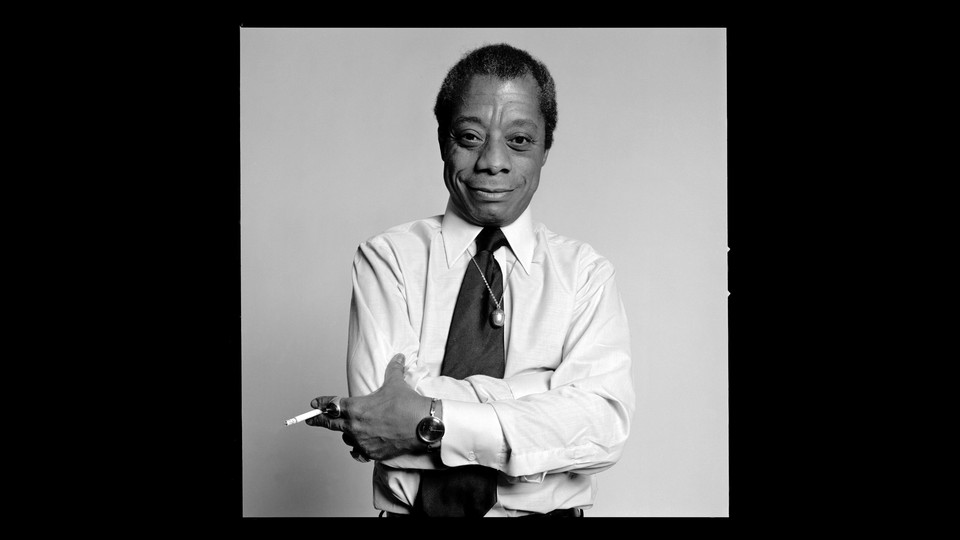

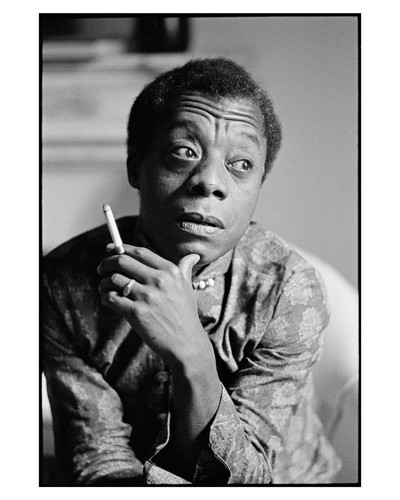

James Baldwin’s Most Underappreciated Talent

5 min read

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

James Baldwin—the playwright, activist, orator, and novelist—was born 100 years ago today. It is no fringe opinion that his work changed American letters forever. (Earlier this year, for example, The Atlantic named Giovanni’s Room one of the greatest American novels of the past century.) Today, Vann R. Newkirk II wrote about one talent of Baldwin’s that is largely overlooked: letter-writing. His correspondence was “actually the form where his light shone brightest,” Newkirk argues.

Most of Baldwin’s letters are kept in New York City’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. But, if you can’t make the trip to Harlem, where Newkirk read many of Baldwin’s exchanges, you can view a large number of items associated with the author’s life without traveling anywhere. A great place to start is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. The Smithsonian overall has invested dramatically in digital accessibility under the leadership of Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III, and letters, notes, and papers from the James Baldwin Collection are available online.

As Newkirk observes, many letters that friends and acquaintances sent to Baldwin begin with “Dear Jimmy,” revealing a man who “was approachable … even as he prompted a deep sense of respect.” Indeed, people who had never before written to him felt “a certain familiarity”; one letter from the NMAAHC collection especially proves this point. “Dear James: Please excuse me for taking the p[r]erogative of addressing you by your first name, but I feel just that close to you,” Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in 1961, after reading Baldwin’s essay collection Nobody Knows My Name. Baldwin was in touch with Lena Horne, Nina Simone, and Ray Charles; Toni Morrison, Lorraine Hansberry, and Maya Angelou. He wrote impassioned open letters in support of the feminist activist Angela Davis and against the policies of incoming Vice President Nelson Rockefeller. And, of course, he wrote the famous epistolary work The Fire Next Time, addressed in part to his nephew.

Personally, the papers that struck me most were a few draft pages of an essay written for Playboy magazine. These are not quite personal correspondence: Baldwin’s words are meant for the public, but they appear here in an unfinished version, with proofreading marks and comments left for his review. Baldwin is writing about the development of his play Blues for Mister Charlie, loosely inspired by the murder of Emmett Till. As he considers society’s collective responsibility for children’s welfare, he makes it clear that his aim is high: “We must make the great effort to realize that there is no such thing as a Negro problem—but simply a menaced boy. If we could do this, we could save this country, we could save the world.” That echoes something Newkirk notices in Baldwin’s writing: He “believed in the power of the word to change the world.”

But even Baldwin, who wielded language so influentially that we’re celebrating him a century later, was still, first and foremost, a person. Yes, his fans wrote him letters telling him how he’d changed their lives, but his editor left him corrections and marginal notes like “? explain,” and his friends sent messages from afar about how they missed him. These papers and letters are a testament to the power of his many connections with other people, Newkirk writes, and prove above all that Baldwin had “a genuine love for humanity.”

The Brilliance in James Baldwin’s Letters

By Vann R. Newkirk II

The famous author, who would have been 100 years old today, was best known for his novels and essays. But correspondence was where his light shone brightest.

Read the full article.

What to Read

Native Son, by Richard Wright

When this novel was published, in 1940, it shocked readers with its rawness and honesty, and it became an instant literary classic. Bigger Thomas is a Black man living on the bleak, poverty-stricken South Side of Chicago. When he gains access to a richer, whiter Chicago by way of a live-in job in the mansion of a real-estate magnate, his world expands and simultaneously becomes filled with menace. One wrong move leads to the next in a fatalistic chain of events. Bigger’s harrowing story is a bit like Lily Bart’s downward spiral in The House of Mirth, but in this case, it becomes a stinging indictment of American racism. Although James Baldwin famously criticized Wright’s novel for relying on stereotypes, he also acknowledged its power, writing, “No American negro exists who does not have his private Bigger Thomas living in his skull.” This may be the darkest of these city novels, depicting an untamed, Depression-era Chicago rife with division, violence, and hypocrisy. Bigger is punished, Wright suggests, because he dares to challenge his city’s implicit rules about where he belongs. — Pamela Newton

From our list: Eight novels that truly capture city life

Out Next Week

📚 The Pairing, by Casey McQuiston

📚 And So I Roar, by Abi Daré

📚 I Am on the Hit List: A Journalist’s Murder and the Rise of Autocracy in India, by Rollo Romig

Your Weekend Read

The ‘Grandma Gymnast’ Is Here to Stay

By Kelly Jones

In the past decade, interest in adult gymnastics has exploded, coinciding with the growing age of champions around the world. For years, successful female gymnasts traditionally peaked at 15 or 16 years old. Many trained under abusive conditions. They competed for their coaches or their countries, not themselves. But now gymnastics is dominated by women in their mid- to late 20s (and even early 30s) who want to win on their own terms. Their longevity is inspiring more grown-ups, both amateur and professional, to return to the sport—and encouraging others, who might never have thought gymnastics would welcome them, to learn to flip too.

Read the full article.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Explore all of our newsletters.