The Secret Desire Many Workers Share

6 min read

Join The Atlantic’sstaff writer James Parker and its editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, for a discussion about Parker’s new book, Get Me Through the Next Five Minutes: Odes to Being Alive. The conversation will take place at Politics and Prose at The Wharf, in Washington, D.C., 610 Water Street SW, on August 12 at 7 p.m.

How good must it feel to march up to a truly terrible boss and unload every frustration you have with your job? I’ve never done it, and I don’t actually want to—I have a pretty nice gig right now. But the intense, vindictive impulse to tell off an incompetent manager, or lose your cool with an infuriating co-worker, or simply say no to someone who’s telling you what to do is, I think, a secretly cherished fantasy of basically anyone who works for a living. This week, Chelsea Leu assembled a list of books to read when you’re ready to toss your uniform to the ground and walk out of your shift.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s books section:

- This is not your typical campus novel.

- “Composition With Birds,” a poem by Zbigniew Herbert, translated by Alissa Valles

- When realism is more powerful than science fiction

- A marriage that changed literary history

Her picks include, of course, “the most famous quitter in literature,” Herman Melville’s “pale, mild-mannered Bartleby,” who tells his befuddled boss “I would prefer not to” when asked to complete a task. And her list made me think of a contemporary example: Kristi Coulter’s Exit Interview, a sharp and insightful memoir I’ve recommended to my social circle of ambitious late-20s career women. It details Coulter’s ascent at Amazon, and what ultimately led her to walk away, with humor and style. (The book is worth reading for her voice alone.)

Exit Interview is also a fascinating document of more than a decade of being female in the male-dominated tech industry. With appropriate rage and frustration, Coulter lays out her ledger of all the slights that piled up over the course of her career: male colleagues’ crude jokes, years of being passed over for promotions, an intense company culture that pushed her into alcohol addiction. But she also captures what made Amazon so alluring, particularly the pure rush of solving problems that no one else could crack. And the money, of course—she made lots of money, though in her retelling she struggles to explain to her husband that she doesn’t “feel overpaid. Amazon could be depositing a million dollars a month into my checking account and I would think, Yes, this seems about right, given the fear and the chaos and the ugly surroundings and the endlessly escalating demands and the way no one ever says thanks.” When she’s recalling that moment of self-deception, she includes the voice of clarity that, at the time, she ignored: Her husband reminds her that it’s her choice to keep this maddening, health-ruining job. “Just stop bullshitting yourself that you can’t,” he tells her. “You can leave anytime. You’re choosing to stay.”

Readers who want an honest accounting of the ethical costs of Coulter’s job won’t find it: Her role, she writes, was totally insulated from Amazon’s behemoth goods-delivery infrastructure, where “workers spend their days picking and packing in million-square-foot warehouses where they face punishing productivity expectations, constant surveillance, high turnover, and serious injuries,” as my colleague Ellen Cushing reported in 2021. Two years earlier, The Atlantic had published Will Evans’s report on how “the company’s obsession with speed has turned its warehouses into injury mills.” Coulter does not defend Amazon, and she’s not interested in trying to untangle her complicity—because that’s not what her story is about. At the beginning of the book, she writes, “I’m not telling you what was right or good. I’m telling you what went down and how it felt.”

When I finished the memoir, I told all my friends—women with a litany of unremarkable stories about bad bosses, standard harassment, and unrewarded perfectionism—to read it, and to think about what we really gain from working ourselves to the bone. It’s certainly a book that stokes any embers of the desire to walk into a superior’s office and just quit.

What to Read When You Want to Quit

By Chelsea Leu

These titles help readers think through pressing questions about modern employment—including whether it’s time to walk away.

Read the full article.

What to Read

The Games Must Go On: Avery Brundage and the Olympic Movement, by Allen Guttmann

The modern Olympics are hard to understand without first understanding Avery Brundage, an American athlete, a Chicago real-estate developer, and, later, president of the International Olympic Committee. His style was brash: He wasn’t afraid to ban a top competitor, or to wave away the need for women’s sports. But, as Guttmann argues in his definitive biography of this morally complicated man, perhaps no one shaped the governance of the Olympics more. Brundage helped turn the Olympics—once a clubby, largely European affair—into a truly global institution. He was an early advocate of expansion, pushing for a Japan-hosted Olympics in 1940 (though those Games were canceled because of the war). He helped persuade the U.S.S.R. to participate for the first time, instituted the first anti-doping controls, and cemented the sex-testing policies that would shape who was allowed to compete in women’s sports for decades to come. Brundage also solidified the IOC’s generally agnostic relationship with world politics. He saw no issue with allowing the Nazis to host the Olympics in 1936, writing that the Olympics must not get involved in politics. Years later, as leader of the IOC, Brundage stuck to those beliefs: In the 1960s, after the United Nations tried to ban apartheid South Africa from competing, Brundage pushed to allow the country to participate anyway. Guttmann untangles Brundage’s many failures all while acknowledging that, for better or worse, he is the reason the Olympic Games exist as they do today. — Michael Waters

