Prosthetic Limbs Have Become Billboards

6 min read

The first time Angel Giuffria saw the logo on her bionic hand, she felt a sense of pride. She was born without the lower half of her left arm, and started wearing a prosthesis at six weeks old. Back then, it had a beige cover—a design that was meant to mimic skin, but looked obviously fake. This new hand abandoned any unsettling attempt at imitation. Instead, it had a Star Wars–like aesthetic. Giuffria was delighted. She felt like it allowed her to celebrate, not conceal, being a prosthetic-wearer.

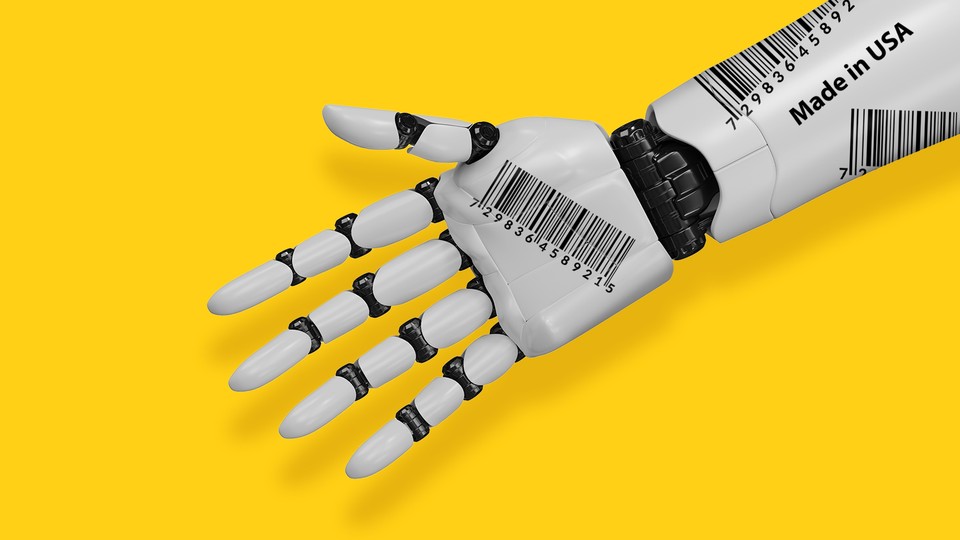

But the more she stared at the brand’s orange-and-black logo slapped across the top of the hand, the more she felt that she’d become a walking billboard, she told me. Bionic (or myoelectric) limbs, which are operated by muscle and nerve impulses to more closely mimic the movements and operation of a real limb, have evolved dramatically in the past few decades. And because they offer so much more movement control, these droid-like devices and their accessories have become more prevalent among prosthetics users. They also nearly universally feature branding. Logos on distal parts (hands, feet, ankles, wrists) are the most visible, but companies brand other parts of a limb, too: tightening knobs, silicone liners, socks, and running blades. Fully adopting a prosthesis as an extension of one’s body can be challenging to begin with, but many prosthetics users have found that branding only makes this harder.

I’ve had this experience myself. Like many other amputees, after seeing a cosmetic prosthesis that reminded me most of a severed hand, I opted for a more mechanical mien. But plastered across the top of the bionic hand I wanted, in traffic-cone orange and black, was the device’s name, BeBionic. Wearing parts that nearly all have logos on them feels like someone else now owns bits and pieces of me. The silicone liner that my prosthesis attaches to has a QR code near the top and WillowWood printed along its length. My elbow joint reads Ottobock, and the adjuster used to tighten my socket has BOA running across it in silver letters. Imagine someone approaching you with a tattoo gun and asking to put a QR code on your body. Such marks on a prosthesis send the message that the limb isn’t fully yours.

Not everyone minds the branding. Dayna Troisi, who previously wore the BeBionic, told me that she liked having the word bionic on the hand, because it kept people from asking questions like “What is that?” and “How does it work?” (She did hate that the logo was orange.) And branding can certainly be desirable—90 percent of my T-shirts have Taylor Swift graphics on them. Many people take pride in broadcasting their opinions and preferences through their sartorial choices. A logo can represent self-expression and even belonging.

