Inside the Virginia Newsroom Trying to Save Afghanistan From Tyranny

11 min read

In late 2022, a reporter in Afghanistan received a tip that members of the Taliban had raped a mother and her four young daughters in the Panjshir Valley, just northeast of Kabul. The journalist goes by an assumed name—Sahar Aram—for fear of retribution from the Taliban, which has ruthlessly cracked down on Afghanistan’s free press. So she relayed the information some 7,000 miles beyond the group’s reach, to a quiet Virginia suburb where a pair of exiled Afghan journalists had recently launched a newsroom.

Even though it operates abroad—or perhaps because it operates abroad—Amu TV is one of the most effective chroniclers of life under Taliban rule. With one of Amu’s editors, Aram devised a plan to travel to Deh Khawak, the remote village where the tip originated. The Taliban had barred outsiders from entering the town, so Aram disguised herself from head to toe in colored fabric native to the area. Because the group had cordoned off the victims’ home, she maneuvered from neighbor to neighbor, probing for evidence. When a Taliban official sent her a voice message confirming the incident, Aram reported her findings through an encrypted portal. Soon after, Amu published the story online. Afghans around the world read Aram’s work, which apparently enraged the Taliban: They set out to find her.

She went on the run but continued reporting. Several months later, she investigated a Taliban official accused of sexual harassment. Then a group of men—which she believes was linked to the Taliban—beat her father unconscious. A judge accused Aram of defamation and ordered her arrest.

“I am not afraid to die for this work,” she told me over the phone from her hiding place. “But if the Taliban are going to make an example out of me, I need to be sure the stories count.”

Aram’s experience is hardly unusual. Before the Taliban took over the country in August 2021, Afghanistan’s news media had been one of the great successes of the country’s American-led, post-9/11 era. Journalism and entertainment flourished in the two-decade window that followed the Taliban’s ouster in 2001.But when the last American soldiers retreated, the industry collapsed. The Taliban threatened, beat, or imprisoned dozens of journalists. TV stations, radio channels, and publications across the country shut down under immense financial and political pressure.Hundreds of journalists fled, dozens were detained, and at least two were killed.The Taliban scrubbed music from television and radio programming, and largely banished female news anchors. TV networks replaced government exposés with shows about Islamic morality.

Three years later, the Taliban is escalating its war on journalism. The group recently imprisoned seven Amu staffers. Some have been beaten and tortured. More have been forced into hiding, as Aram has.

The story of Amu TV and its journalists offers a warning: Afghanistan’s new rulers aren’t content with the power they have. True autocracy requires impunity, which Amu and its peers can deny the Taliban—at least in part, at least for now. But arrests, abductions, and raids are making that task harder. Judging by Amu’s experience, the Taliban could soon make it impossible.

Amu’s operation depends on the scrappy ingenuity of its far-flung staff. After Kabul fell, the network’s journalists dispersed across the Middle East, Europe, North America, and elsewhere. A team in Tajikistan records musical segments. Producers dub over Turkish soap operas that have been banned in Afghanistan. Staffers in Pakistan and Iran balance their day jobs with evading local authorities. Some have applied for asylum or permanent housing and received neither.

Like other Afghan outlets whose editorial staff operate outside the country—such as Hasht e Subh, Afghanistan International, and Etilaat Roz—Amu editors assign news-gathering to reporters inside Afghanistan and then piece stories together from stations abroad. Some 100 reporters in the country, mostly women in their 20s and 30s, risk their lives to expose the Taliban’s crimes and corruption. Together with more than 50 exiled Afghan journalists, including about a dozen in Amu’s Virginia headquarters, they generate daily online news coverage and television programming.

The Taliban blocks Amu’s website in Afghanistan, as it does many other foreign outlets. But according to data its editors have gathered, about 20 million people access Amu’s digital platform each month; many use a virtual network to skirt the firewall. A license with a Luxembourg-based satellite company, SES, enables Amu to transmit its TV programs into Afghanistan, where the provider serves about 19 million people.

Perhaps the best measure of Amu’s significance, though, is the effort the Taliban has expended to intimidate it. Amu’s investigative reporting on cases of rape, corruption, and extrajudicial killings has provoked the group’s wrath.On the morning of March 12, 2023, the Taliban raided an office space Amu was using in Kabul. The intruders detained staffers, including a video editor and a video journalist, and seized mobile phones and computers, which Amu’s editors believe were used to identify people on its payroll. Last August, the Taliban abducted five more Amu journalists.

The Taliban incarcerated, beat, and tortured Amu staffers, in some cases for months. Amu’s leadership appealed to the United Nations, the U.S. embassy, and advocacy groups for help. After weeks of lobbying, Amu’s journalists were released. The newsroom has since erased all records of its official payroll and distributes funds via couriers or wire transfers to relatives of staff living abroad.