From our list: Seven books that will change how you watch the Olympics

Out Next Week

📚 Kent State, by Brian VanDeMark

📚 Men Have Called Her Crazy, by Anna Marie Tendler

📚 Peggy, by Rebecca Godfrey with Leslie Jamison

Your Weekend Read

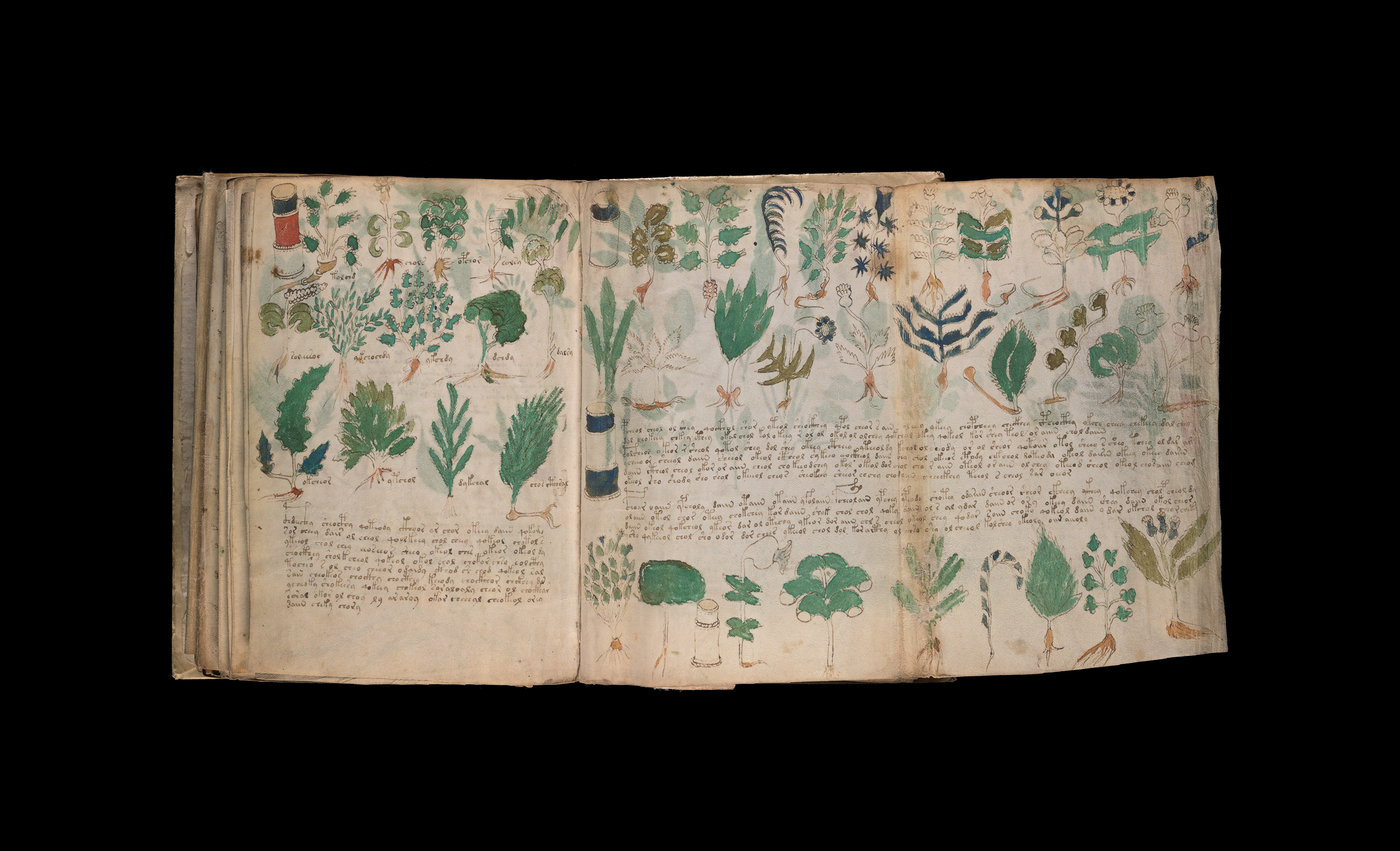

An Intoxicating 500-Year-Old Mystery

By Ariel Sabar

The Voynich Manuscript had reentered [Lisa Fagin] Davis’s life, forcing her to reconsider almost everything she thought she knew about it. The manuscript’s notoriety—as history’s hardest puzzle; as grist for unhinged conspiracies—had for many years scared scholars away. But what if you looked past its extravagant strangeness? What if you focused instead on the things—little noticed—that it shared with countless other manuscripts?

Could the ordinary illuminate the extraordinary? Davis resolved to find out.

Read the full article.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Explore all of our newsletters.