‘Lord, Help Us Make America Great Again’

10 min read

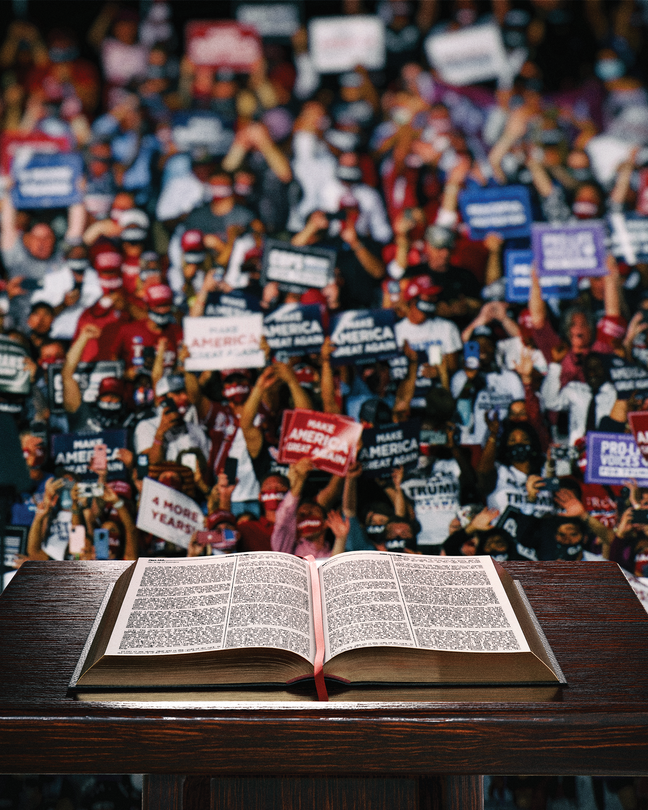

A week before Christmas, an evangelical minister named Paul Terry stood before thousands of Christians, their heads bowed, in Durham, New Hampshire, and pleaded with God for deliverance. The nation was in crisis, he told the Lord—racked with death and addiction, led by wicked men who “rule with imperial disdain.”

“With every passing day,” the minister said, “we slip farther and farther into George Orwell’s tyrannical dystopia.”

But because God is merciful, there was reason for hope. One man stood ready to redeem the country: Donald Trump. And he was about to come onstage. “We know what he did for us and how he strove to lead us in honorable ways during his term as our president—in ways that brought your blessings to us, rather than your reproach and judgment,” Terry prayed. “We know the hour is late. We know that time grows shorter for us to be saved and revived.” When he finished in the name of Jesus Christ, Amens echoed through the hall. Soon Trump appeared to rapturous applause and Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.”

For all the exhaustive coverage of Trump’s campaign rallies, even before the assassination attempt at one of them in July, relatively little attention has been paid to the prayers that start each one. These invocations aren’t broadcast live on cable news, nor do they typically attract the interest of journalists, who gravitate toward the more impious utterances of the candidate himself. But the prayers offered before Trump speaks illuminate this perilous moment in American politics just as well as anything he says from the podium. And they help explain how the stakes of this year’s election have come to feel so apocalyptically high.

To understand the evolving psychology and beliefs of Trump’s religious supporters, I attempted to review every prayer offered at his campaign events since he announced in November 2022 that he would run again. Working with a researcher, I compiled 58 in total, the most recent from June 2024. The resulting document—at just over 17,000 words—makes for a strange, revealing religious text: benign in some places, blasphemous in others; contradictory and poignant and frightening and sad and, perhaps most of all, begging for exegesis.

There are many ways to parse the text. You could compare the number of times Trump’s name is mentioned (87) versus Jesus Christ’s (61). You could break down the demographics of the people leading the prayers: 45 men and 13 women; overwhelmingly evangelical, with disproportionate representation from Pentecostalism, a charismatic branch of Christianity that emphasizes supernatural faith healing and speaking in tongues. One might also be tempted to catalog the most comically incendiary lines (“Oh Lord, our Lord, we want to be awake and not woke”). But the most interesting way to look at these prayers is to examine the theological motifs that run through them.

The scripture verse that’s cited most frequently in the prayers comes from 2 Chronicles. “If my people, who are called by my name, will humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and I will forgive their sin and will heal their land.”

