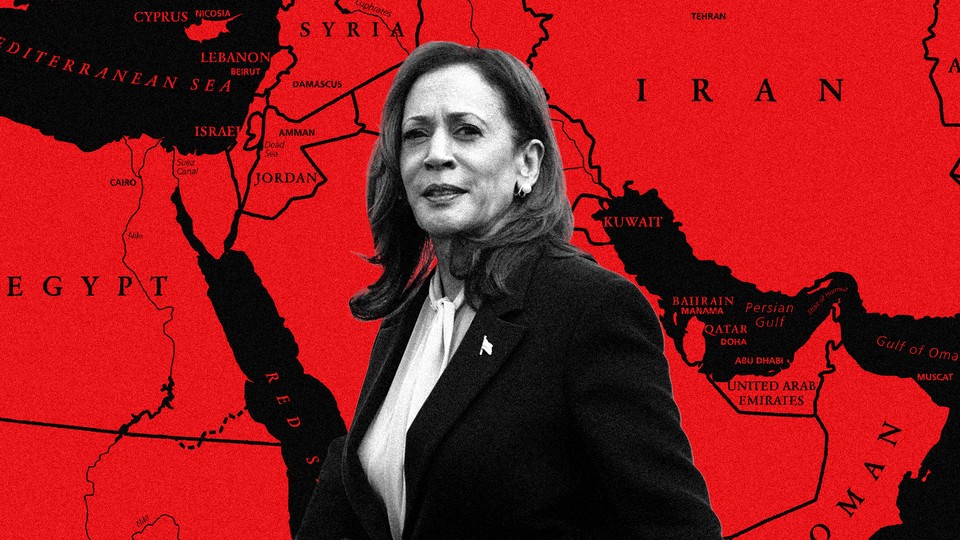

Does Kamala Harris Have a Vision for the Middle East?

6 min read

The administrations of Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden have all shared one common foreign-policy desire: to get out of the quagmire of the Middle East and focus American attention on the potentially epoch-making rivalry with China. Even in fiendishly polarized Washington, foreign-policy hands in both the Republican and Democratic Parties largely agree that the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq was an unmitigated disaster, and that the United States should reduce its involvement in the region’s squabbles.

But like the Hotel California, the Middle East doesn’t let you leave, even after you check out. Obama and Trump both made historic deals purportedly to increase stability in the region and allow the United States to pivot elsewhere. But unexpected events popped up for both as well as for Biden, pulling them back in and leading them to expend much of their energy there.

Kamala Harris can expect no different if she wins the presidency in November. But the approach she’s likely to take to the region isn’t obvious. In general, Harris is difficult to pin down—a politically versatile operator, which has worked to her benefit so far, allowing all wings of the Democratic Party to see in her what they like. Critics of Biden’s staunch support for Israel hope she’ll be more amenable to pressure from the left on this issue, while centrists find her reliably pro-Israel track record in the Senate reassuring.

Harris doesn’t come without experience in the Middle East, but a recap of her encounters isn’t especially illuminating. Her first-ever foreign trip as a senator was to Jordan in April 2017: She visited Zaatari, the world’s largest camp for Syrian refugees, and called on then-President Trump to “articulate a detailed strategy” on Syria’s civil war, in which President Bashar al-Assad had just carried out a gruesome chemical attack on civilians. Shortly afterward, she went to Israel and met with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Her legislative record on the Middle East offers only a few bread crumbs. In 2017, a United Nations Security Council resolution condemned Israel’s settlement-building in the West Bank. The Obama administration chose not to veto that resolution. Harris co-sponsored legislation objecting to that decision, on the grounds that the UN resolution was one-sided and would not advance progress toward a two-state solution, better achieved through bilateral talks. A year later, she deplored Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, which she said was “the best existing tool we have to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons and avoid a disastrous military conflict in the Middle East.” She later recommended reviving that agreement and extending it to cover Iran’s ballistic missiles. She voted to cut off U.S. aid for Saudi Arabia in its war in Yemen, even while acknowledging Riyadh as an important partner for Washington.

