The Age of Jennifer’s Body

7 min read

Horror movies are filled with women and girls in various stages of distress: haunted blondes, bewildered wives tormented by their husband’s greed, final girls who have survived massacres that swept towns or summer camps. And who can forget Linda Blair’s bloodied head, spinning 360 degrees on her shoulders in The Exorcist, an image that has frightened sleepover attendees for half a century?

But the horror genre isn’t made up only of girls who are victims of terror. Fifty years ago, in his debut novel, Carrie, Stephen King popularized a new kind of antihero. Carrie White, the story’s protagonist, is a demonic teen girl—someone who unleashes destruction rather than survives it. This character type is often arch about her femininity and sometimes even sexually promiscuous, and she always possesses a supernatural strength that she uses to wrest the world under her control. “Things are going to change around here,” Carrie (played by a hypnotizing Sissy Spacek) tells Margaret, her fanatically religious mother, upon discovering her telekinesis, in Brian De Palma’s masterful 1976 film adaptation. Having spent much of her life being forced to pray for salvation from original sin, Carrie is set free by her unholy skill. “Witch!” Margaret hisses in response to her daughter’s talent, which Carrie only unveils so that she can obtain her ultimate wish: to go to prom.

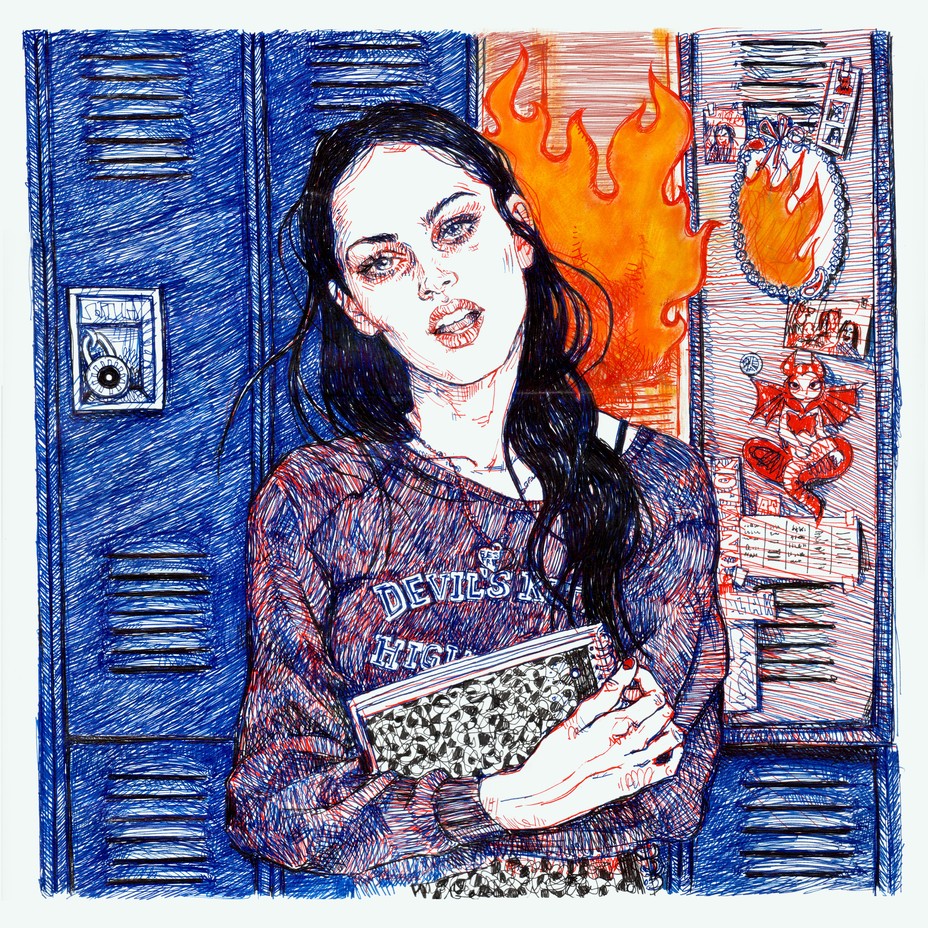

Scorned husbands, vengeful kings, and medieval courts have historically used accusations of witchcraft as a means of restraining women for a variety of reasons: their “hysteria,” their violence, their independence of mind. The demonic teen girl, whose paranormal faculties emerge alongside the new desires and burning disappointments of girlhood, is defined by these same measures––which are only intensified by the mundane cruelties of the American high-school experience. Carrie has since inspired a spate of successors; two notable examples are Nancy Downs, the power-drunk leader of her school’s coven in The Craft, and the dog-eating werewolf Ginger Fitzgerald, of the low-budget classic Ginger Snaps. But the most infamous demonic teen girl of the 21st century is Jennifer Check, the hot cheerleader turned boy-eating succubus in Karyn Kusama’s cult favorite Jennifer’s Body, written by Diablo Cody and released 15 years ago today. Although it’s fun to cheer on their bloodthirst, there’s a lot more to these girls; their ferocity is only the first layer of their intricate personalities.

Unlike Carrie, who was born with her abilities, Jennifer’s powers are the product of a satanic deal gone wrong. After surviving a fire at her town’s local dive bar, the eyelined and tattooed members of the band Low Shoulder persuade Jennifer (Megan Fox) to join them in their van, despite the protests of her best friend, Needy (Amanda Seyfried). Jennifer soon finds out that the boys want only one thing: a virgin to sacrifice to the devil, in exchange for career success. But Jennifer is not a virgin, so instead of dying, she becomes a flesh-hungry demon with a preference for her male classmates. Catching on to the fact that Jennifer looks oddly cheery and sexy even as brutal murders ravage their small suburb, Needy sets out to find out what happened the night of the fire. After spending some time in the library’s occult section, she tries to explain it to her boyfriend, Chip, like this: Jennifer is “actually evil. Not high-school evil.”

