M. Night Shyamalan’s Most Unserious Movie Yet

4 min read

Midway through M. Night Shyamalan’s latest thriller, Trap, a young girl is chosen to dance onstage with her idol, a singer who goes by “Lady Raven” (played by the director’s daughter Saleka). The lucky attendee is understandably nervous, but a stage manager tells her not to overthink it. “It’s not about being good,” she advises. “It’s about having fun!”

The line doubles as guidance for viewers, many of whom will have ideas about what to expect from Shyamalan: a horror film with a pivotal plot twist that will chill them (The Sixth Sense), confuse them (Lady in the Water), or make them laugh at the absurdity (The Village). But Trap, more often than not, encourages its audience to laugh with it. Shyamalan pitched the story as “if TheSilence of the Lambs happened at a Taylor Swift concert,” a terrifying premise that also sounds like a twisted joke, something more likely to happen in a Batman comic than in real life. Trap is, as such, sillier than it is scary, the story shapeshifting in ways equally sinister and loony—which seems to be the point. The film doesn’t intend to be “good”; it wants its viewers to have some delirious fun.

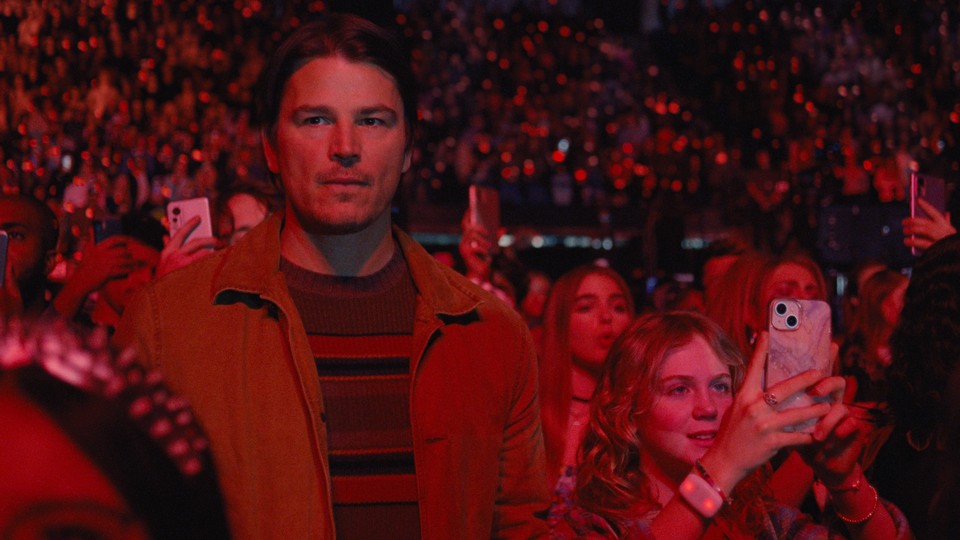

That it works at all is due in large part to Josh Hartnett, an actor who’s enjoying something of a career renaissance after his work in last year’s Oppenheimer. Here, Hartnett stars as Cooper, a father taking his daughter, Riley (Ariel Donoghue), to the Lady Raven concert, but who also turns out to be—and this is only a surprise if you’ve avoided every single trailer—a serial killer known as “The Butcher.” The concert is doubling as an elaborate ruse by the authorities to catch Cooper, who must find a way to escape without raising any suspicions, most of all from Riley. Hartnett is a thrill to watch as Cooper slips between his dual personas from scene to scene, awkwardly bonding with Riley in one moment and fooling SWAT teams with practiced cool the next. When Cooper begins to understand how difficult it will be for him to leave with his daughter in tow, Hartnett injects a touch of nerves into Cooper’s every move. His smiles grow more forced, his lies more complicated, his stance more stiff—enough for Riley to notice that something’s off.

Hartnett’s performance unlocks the film’s unusual charm. Trap may be nonsensical, with massive plot holes, but it’s not mindless. Shyamalan is able to both unnerve and tickle his audience whenever he keeps the film firmly in Cooper’s perspective. To a serial killer, Trap suggests, everything that everyone else considers normal is actually unnatural, maybe even hilarious: Cooper seems to take pleasure in darting between his seat and the rest of the arena, setting up distractions that delight him and disturb everyone else, all so he can make his way through throngs of concertgoers and police officers. The dialogue he exchanges with anyone he meets is stilted, with long, strange pauses, as if in Cooper’s mind, ordinary people are too slow to keep up with him. The effect is a film that’s oddly funny, right down to a mid-credits scene played for laughs. Cooper’s preposterous jaunts into restricted areas and back to Riley play like a heightened version of the Mrs. Doubtfire restaurant scene, and the plot giddily contorts itself in directions I won’t spoil. I’ll just say that each time the story progressed after reaching what seemed like a narrative impasse, I could practically hear Shyamalan rubbing his hands together, cackling at what he’d done.

Like his other recent movies, Trap extracts mundane fears about parenting from its ludicrous story. Cooper’s psychopathy is rooted in a strained relationship with his mother, but he’s managed to be a good dad to Riley. At the concert, he’s angry that his identity as the Butcher has gotten in the way of his daughter having a good time—something she desperately needed after being ostracized from her friend group. Trap posits that although parents understand things about their children more than anybody else, they can’t control what happens to them, always keep them safe, or avoid inadvertently hurting them. This poignant message, despite Shyamalan’s best efforts, comes off a tad underbaked as the film goes on. The suspense around whether Cooper will get caught overwhelms whatever suspense there is around Riley’s relationship with her dad falling apart.

Shyamalan told my colleague David Sims that he considered the chaos of Lady in the Water, one of his biggest box-office failures and most critically derided films, to be a kind of “jazz.” That description could apply to Trap as well—it’s a disorderly project, full of off-key, seemingly atonal beats that will likely alienate viewers hoping for more conventional horror-movie scares. Yet it also builds to a cohesive whole, and the movie’s peculiarity is gratifying at this stage in the director’s career. At its core, Trap is so very Shyamalan. Look at it this way: A film about a serial killer turned out to be endearingly ridiculous. How’s that for a twist?