Since August 2021, at least 80 journalists in Afghanistan have been detained in retaliation for their work, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. “The situation is dire,” Beh Lih Yi, the Asia program coordinator for the CPJ, told me. “It shows how determined [the Taliban is] to crack down on the free flow of information by targeting foreign news outlets, like Amu, that have become critical lifelines for keeping the world informed.” Over the past year, the CPJ says, the Taliban has arrested at least four journalists on claims that they were working for exiled media. Every day, Lih Yi told me, the committee receives calls from Afghan reporters needing help.

When I visited Amu’s headquarters in Virginia last November, one of its co-founders, Sami Mahdi, was running late: His uncle had an interview with immigration officials that morning and needed someone to help translate. “Some days we are refugees first, then journalists,” Mahdi said as he hurried into an office where dozens of colleagues from around the world waited on-screen.

Mahdi founded Amu in the fall of 2021 with a former colleague, Lotfullah Najafizada. Back in Afghanistan, the two had worked together at Tolo News, the country’s premier news network. Growing violence in the region made their lives untenable. In November 2020, three Islamic State gunmen stormed Kabul University, where Mahdi was teaching, and killed 16 of his students. Days later, Afghanistan’s intelligence agency notified him that he was a target of the Taliban’s Haqqani network. That same month, insurgents assassinated a close friend and fellow journalist. Fearing he was next, Mahdi fled Afghanistan for good on August 14, 2021, when nearly all the American soldiers had retreated. Najafizada left the same day.

Hours after Kabul fell, Najafizada got a call from a member of the Taliban, who told him the group was sending a delegation to Tolo’s offices to go on air and publicly assure the country that everything was under control. “At that moment I knew it would be impossible to work with media in the country,” Najafizada told me.

Mahdi and Najafizada reunited in Turkey, where they decided that if they couldn’t freely publish the news inside Afghanistan, they would do so abroad and beam it back in. “We needed to start something from scratch,” Mahdi said. “We wanted a way to access information we could trust. And we wanted something for everyone: something that would unite our exiled colleagues, preserve what we had spent our lives building, and restore a sense of normalcy for Afghans.”

Soon after they settled in North America, Mahdi and Najafizada raised close to $2 million in seed money and recruited former co-workers and friends. A distant relative of Mahdi’s contributed the office space in Virginia that now serves as Amu’s newsroom. The National Endowment for Democracy and other donors keep the lights on.

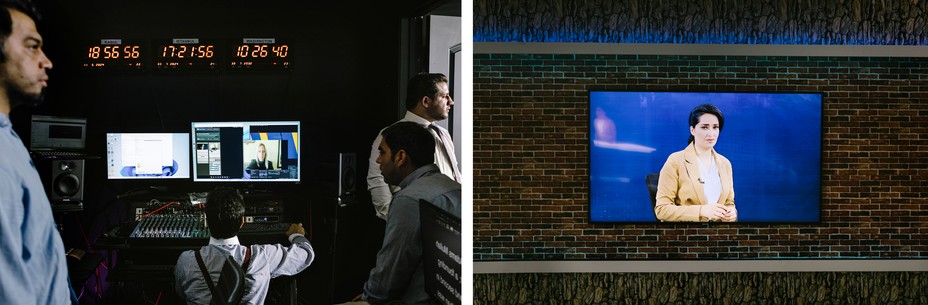

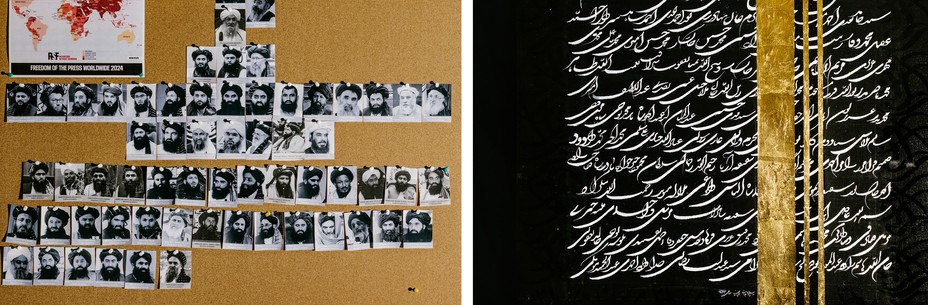

The headquarters sit above a string of nondescript offices in Sterling, about 45 minutes outside of Washington, D.C. In a control room, clocks show the time in Kabul and in Turkey, where Amu operates a second studio. A wall of muted televisions flashes headlines in Pashto and Dari. Every corner of the newsroom offers a reminder of what Amu’s reporters face back home. A large painting outside Mahdi’s office incorporates the names of dozens of Afghan journalists killed over the past two decades. On the opposite wall, a corkboard displays headshots of the Taliban leadership.

