Venezuela’s Dictator Can’t Even Lie Well

8 min read

As we were speaking, Leopoldo López’s telephone kept buzzing. The national director of his political movement, Voluntad Popular, had just been arrested in Caracas. López had spoken to Freddy Superlano earlier in the morning. “I know they are coming for me, but I’m not scared,” Superlano had told him. Well, López had responded, “prison is not the end of the world.”

López knows about Venezuelan prisons because he spent more than three years in them; three years of house arrest followed. The charges were trumped up. His real crime was first to be elected mayor of Chacao, a part of Caracas; then to become one of Venezuela’s most popular opposition leaders; then to be a leader of mass protests. He finally escaped the country in 2020 and now lives mostly in Spain. But he was in Washington yesterday, two days after Sunday’s dramatic Venezuelan presidential election, and we had a chance to speak.

The conversation took place at an extraordinary, almost giddy moment. In the hours after the polls closed, much of the international media had refrained from stating the obvious. “BREAKING:,” the Associated Press tweeted on Monday. “Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro is declared the winner in the presidential election amid opposition claims of irregularities.” But by Tuesday morning, it was absolutely clear that the election was not merely irregular or tainted or disputed: The election had been stolen.

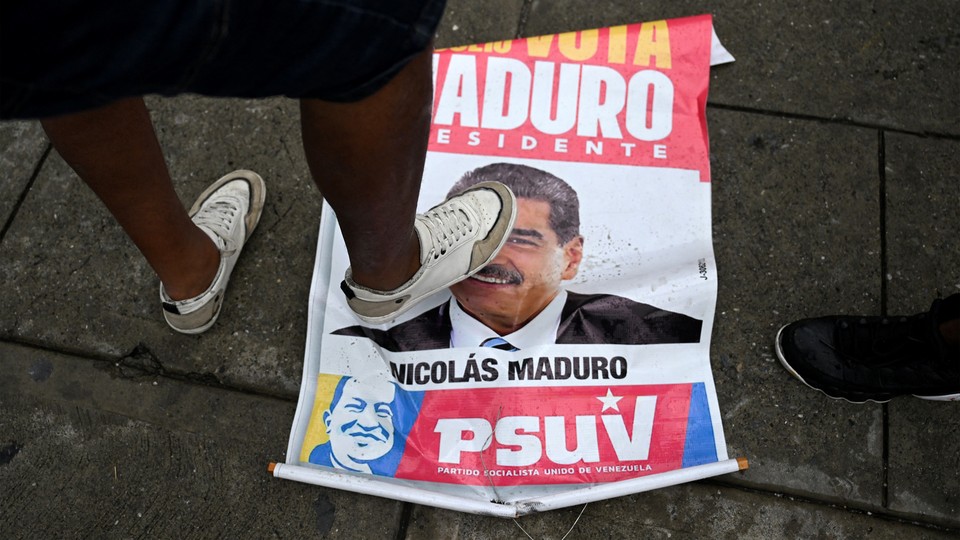

The reaction was immediate. Not just marches, not just protests, but assaults on the symbols of the regime, including monuments to Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez. “All throughout the country,” López said, “people are tearing down the statues of Chávez. And it’s not just the fact that they are tearing down the statues, it’s the way in which they’re tearing them down—like after the fall of the communist regimes in 1989, we are seeing massive emotional engagement with this. I cannot tell you if it’s going to be days or weeks, but I believe that we are witnessing the end of the dictatorship.”

How do they know that Maduro had truly lost the vote? Because organizers of Venezuela’s democratic opposition—thousands of people inside and outside of the country—painstakingly prepared for this election, assumed it could be stolen, kept track of multiple legal violations and violent attacks from the regime, and stayed united anyway. More than 2 million people from different opposition parties participated in a joint presidential primary and selected a candidate, María Corina Machado, a politician who has been active for more than two decades and is well known for her belief that the regime requires fundamental change. When Maduro arbitrarily barred her from running, the coalition switched to Edmundo González, a little-known former ambassador—and united behind him too.

Throughout the campaign, González supporters and other political leaders were assaulted, arrested, and detained by the National Guard as well as by armed civilian groups. Government thugs wrote threatening graffiti on campaign offices as well as university buildings, radio stations, union halls, and the homes of some activists. Official media overwhelmingly supported Maduro and smeared his opponents. Once the richest country in South America, Venezuela is now, after more than two decades of misrule, one of the poorest, and the regime uses food rationing to influence political behavior too.

Nevertheless, independent polls taken throughout the campaign repeatedly showed González with a large lead. On voting day, Edison Research, a U.S. based company, conducted an exit poll, commissioned by a private company. The result showed a landslide: 65 percent for González, 31 percent for Maduro, with González leading among old, young, male, female, urban, rural, and suburban voters. AltaVista, a parallel-vote-tabulation initiative—a project aimed at tracking votes in case the regime cheats—also produced an estimate of the national vote using methodology that organizers had explained in advance, posting it at the Open Science Foundation website. On the day of the election AltaVista obtained real results from about a thousand polling stations, photographed them, analyzed them and then sent the results around the world. They also showed a landslide: 66 percent for González, 31 percent for Maduro. By Monday evening Machado announced that her team had received voter tallies from more than 70 percent of the country’s precincts. The result, again, was a landslide for González.

