This Is How Humans Find Alien Life on Mars

5 min read

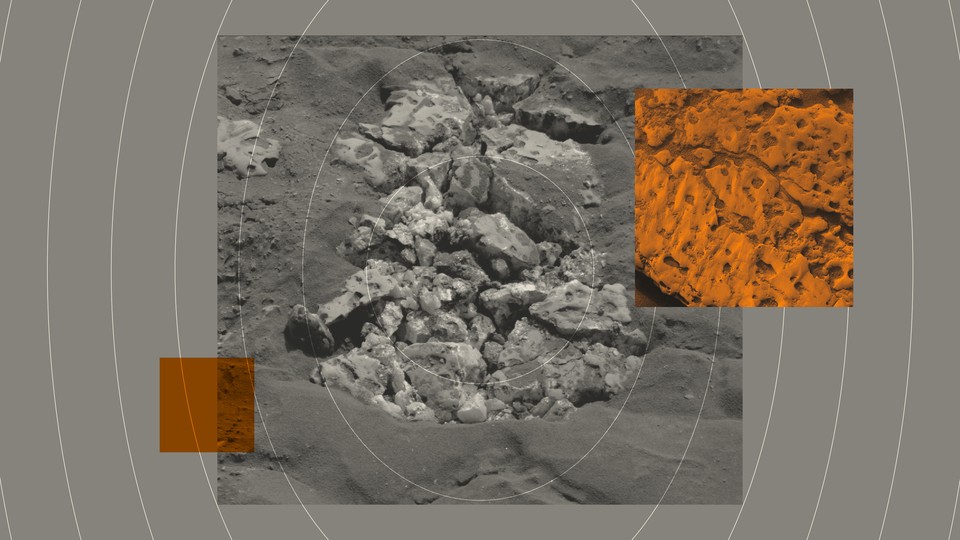

Yesterday, NASA announced that one of its Mars rovers had sampled a very, very intriguing rock. At first glance, the rock looks much like the rest of the red planet—rugged, sepia-toned, dry. But it’s arguably the most exciting one that robotic space explorers have ever come across. The rock, NASA said in a press release, “possesses qualities that fit the definition of a possible indicator of ancient life.”

Of course it would happen like this. In the midst of a historically eventful summer—an attempted assassination of a former president, the abrupt campaign exit of a sitting one, possibly the worst IT failure in history—scientists might have an alien discovery on their hands.

To be clear, the rock, which scientists are calling Cheyava Falls, bears only potential evidence of fossilized life. There are other plausible explanations for its appearance and composition, mundane ones that have nothing to do with biological processes. Still, scientists are thrilled. “This is the exact type of rock that we came to Mars to find,” Briony Horgan, a planetary scientist at Purdue University who led the selection of the mission’s destination, told me. But to really investigate whether Cheyava Falls contains marvelous, existential proof of another genesis in our very own solar system, NASA needs to bring the sample home—a prospect that might take more than 15 years.

According to NASA, the rover, called Perseverance, has detected in Cheyava Falls organic compounds, which are necessary for life as we know it. The rock bears dozens of leopard spots: tiny, irregularly shaped off-white splotches, ringed with black material that NASA scientists say contains iron and phosphate. Such features can arise from chemical reactions that could provide life-giving energy for microbes. If you encountered these leopard spots in an ancient rock formation on Earth, you would assume that some microscopic organisms once dwelled there.

The Cheyava Falls rock was found in a region of Mars’s Jezero Crater that many scientists believe flowed with water several billion years ago. Perhaps, before the planet froze over, there might have been enough time—and the right ingredients—for tiny life forms to emerge; if so, Jezero Crater could have been among the liveliest spots on the red planet. Cheyava Falls supports that theory because it is marked with streaks of calcium sulfate, which suggests that water once flowed through its sediments. Crucially, sulfate is good for preserving organic material, Horgan said.

Scientists inside and outside NASA know that the discovery comes with caveats. Carol Stoker, a NASA planetary scientist who is not involved in the mission, told me in an email that although “this is the most interesting rock that Perseverance has sampled,” she would like to see more evidence for the claim that the rover’s instruments detected organic materials. Entirely abiotic processes can produce organic compounds. And just because certain chemical components could serve as energy sources, that doesn’t mean that something once used them. “That’s like saying that a field of corn is evidence for the presence of cows,” Darby Dyar, a planetary geologist at Mount Holyoke College who has studied interactions between minerals and microbes, told me in an email.

More evidence isn’t likely to come anytime soon. NASA says that the Perseverance has studied the Cheyava Falls rock “from just about every angle imaginable,” with every instrument it’s got. But the rover alone can’t tell scientists if the discovery signals a true breakthrough. “The only way to be sure is to get that sample into a lab on Earth,” Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, told me in an email.

The good news is that NASA has spent years working on an ambitious mission, called Mars Sample Return, to do just that. The bad news is that the mission is currently in limbo. NASA officials put development on pause earlier this year, saying that the program had become too expensive and was taking too long. The working timeline meant that the samples that Perseverance has been collecting wouldn’t return to Earth until 2040, and even before the Cheyava Falls discovery, NASA wanted them back sooner. The agency is now considering alternative mission concepts, including bringing home fewer samples than planned. That possibility has worried scientists, and they’re no doubt hoping that the tantalizing finding persuades NASA not to give up on the mission. If nothing else, the timing of this discovery is convenient for proponents of sample return, an extra point of data in favor of bringing as many samples home as soon as possible.

Scientists are used to ambiguity in this line of work. Back in September 2020, in the throes of the coronavirus pandemic, scientists announced that they had found evidence of phosphine in the clouds of Venus—a gas that, on Earth, is associated with life. (Apparently there’s never a nice, quiet time to announce the discovery of maybe-aliens.) Almost four years later, scientists remain unsure about whether the phosphine is a product of living creatures, ordinary geological activity, or something else. To our knowledge, Venus remains lifeless.

Even if Cheyava Falls is brought to Earth, scientists might not come to any meaningful conclusions. They might not find anything because, as intriguing as Cheyava Falls looks now, Perseverance’s drill might have struck just to the left or the right of fossilized life, and none of it would have made it into the sample tube. Martian life might even be hidden in another part of the planet altogether, at its frigid poles or in underground caves. Or scientists could find nothing because they don’t know what to look for; their search is guided by the structure of life as we know it on Earth, and they may not recognize what our planetary neighbor has managed to create.

Short of the arrival of giant spaceships from an extraterrestrial civilization eager to bestow on us a new language, uncovering maybe-aliens in the form of teeny, long-dead microbes won’t change the course of most people’s daily lives. But the finding would still be a source of wonder, even comfort. It would mean that the history of life on Earth is just one story, perhaps one of countless others in the universe. A pale red dot, suspended in the same sunbeam as our blue one, with its own rich tale of movement and community. But until scientists can actually examine Cheyava Falls and other samples like it, we don’t have a hope of understanding how those stories might have begun.