The Limits of Diplomacy With China

5 min read

As China’s leader, Xi Jinping, intensifies his campaign to reshape the U.S.-led global order, the big question hanging over international affairs is: How will he choose to do it? Xi purports to be a man of peace, offering the world fresh ideas on diplomacy and security that could resolve global conflicts. Yet his actions—above all, his moves to deepen a partnership with Russian President Vladimir Putin—suggest that he presents a new threat to global stability, and instead of bringing security, he is facilitating forces that create turmoil.

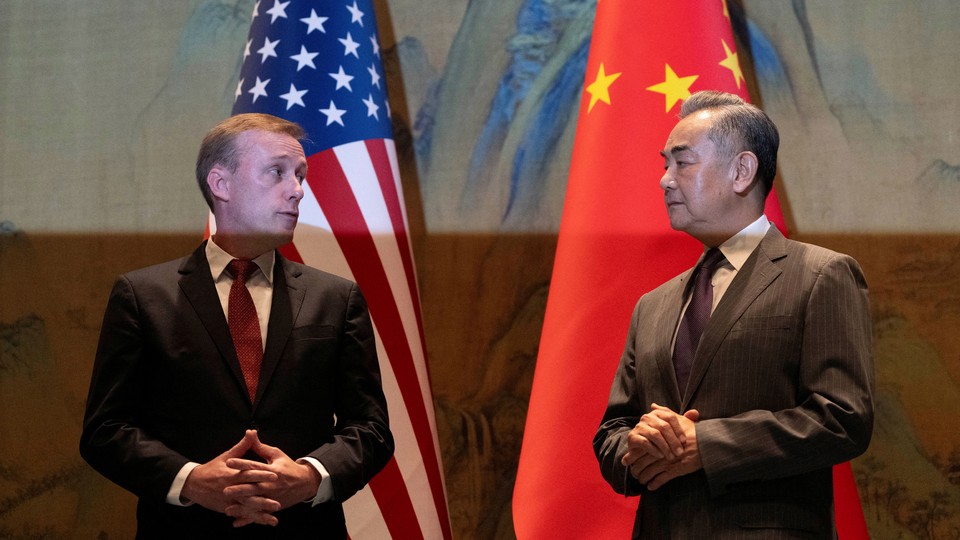

This was a key issue that U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan faced during his visit to Beijing this week. On the table was China’s support for Putin’s devastating war in Ukraine and American efforts to stop it. Part of Sullivan’s mission was to persuade China’s leaders to cooperate more with the United States.

“I’ve sought to impress upon my Chinese interlocutors that they need to recognize the American history with European security,” Sullivan told me. “There is no more profound issue for us in our foreign policy.”

Whether Sullivan made any progress remains to be seen. For now, China’s leadership may be inclined to wait for the outcome of November’s U.S. presidential election to see if it can get a better deal from someone other than President Joe Biden. Beijing may judge that its prospects of achieving that are distinctly better if the winner is Donald Trump, whose pronouncements are more sympathetic to Putin than to NATO.

China’s challenge to U.S. global leadership won’t go away, regardless of who wins the White House. Unmoved by the rising death toll in Ukraine, Xi has strengthened China’s diplomatic, trade, and business ties with Russia. Similarly, in the Middle East, Xi has maintained close links with Iran, despite the violence caused by the Yemen-based Houthis and other Tehran-backed groups.

“We’ve seen Xi Jinping indulging in the temptation to promote chaos,” Matthew Pottinger, a former deputy national security adviser and now the chair of the China program at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, told me. “He is trying to advance power and influence through riskier means, mainly proxy warfare in Europe and the Middle East. We’ve got our work cut out to make him think thrice before pushing that line of strategy harder.”

Whether Beijing fully intends to promote instability through these relationships is a matter of debate. China has so far scrupulously avoided providing direct military aid to Russia, in contrast to Washington’s supply of arms to Ukraine. Xi has many reasons to develop a close relationship with its Russian neighbor—such as securing energy resources and a market for China’s industrial exports—that have little to do with the war. Despite Xi’s lofty language about peace and justice, his foreign policy typically revolves around more pragmatic political and economic interests.

Yet Xi has also shown little willingness to rein in his partners. Hopes in Western capitals that Xi would use his influence with Putin to help end the Ukraine war were dashed long ago. Beijing reportedly leaned on Iran to intercede with its Houthis allies and end their attacks on shipping in the Red Sea. That failed to happen, which suggests either that Xi’s effort was half-hearted or that Beijing has limited sway in Tehran.

In addition, China’s leaders must be aware that their continued commerce with Russia and Iran, which both face Western sanctions, buoys the two countries’ economies and consequently their ability to sponsor conflict. In Russia’s case, Beijing’s complicity in Putin’s Ukraine war is more brazen, and Western leaders have accused China of enabling Moscow’s war effort with crucial supplies.

Sullivan explained to his Chinese counterparts “how vital an interest European security and the trans-Atlantic relationship is to the United States,” he told me. “The contributions of Chinese firms to the Russian war machine don’t just impact the war in Ukraine, though that’s of enormous concern to us; they also enhance Russia’s conventional military threat to Europe.”

Washington has already tried to stop that support. Earlier this month, the Biden administration imposed sanctions on more than 400 companies and individuals it believes to be aiding Russia’s war effort, including Chinese firms. What Beijing would need to do is intervene with China’s own companies to curb the flow of vital components to Russia. This, after all, is something Chinese officials can clearly do—they have few scruples about cracking down on companies when it suits them.

Instead, at least in public statements, they have lashed out at Washington’s measures. According to an official Chinese-government readout, Foreign Minister Wang Yi firmly advised Sullivan that “the United States should not shirk its responsibilities to China, let alone abuse illegal unilateral sanctions.”

Sullivan put a somewhat more positive spin on the tensions. “I think there is will on both sides to put a floor under the relationship, so we don’t end up in downward spirals,” he told me. The degree of diplomatic engagement was reflected in the fact that Sullivan not only held extensive talks with Wang, but also met Xi himself, and landed a rare meeting with General Zhang Youxia, the vice chair of the powerful Central Military Commission. But the visit was not likely to produce any breakthrough. “I don’t think there’s been an underlying shift in the dynamic of the relationship,” Sullivan told me.

“I think [China’s leaders] would like stabilization while also pursuing their larger national ambition,” he said. “And we would like to pursue stabilization while also pursuing our national interests and continuing to take competitive actions, which we will.”

That means Xi will likely continue to prioritize his relationships with Russia, Iran, and other countries that he believes can aid his quest for a new world order more shaped by Chinese interests. Yet his willingness to tolerate the chaos these partners foment will be a test of his vision for that reformed order and his ability to lead it. In the end, Xi has to decide what kind of power he wants China to be: the force for stability he talks about, or the source of instability it’s becoming.