This painstaking collection of evidence Sunday, along with the months of preparation needed to produce it, contrasts sharply with the sloppiness of the regime, which has so far not produced a full set of electoral statistics. Instead, Maduro has made ludicrous claims of victory and accused López and Machado, among others, of having hacked the results from a mysterious location in North Macedonia—an explanation that even the most fanatical loyalist must find hard to believe. The contrast between the two sides is impossible to obfuscate or deny: On one side people are defying violence and arrest to reform their country, reverse its downward slide, stop the tide of emigration. On the other side is a slovenly dictator who can’t even compose an intelligible lie.

The sudden, dramatic revelation of both the regime’s unpopularity and its incompetence have created a situation Venezuela’s neighbors cannot ignore. The left-leaning leaders of Colombia, Chile and especially Brazil—whose president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, was once chummy with Chávez—have asked to see the real electoral results too. López told me that defections are occurring within the Maduro regime: “We’re seeing police officers taking uniforms off and joining the protest. We’re seeing the National Guard deciding not to follow the orders of repression.” In Venezuela, the military is deployed in polling stations, “so they saw what happened. They saw who voted for who.” Commanders will have to make a choice: “They could, at this stage, still be part of a good story. They can side with the people, side with the election, side with the Constitution, side with the international community, and be part of the transition.”

López thinks Maduro himself will cling to power as long as possible. “But other people might make a different choice,” especially given the combination of events. “It’s the elections, the protests, the international pressure, the defections. We’ve seen all of that before, but isolated one from the other. Now it’s a perfect storm. It’s all of this happening simultaneously.”

Clearly, the regime did not anticipate this outcome when the voting was planned. Roberto Patiño, another Venezuelan activist whom I spoke to by telephone, told me that Maduro was “arrogant and out of touch” and simply took it for granted that he would win. López too reckons Maduro miscalculated: “He thought by disqualifying Machado, that it would be impossible to find an alternative candidate. But we did,” López said. Other attempts to manipulate the result, even to create a fake opposition, also failed. “I think he miscalculated the people, misunderstood the sentiment for change. I think he thought he was going to regain legitimacy with the election. Dictators make mistakes.”

Although the protests will be the most visible sign of unrest, the most momentous decisions over the next few days will be made by insiders. Lopez told me that he believes two sets of negotiations are going to unfold. “There will be one between Maduro and the military, and I think what we could see is the military just knocking on the door of Maduro and saying, you know, this is it.” If that were to succeed, there would then have to be “a negotiation between whoever is in charge and the democratic movement and the international community, in order to agree on the terms of this transition.” As for the fate of the incumbent himself, López doesn’t care. “The priority at this moment is not what will happen to Maduro. The priority is to transition to democracy.”

López is not alone. Last week, Patiño suggested in an article in The New York Times, that the U.S. administration could help Maduro leave the country. Others are hoping that President Lula plays that role. Maybe Maduro would move to Cuba, the regime’s closest ally? López laughed. “I don’t think he’ll choose Cuba. I think he’ll choose Qatar or Turkey. I mean, he loves luxury, and his wife loves luxury, and so I don’t think they’ll go to a run-down country like Cuba, although that’s been the model of the Promised Land, first for Chávez and now Maduro.”

Plenty of obstacles still stand in the way of a transition, which can still be derailed. Maduro might try to wait out the protests, to hold on to power until everyone gets tired. He might unleash an even more intense wave of violence. The network of autocracies that have kept first Chávez and then Maduro afloat for so long might do so again. “Yeah, no surprise, what we saw is a quick response and support for the false result from China, Russia, Iran, Cuba, and other autocracies,” López said. “They have a lot at stake in Venezuela in different ways. The Iranians are involved with business and energy. The Russians are involved with the military and the kleptocratic network. The Chinese offer financial support to Maduro.” López thinks the weapons, cash, and diplomatic support they can provide are no longer relevant. “At this moment, it’s about the people and the rage of the people to defend their results of the election.”

The sudden sense of hope, possibility, and optimism that López radiated amid all this is difficult to capture in words. We in the democratic world take regular, orderly political change for granted. In Venezuela, millions of people have worked for years to get to this moment, just to experience a moment when change might be possible. López first ran for office in 2000. Machado was a candidate for president the first time back in 2012. Since then, the destruction of the Venezuelan economy has accelerated; the mass exodus of Venezuelans has increased; the hopelessness and cynicism have deepened. Just a tiny shaft of light is enough to cheer even people who gave up long ago.

We talked for a few minutes longer, about what he might do next, who he was seeing in Washington (answer: everyone he can). Then he had to go. His phone was buzzing again, even more insistently. López has been fighting for democratic change in Venezuela for a quarter century, and a lot of people want to talk to him this week.