Jennifer’s Body was initially dismissed by most critics as a film lacking “a single good scare” while suffering an “extraordinary dullness” of plot and “eye-rolling obviousness.” Even Roger Ebert, who gave it three stars and conceded that it was “better than it [had] to be,” posited that it was “‘Twilight’ for boys,” a notion derived from Fox’s clumsily marketed sex appeal. But slowly, and especially following the #MeToo movement, Jennifer’s Body gained a new reputation as an overlooked exploration of female friendship and rage, all the more resonant for having been rejected by the same culture that treated an underage Fox like a piece of meat. For angry and abused girls, Jennifer was a symbol of rebellion; her dismemberment of boy after boy was not only cathartic but also funny, triumphant.

When Jennifer, after being violated and discarded by Low Shoulder, resolves to eat the boys in her school, we might think: Good for her. And when Carrie, after being publicly humiliated on prom night, locks her peers in the gymnasium and sets it on fire, we might think the same thing. But at what cost? For all of their might, demonic teen girls can’t easily straighten out the world’s crooked angles. At the end of their stories, Carrie and Jennifer both die, defeated. No justice is restored; their death brings no victory.

Even so, viewers can find gratification in their brief ascent to power. Those of us who remember what it was like to be a teenage girl can recall the fear, confusion, and fury that arise from trying to parse the impossible, unjust parameters the world sets for young women. A reaction that channels this rage into agency, however violent, is immensely seductive. In The Craft, the girls turn to witchcraft in hopes that it will make their lives more bearable, and at first, the ability to exact revenge on their tormentors creates a kind of force field around the coven: Together, they can wield magic as a tool. Sensing that they might get carried away, the older witch from whom they learn their spells tries to warn them about the dangers of abusing magic. But prudence is less alluring than rage, and eventually, Nancy loses control of her own anger.

Yet this violence isn’t justifiable simply because viewers can understand—and even sympathize with—the source of her anger. In fact, the demonic teen girl is more compelling when we refuse to explain away her diabolical acts as righteous. Speaking with The New York Times about Carrie’s 50th anniversary, Cody said that when she wrote Jennifer, she was thinking not of Carrie but of Chris Hargensen, the vicious architect of Carrie’s prom-night humiliation. Chris is beautiful and popular, unlike the reclusive, strange Carrie; telekinesis or not, no one wants to be wretched Carrie. Jennifer’s otherworldly beauty, meanwhile, is not incidental to her character’s power. She has social status, effortless good looks, an implacable demeanor—the sort of image against which most girls measure themselves in adolescence. At that age, who doesn’t want to be Jennifer? It doesn’t matter that she is selfish and possessive of Needy, whose feelings take a back seat to Jennifer’s desire for an “ugly friend”—any hot girl’s indispensable buffer. Needy, for her part, is torn between loving Jennifer, hating her, and wanting to be her.

Unlike Jennifer, Carrie and Nancy are outsiders, and the onset of their supernatural strength brings about a sudden social relevance that changes them for the worse. Carrie becomes a mass murderer, and Nancy turns her coven against one of her less assertive friends. But Jennifer goes through no significant change after turning demonic––another dimension is merely added to her already dominant and callous persona. Interpreting Jennifer’s reign of terror as vindictive is too easy; her choice of prey suggests something different. Of the four boys she kills, two are picked only to spite Needy. Jennifer is not just avenging herself; she is also using her status to diminish Needy, as she always did. Having discovered her best friend in the process of eating her boyfriend, Needy shrewdly asks: “Is it because you’re just really insecure?”

“I’m not insecure, Needy,” Jennifer seethes. “God, that’s a joke. How could I be insecure?” Fox’s brilliant delivery is paired with the look of someone facing the particular shame of having been found out. Jennifer’s social status depends on Needy’s wholesale acceptance of her superiority; the only thing that can shake Jennifer’s confidence is the realization that her advantage won’t last forever. This is one of the shocking lessons of adolescence: that a hot girl can be insecure not because she doesn’t know her worth but precisely because her inflated self-regard is based on the fleeting qualities of beauty and youth.

In the end, Jennifer is sympathetic not because she goes on a boy-killing spree but because, satanic ritual or not, her power is a mirage. That is the popular girl’s cross to bear, and the desperate obstinacy that comes with this realization is one of Cody’s main themes. In her script for Jason Reitman’s 2011 dramedy, Young Adult, Mavis (Charlize Theron), a former high-school queen bee and current trainwreck, returns to her hometown hoping to be validated by her former peers. After hanging out with a guy she considered a loser back in the day and failing to recapture the attention of her former boyfriend, she realizes that her sense of self was built on a foundation made of sand. If Mavis used to be the girl whom every other girl in her school wanted to be, she now cuts a tragic figure. She’s Jennifer, had Jennifer never been sacrificed to the devil.

Beneath the revenge aspect of Jennifer’s rampage lies something infinitely more interesting: a character who is mean, vulnerable, and tough all at once. That, rather than the uncomplicated feeling of “good for her,” is perhaps why Jennifer’s Body endures years on. Though the demonic teen girls might have been terrorizers in life, their bodies end up piled with the bodies of all the women and girls who were victims, rather than perpetrators, of terror. Nancy, Ginger, Carrie, and Jennifer are not exactly villains, but they’re not heroes either—they are, above all else, girls with unforgiving fates.