The Sweet Spot for Anxiety

6 min read

Imagine that you just got a bad job evaluation, or learned that your suspicious mole really might be cancer. Your heart races, your chest tightens, your mouth is cottony dry and your skin damp with sweat—all classic physical symptoms of anxiety. Unless you’re one of the Alex Honnolds of the world, the sensation of anxiety is just about universal.

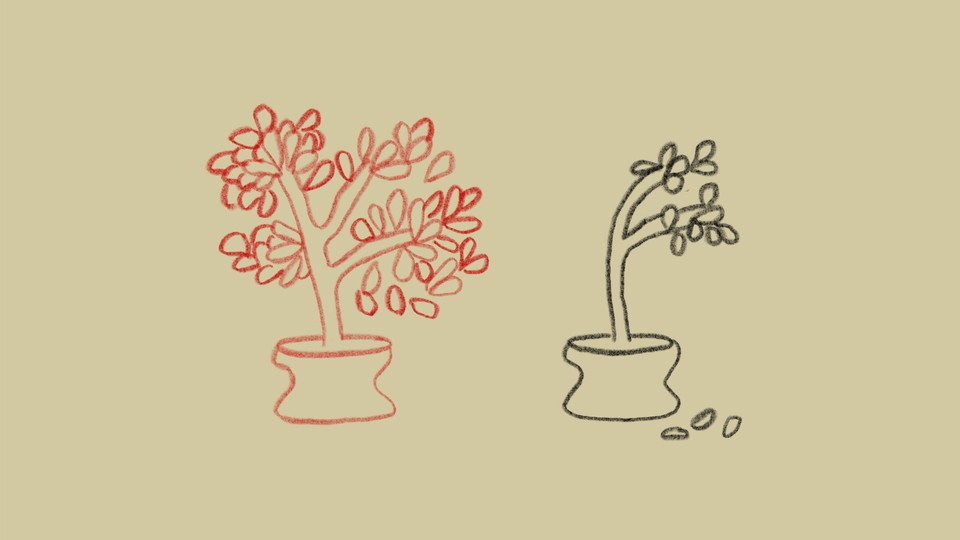

But the human body’s consistent response to anxiety actually masks two different psychological (and biological) phenomena. The first—let’s call it “growth anxiety”—occurs in response to challenges that are uncomfortable but manageable. The second—call it “toxic anxiety”—arises from situations that exceed one’s ability to cope. It’s the difference between finding a leak in your basement and losing your house in a hurricane.

Growth and toxic anxiety have markedly different effects on our brain and body. Over the past decade, anxiety of any sort has developed a reputation for ruining health. Americans of all stripes are going out of their way to escape it through medication or lifestyles that promote tranquility. And in fact, toxic anxiety can be biologically and psychologically harmful. But growth anxiety can promote health and resilience, much in the way that physical exercise can make us fitter.

The key characteristic of growth anxiety is that, although it might feel uncomfortable, it doesn’t exceed one’s ability to adapt. In general, one’s performance under pressure follows an inverted-U function: As stress goes up, performance rises to a peak, then drops off. This relationship, called the Yerkes-Dodson Law, was first described in 1908. Since then, dozens of studies have shown that there is an optimum level of stress that can produce, say, the best boardroom speeches and baseball hits. Those white-collar professionals and baseball players may not recognize it, but this is growth anxiety’s sweet spot.

When I was the director of student mental health at Weill Cornell Medical College, I frequently saw students who sought relief from anxiety in the face of intense academic demands. One first-year student told me he’d never worked so hard in his life but was still worried that he couldn’t cut it. He wanted me to medicate those concerns away. As I talked with him, though, I learned that he was succeeding academically, if not crushing his exams. He was stressed, yes, but handling his situation well, not sliding down the inverted-U curve toward overwhelming distress and failure. He had been a competitive runner, so I asked him how he’d felt when racing. Nervous, he told me, and a little sick to his stomach. Just as he felt before high-stakes exams, I pointed out. He got it instantly. Learning that his anxiety was a normal response to a new challenge, not a sign of a psychiatric disorder that needed treatment, was a great relief to him.