All of these points, taken together, are more suggestive than definitive. And so those who seek to understand Harris’s future foreign policy tend to look to the much more elaborated worldview of Philip Gordon, the vice president’s closest adviser on Middle East affairs and her national security adviser since 2022. Now 62, Gordon served under President Bill Clinton as well as Obama and has written dozens of articles and books. The late Martin Indyk, a former U.S. ambassador to Israel, noted last year that Harris “depends heavily on Phil’s advice given his deep experience and knowledge of all the players.”

Immediately after Harris emerged as the likely Democratic nominee, some supporters on the left eagerly seized on Gordon’s book Losing the Long Game: The False Promise of Regime Change in the Middle East as a likely indicator of his, and therefore her, opposition to deposing unfriendly regimes by force. At the same time, Iran hawks began attacking Gordon as a past advocate of the Iran deal, which he helped bring about as Obama’s Middle East coordinator from 2013 to 2015. Republicans in Congress have already written to Harris inquiring about Gordon’s ties to Rob Malley, Biden’s former Iran envoy who was put on leave last year because of an investigation into his handling of classified information (Gordon, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and Malley were soccer buddies in the late 1990s).

But Gordon is no secret Beltway radical. He is a policy wonk who draws respect from many quarters. A Europeanist who fell in love with France at an early age, he got his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins, where he wrote his dissertation on Gaullism; he once translated into English a book by former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, probably that country’s most Atlanticist leader in modern history. Gordon’s early interests have reassured some in Europe who initially feared that Harris’s West Coast origins would incline her more toward Asia.

Gordon has served only in Democratic administrations and spent the George W. Bush and Trump years outside government, often sharply critiquing Republican foreign policy. When Israel fought Lebanon’s Hezbollah in 2006, Gordon co-wrote a Financial Times op-ed that called Washington’s support for the war “a disaster.” A year later, he published Winning the Right War, a book-length critique of Bush’s Middle East policy that advocated withdrawing from Iraq and Afghanistan, engaging Iran with a mix of sanctions and talks, and bringing about an Arab-Israeli peace. The book anticipated the main foreign-policy goals that both Obama and Trump would pursue in the region—but Gordon’s suggested Arab-Israeli peace included a Palestinian element that Trump’s Abraham Accords did not.

Of course, a President Harris would have not one foreign-policy adviser but a full array of them, spanning the military, diplomatic, and intelligence communities. And one more name has emerged in the past week: Ilan Goldenberg, an Israeli American Middle East hand who has advised Harris on the region throughout her vice presidency. Harris has appointed him her liaison to the Jewish community and tasked him with advising her campaign on Israel, the war in Gaza, and the broader Middle East.

Goldenberg’s profile is similar to Gordon’s, in that he is not an ideologue so much as a policy professional who served the Obama administration in top Middle East–related positions in the Pentagon and State Department. He has long advocated for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He supported the Obama administration’s Iran policy, but after the nuclear deal was signed, Goldenberg also called for smoothing relations with Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf states that had been unnerved by the administration’s focus on Iran. This concern wasn’t shared by many Democrats at the time.

Harris’s lack of a grand vision for the Middle East might prove to be a blessing. After all, America’s last “visionary” foreign-policy president was George W. Bush, whose big ideas about the Middle East produced the Iraq War. When Bush’s father first considered running for president, in 1988, he famously gestured at the need for “the vision thing.” But George H. W. Bush, in contrast to his son, would go down in history as a thoughtful decision maker who listened carefully to sharply conflicting advice from his Cabinet. Less than a year into his term, he confronted some of the most dramatic events in recent history, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and then the Soviet Union. He remains a widely praised foreign-policy president among both Democrats and Republicans because of the results he helped secure—including a united and democratic Europe and a sovereign Kuwait.

So far, little is known about who else Harris would draw into shaping her foreign policy, or even whether Harris is likely to assemble a diverse team or one that resides comfortably in a single political camp. Still, Gordon’s and Goldenberg’s long and serious engagement with Middle East affairs suggest that Harris will resist the temptation to simply wash America’s hands of a seemingly troublesome region. Perhaps they are the start of a foreign-policy team that recognizes dealing with the Middle East as unavoidable, and that integrates it with policies focusing on other regions, rather than viewing it as a rival to them.