Ryan Burge, a Baptist minister and political scientist I asked to review the prayers, told me that this verse—which is quoted 10 times—is regularly cited by evangelicals to advance a popular conservative-Christian narrative: that America, like ancient Israel before it, has broken its special covenant with God and is suffering the consequences. “The Old Testament prophets they’re quoting talk about sin collectively instead of individually—the nation has fallen into wickedness and needs healing,” Burge said. “The way they use this verse presupposes that we’re spiraling down the tubes.”

Trump’s supporters attribute America’s fall from grace to a variety of national sins old and new—prayer bans in public schools, illegal immigration, pro-transgender policies, the purported rigging of a certain recent election. Whatever the specifics, the picture of America they paint is almost universally—biblically—bleak.

In Wildwood, New Jersey, a pastor declared, “Our nation finds itself in turmoil, chaos, and dysfunction.” In Fort Dodge, Iowa, the sentiment was similar: “Lies, corruption, and propaganda are driving civilization to ruins.” In Conway, South Carolina, one supplicant informed God, “Our enemies are trying to steal, kill, and destroy our America, so we need you to intervene.”

The premise of all of these prayers is that America’s covenant can be reestablished, and its special place in God’s kingdom restored, if the nation repents and turns back to him. Burge told me that these ideas have long percolated on the religious right. What’s new is how many Christians now seem convinced that God has anointed a specific leader who, like those prophets of old, is prepared to defeat the forces of evil and redeem the country. And that leader is running for president.

Early on in the Trump era, it was common to hear conservative Christians compare him to Cyrus the Great, the sixth-century-B.C.E. Persian king who, though he did not worship the God of Israel himself, liberated the Israelites from Babylonian captivity and helped them build their temple in Jerusalem.

The subtext was not subtle. Here was a handy biblical precedent for the “unlikely vessel”—the man God uses to fulfill his purposes even though he lacks the faith and character of a true believer.

But this analogy seems to have outlived its usefulness to the religious right: A 2020 Pew Research Center survey found that 62 percent of Republicans viewed Trump as “morally upstanding,” and in a Deseret News poll commissioned last year, 64 percent said they believed he is a “person of faith.” The former president no longer needs to be described as a blunt, utilitarian tool in God’s hand. “Cyrus was a way of acknowledging, ‘I know this is an immoral person, but he could still do some good,’ ” Russell Moore, an evangelical theologian and the editor of Christianity Today, who has been critical of Trump, told me. “I haven’t heard Cyrus language in at least five years.”

The prayers at Trump’s rallies reflect this shifting perception. Cyrus isn’t mentioned, but Trump does get compared to righteous, prophetic heroes of the Bible, including Esther, Solomon, and David.

In America, more than perhaps anywhere else in the Western world, petitions to God are still a routine fixture of politics—at congressional sessions, presidential nominating conventions, inaugurations. After a gunman shot at Trump during a rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, in July, both Democrats and Republicans prayed for the former president and for the country he hopes to lead.

And many presidential campaigns are infused with religion. In July, Joe Biden attended a church service in Philadelphia where the pastor compared the president’s recent political struggles to the Old Testament story of Joseph, and a member of the congregation prayed for Biden: “Touch his mind, O God, his body; rejuvenate him and his spirit.”

Bradley Onishi, a scholar and former evangelical minister who studies the intersection of politics and Christianity in America, told me that prayers at political events have traditionally fit a certain mold. God is asked to grant the political leader inspiration and wisdom, to help him resist temptation and lead the country in a righteous direction. “It was always ‘We pray for him to have the strength to do God’s will, to have character, to be the man we need,’ ” Onishi said.

Some of the prayers at Trump’s rallies run along these lines, and would be familiar to anyone who has spent time in an American church, myself included. “Give President Trump the strength to make the right decisions both in and out of the public eye,” one man prayed at a Trump event in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. “Remind him to seek your guidance as events unfold.” I have said “Amen” to a thousand prayers like this in my life, on behalf of government leaders in both parties.

But Onishi, like several of the other experts I asked to read the prayers, was struck by how many of them take Trump’s righteousness for granted. “No one prays for Trump to do right; they pray that God will do right by Trump,” Onishi told me.