The remarkable thing about growth anxiety is that it can foster resilience in mind and body alike. Evidence from both animals and humans suggests that the experience of controllable stress—compared with either uncontrollable stress or even no stress—can protect an individual against the negative effects of both current and future stresses. That’s likely because acute anxiety triggers a brief surge in two stress hormones: cortisol and norepinephrine. Cortisol prompts the body to release glucose for energy and amp up immune function. Meanwhile, norepinephrine, a close relative of adrenaline, increases your heart rate and blood pressure, preparing you for flight or fight, and makes you laser-focused. That’s why stimulants such as Adderall and Ritalin, which increase norepinephrine more powerfully than everyday anxiety, have powerful energizing effects.

Just about everyone knows from experience that walking around with your heart pounding, ready to throw a punch at the first threat you see, can feel uncomfortable in the moment. But as long as those effects don’t last too long, they can be seriously beneficial. A short pulse of cortisol, in combination with other physiological responses to acute stress, can strengthen the connections between neurons in the hippocampus, a brain region that is essential to memory and learning. And evidence from stressed-out rodents and humans suggests that brief exposure to cortisol can prevent the emergence of anxiety-like or PTSD-like behaviors.

By contrast, chronic stress and the anxiety it produces are neither healthy nor advantageous. Persistent elevation of cortisol and norepinephrine can increase one’s chances of developing diabetes, obesity, and hypertension while impairing cognitive function. Whereas a short-term challenge can cause neurons in the hippocampus to grow, chronic exposure to cortisol can shrink them. In a 2009 study, researchers followed 20 healthy medical students during the month they studied for a major exam—a period in which they experienced near-constant stress. The researchers found that the students in the high-stress exam group were slower on a test of cognitive flexibility and had less functional connectivity in their prefrontal cortex (the brain’s reasoner in chief) than control subjects did. When the students were reassessed a month after they had taken the exam, those adverse effects had resolved.

Stress in response to an ongoing threat is one form of toxic anxiety; another occurs in people who find themselves highly distressed in situations that pose them little or no threat, such as those with social-anxiety disorder or generalized-anxiety disorder. Those with such hypersensitive threat detection probably had a leg up in a Paleolithic world full of menace, but in a modern one, such stress is usually maladaptive—except in the rare cases when modern life presents true menace, which many people underreact to. On 9/11, a former patient of mine with generalized-anxiety disorder was in his office in the South Tower of the World Trade Center. After the North Tower was hit, announcements rang through the second tower, telling people that it was safer to stay in the building. Even after an evacuation was ordered, many people delayed their exit. But my patient, who was predisposed to worry and catastrophic thinking, ignored the first announcement and fled minutes before the tower was hit. His anxiety disorder, which had previously made him miserable, saved his life.

Sometimes, toxic anxiety is unavoidable. Certain work environments and relationships can cause unrelenting, harmful stress; in these cases, the fix may require finding a different job or partner. And people with severe anxiety in the absence of any stressor can benefit from professional evaluation for the treatment of a likely anxiety disorder.

For most people, however, turning toxic anxiety into growth anxiety is within your power. Another patient of mine recently had a series of health problems that made him feel inundated and panicky. He was chronically worried and socially isolated. He felt defeated, gave up on his diet and exercise routine, and avoided any follow-up appointments with his internist for prediabetes. Together, my patient and I broke down his cascading problems into challenges with manageable solutions. First, we chose the quickest plan of action with immediate results: cataract surgery. Then we identified doable long-term interventions, such as modestly increasing his activity level and introducing healthier foods. Before long, he felt a sense of control, and his sense of being overwhelmed disappeared.

Each of us has a different sensitivity to stress. The same challenge, such as giving a public presentation, could be terrifying for one person and exciting for another. But no matter your stress tolerance, even small interventions—like getting sufficient sleep and exercise—can help prevent you from sliding down the inverted-U curve. We shouldn’t fear growth anxiety any more than we do the soreness that comes with a healthy workout. Both can be uncomfortable but make us stronger in the long run.