For Amu’s star anchor, Nazia Hashimyar, the women’s bathroom doubles as a makeup studio. The 28-year-old doesn’t wear a head covering on-screen, even when she interviews Taliban leaders. Like many of her colleagues, Hashimyar left Kabul shortly after the takeover. She remembers the traffic that choked the city on the day it fell—the overrun tarmacs, the futile phone calls to people who might have answers about evacuation lists or news of a missing loved one.

Early that August morning, Hashimyar stood on the lawn of the presidential palace as Afghanistan’s leader, Ashraf Ghani, boarded a helicopter and fled the country. She had been working in Ghani’s communications office while moonlighting in what she called her “dream role”—hosting the evening news for Radio Television Afghanistan, the country’s public broadcaster. The Taliban removed her from her anchor job on the day it took the capital. After spending several weeks in hiding, Hashimyar returned to her office to retrieve her belongings, only to be turned away by a gunman who threatened to shoot her.

Hashimyar spent a year in a refugee camp in Abu Dhabi before she was approved to settle in the United States in September 2022. She arrived as Mahdi was looking for a female anchor to be the public face of Amu’s news coverage. The sense of safety and accomplishment that she’s found in the U.S. comes with the deep discomfort of having escaped what so many others couldn’t. “Physically I am somewhere in the suburbs of America,” she told me. “But my heart and mind cannot escape Afghanistan.”

Mahdi has done his best to make the newsroom a home for Hashimyar and the rest of the staff. “We needed a space to gather, to help us bridge the two worlds we are straddling between the United States and Afghanistan,” he told me. He hosts parties in the office for other Afghan journalists and writers in the region. An Afghan chef a few doors down handles the catering. Every morning the newsroom gets free meals and fresh naan.

Mahdi has known for a long time what exile is like. He was 13 when the Taliban first came to power in Afghanistan. His family fled to Tajikistan, where his father oversaw a newsletter compiled by exiled writers, activists, and editors, who received dispatches via satellite phones from correspondents back home. Mahdi wouldn’t return for another five years.

“Becoming a refugee again was always my greatest fear,” he told me.

Amonth after visiting Amu’s headquarters in Virginia, I went to see one of its editors who had settled in the suburbs of Paris. When I arrived, Siyar Sirat was working with reporters to investigate the death of a female media personality in Kabul. The Taliban had said in a statement that she had been drunk when she fell from her apartment. On a call, Amu’s editors discussed an interview with the woman’s parents and husband that had been uploaded to YouTube that morning. The editors thought the video looked staged. It shows the woman’s family saying that she threw herself from a window after arguing with her husband. Harder to see is a man in the background, who appears to be holding a Kalashnikov.

The editors sent a female reporter to investigate further. But when she arrived on the scene, she was barred from entering the building. The neighbors she tried to talk to turned her away, insisting it was too dangerous to speak. The reporter, who goes by the name Sima, asked to be taken off the story because people were scared to cooperate.

“From where we sit, it looks like a clear cover-up,” Sirat told me. “But our hands are tied: It is becoming impossible to cover such sensitive cases given the circumstances.” Several weeks later, the Taliban’s Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice arrested dozens of women and girls for not wearing proper head coverings. Sima tried to cover the story, but once again she struggled to find sources or relatives who would speak.

Amu’s Hasiba Atakpal, a 26-year-old broadcaster based in Virginia, has encountered the same problem. She worries that Afghans will soon stop talking with reporters entirely because of the Taliban’s mounting persecution of foreign media and women across the country. Before she settled in Virginia, Atakpal was a household name in Afghanistan as a correspondent for Tolo News. In August 2021, she and her film crew broadcast live in Kabul during the takeover, prompting a Taliban leader to threaten her. Atakpal left the country for her safety.

Now that she covers the Taliban from afar, she has had to transform her reporting method.Rather than investigate stories with videographers on the ground, Atakpal patches together broadcasts from WhatsApp voice notes, recorded calls, and videos from inside the country, which she combines with voice-overs. The Taliban and others continue to harass her in exile. Fake social-media accounts have impersonated Atakpal in a clear effort to undermine her credibility.Last year, after she producedan antagonistic interview with Kabul’s police spokesman, she received a message from a Taliban official demanding her family’s location. On multiple occasions, her colleagues in Afghanistan have gone missing, including a young female videographer who was recently abducted by the Taliban.

“The responsibility is crippling,” Atakpal told me. “The reporters who remain, who cannot be seen, are the true heroes. More than anything, I wish I could be in their place.”