Indeed, rather than asking God to make Trump an instrument of his will, most of the prayers start from the assumption that he already is. Accordingly, many of them drop any pretense of thy-will-be-done nonpartisanship, and ask explicitly for Trump’s reelection. “Lord, you have a servant in Donald J. Trump, who can lead our nation,” a woman offering a prayer in Laconia, New Hampshire, told God at a rally on the eve of the state’s Republican primary. “Help us to overcome any obstacles tomorrow so that we may deliver victory to your warrior.”

With Trump’s goodness presumed, the criminal charges against him are cast not as evidence of potential wrongdoing but as a sign of victimhood. “We ask that you put a hedge of protection around President Trump,” one woman prayed in Waukesha, Wisconsin, “and deliver him from the baseless attacks, and remove from office those who are subverting justice in our legal system.”

At a Februarycampaign event in North Charleston, South Carolina, Mark Burns, a televangelist in a three-piece suit, squeezed his eyes shut and lifted his right hand toward heaven. “Let us pray, because we’re fighting a demonic force,” he shouted. “We’re fighting the real enemy that comes from the gates of hell, led by one of its leaders called Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.”

Although Burns was more provocative than most, he was not alone in using the language of spiritual warfare. This is perhaps the most unnerving theme in the prayers at Trump’s rallies. One verse, from Ephesians, is quoted repeatedly: “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

Russell Moore told me he used to hear conservative evangelicals cite this verse as a way of shifting the focus away from earthly concerns like politics and toward the larger, more important battle for our souls. “The point would be that our opponents aren’t our enemies,” he told me. But something has changed in recent years. “That’s not the implication I see in these prayers. It’s ‘Politics is how we fight these spiritual battles.’ ”

Terry Amann, a conservative pastor in Iowa, told me I shouldn’t be surprised to hear such a dire framing of the election. Christians like him see abortion as a grave sin and fast-changing social mores around gender and sexuality as serious threats to the nation’s spiritual health. “Every election cycle, they say this is the most important election in your lifetime,” he told me. To him, it feels like this one really is. “Our republic is in trouble.”

But it’s easy to see the danger in internalizing the concept of politics as spiritual combat. Trump’s rallies become more than mere campaign events—they are staging grounds in a supernatural conflict that pits literal angels against literal demons for the soul of the nation. Marinate enough in these ideas, and the consequences of defeat start to feel existential. “This is not a time for politics as usual,” a Pentecostal preacher declared at a Trump rally in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, last year. “It’s not a time for religion as usual. It’s not a time for prayers as usual. This is a time for spiritual warriors to arise and to shake the heavens.”

As I was reviewing these prayers, I wondered what Trump’s most zealous religious supporters would do if they didn’t get the result they were praying for in November. With so much riding on the idea that Trump’s reelection has a divine mandate, what would happen if he lost? A destabilizing crisis of faith? Another widespread rejection of the election’s outcome? Further spasms of political violence?

It wasn’t until I came across a prayer delivered in December in Coralville, Iowa, that a more urgent question occurred to me: What will they do if their prayers are answered?

Onstage, Joel Tenney, a 27-year-old evangelist with a shiny coif of blond hair and a quavering preacher’s cadence, preceded his prayer with a short sermon for the gathered crowd of Trump supporters. “We have witnessed a sitting president weaponize the entire legal system to try and steal an election and imprison his leading opponent, Donald Trump, despite committing no crime,” Tenney began. “The corruption in Washington is a natural reflection of the spiritual state of our nation.”

For the next several minutes, Tenney hit all the familiar notes: He quoted from 2 Chronicles and Ephesians, and reminded the audience of the eternal consequences of 2024. Then he issued a warning to those who would stand in the way of God’s will being done on Election Day.

“Be afraid,” Tenney said. “For rulers do not bear the sword for no reason. They are God’s servants of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer. And when Donald Trump becomes the 47th president of the United States, there will be retribution against all those who have promoted evil in this country.”

With that, he invited the audience to remove their hats, and turned his voice to God. “Lord, help us make America great again,” he prayed.

This article appears in the September 2024 print edition with the headline “‘Lord, Help Us Make America Great Again.’”