A prosthetic limb, though, is different, because it’s both part of someone and a product of necessity. Many prosthetics users find that the branding gets in the way of feeling ownership of our prosthetic limbs. A prosthesis will never replace a person’s flesh, but liking its appearance can have a huge impact on one’s ability to assimilate with it. Jo Beckwith, a public speaker and content creator who raises awareness about limb loss, dislikes the portion of her liner that’s covered in an ugly company logo. “But that’s my leg,” she told me.

Giuffria is an actor, and she told me that after she booked a film wearing the BeBionic, the crew questioned whether displaying the hand would require clearance from the company. “It felt awful,” she said. Because she didn’t have permission to display the logo, the prop department used a vinyl sticker to obscure it. After that, “I really hated the logo,” she said. “It made my arm seem like a product, rather than my body. The logo made it seem less a part of me, which invited others to treat it that way.”

Many of the companies that make prosthetic parts remain committed to branding, though. It is, after all, a primary way to distinguish their product and attract customers—not just prosthetics users, but the clinics, prosthetists, and technicians who recommend them and the insurance companies that in many cases pay for them.

Össur, for example, offers some of the most innovative prosthetics on the market, and places its logo on nearly everything. The executive vice president of research and development for Össur’s parent company, Hildur Einarsdóttir, told me that Össur had scaled back the branding on the popular iLimb hand after acquiring the company that originally made it. But it still has a label across the top of the wrist that reads Össur i-Limb Quantum. Össur extends the branding to lower-extremity parts such as feet and knee joints, even adding visible serial numbers, which Einarsdóttir said is to ensure that these mass-produced parts are traceable. (But serial numbers can also be stored on a chip within the parts, as Esper Bionics does with its Esper Hand.)

For Ottobock, which makes the BeBionic hand, the logo represents the company’s “commitment to quality,” says Scott Schneider, the head of government, medical affairs, and future development at Ottobock North America. And although the company welcomes feedback from those who would rather avoid branding, he told me, Ottobock will keep its logos visible. The company has made the logo on the BeBionic smaller and done away with the orange, but it added the word Ottobock right on the back of the hand.

Once companies have branded their products, tidily and permanently painting over or erasing the logos can be challenging and expensive. Generally, a clinician will offer to customize a limb’s socket (the part that covers the residual limb). But many prosthetics techs are hesitant to alter bionic parts. Damage the product while customizing it, Dez Joseph, a prosthetist and orthotist in New York City, told me, and that could invalidate the warranty on a device that can cost as much as or more than a Jaguar.

Insurance also won’t cover the work, because it’s considered cosmetic, Joseph said. And because getting insurance approval for prosthetics can already be a battle, for some people professional customization is effectively impossible. Certain companies, such as Ottobock, offer gloves made to resemble hands (complete with wrinkles), which conceal any labeling, but Schneider and Joseph both told me that these covers can hinder some of the device’s efficacy.

Instead of aggressive branding, some companies have focused on creating a distinct visual identity for their products—making certain prosthetics as instantly recognizable as an iPhone to those in the know. The Esper Bionics hand, voted among the best inventions of 2022 by Time magazine, is slick and devoid of markings—I think of it as the dolphin of hands. It’s clearly not trying to pass as flesh, but it doesn’t call attention to itself.

Really, choice is key. A newer prosthetics company called Taska has its branding on an interchangeable faceplate that a prosthetics technician (or a crafty friend) could paint without damaging the hand. If the point of a prosthesis is to enhance bodily autonomy, that has to include control of what our bodies look like. My next arm will be inspired by Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poet’s Department: I want it wrapped in holographic white vinyl with a friendship-bracelet arrangement, featuring all of my favorite lyrics, hand-painted on the wrist. But if my prosthesis came pre-stamped with a Taylor Swift theme, that would be an imposition. As my favorite song on the album says, “I’ll tell you something about my good name, it’s mine alone to disgrace.” My body, too, is mine alone to mark.