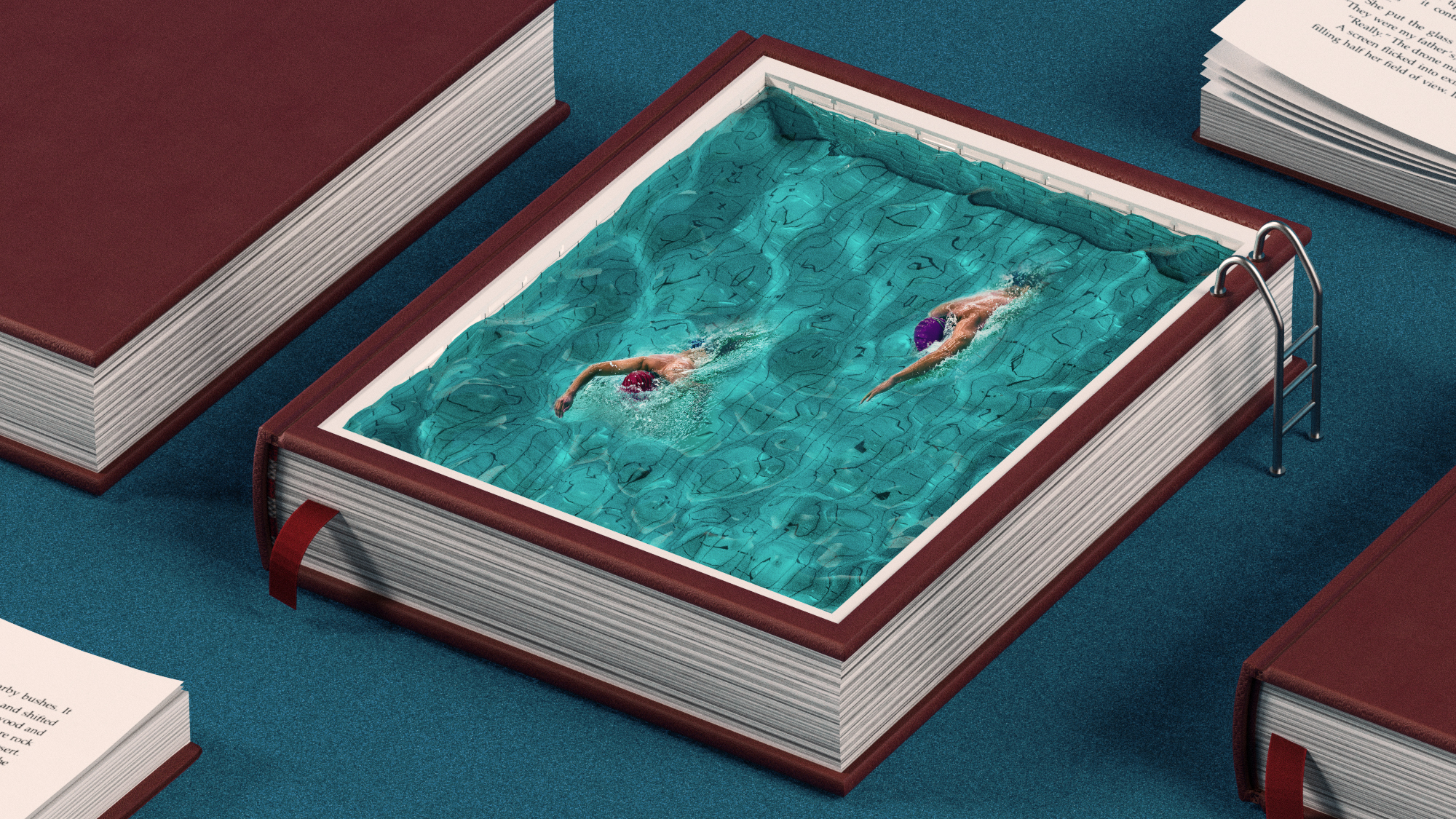

- The Books Briefing: These are the best books to read during the Olympics, Emma Sarappo writes.

- The Weekly Planet: Monday was characterized as the hottest day in 125,000 years, Zoë Schlanger writes. We’re just sticking a toe into the climatic realm of the previous interglacial period, not living in it—yet.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

Want to See a Snake Eat Its Tail?

By David Sims

Times change, corporate acquisitions happen, and now we have Deadpool & Wolverine, in which Deadpool not only knows he’s in a cinematic universe but also wants to go to a better one. It’s an almost entirely metatextual movie—a series of Variety articles given life, crammed in a Lycra suit and encouraged to curse with impunity. Shawn Levy’s film exists to properly usher Deadpool into Disney’s squeaky-clean Marvel Cinematic Universe, helped along by the wearily professional Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), dragged out of retirement (and death) for one last rodeo.

Read the full article.

More From The Atlantic

- This bad-vibes-TV moment needs to end.

- America’s political chaos is enviable when you live in an autocracy.

- Kamala doesn’t have to be “Momala” to the whole country.

Culture Break

Read. These seven books will change how you watch and understand the Olympics.

Watch.How to Come Alive With Norman Mailer (A Cautionary Tale), a documentary that offers a model for reassessing the lives of monstrous men, Gal Beckerman writes.

Play our daily crossword.

P.S.

A few years ago, I wrote a book titled Our Own Worst Enemy, in which I talked about the various threats to democracy that come from within democratic societies (and from within ourselves, if we are honest enough to admit it). In the summer of 2021, I took a drive back home to Chicopee with my daughter, Hope, a college student and budding videographer. I suggested, as a project, that she make an ad for the book.

My daughter had been back home with me only a few times as a small child, to see my father before he passed away. But she instinctively understood the sense of loss that I felt and that I was writing about, and she produced a video called Things Change, which my publisher was glad to use to promote the book. The video was shot mostly on Chicopee Street and near the riverbank where I played as a boy. You might find it interesting; you can watch it here.

— Tom

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.