Attacking the President, Attacking the Nation

5 min read

This is an edition of Time-Travel Thursdays, a journey through The Atlantic’s archives to contextualize the present and surface delightful treasures. Sign up here.

The word assassination summons a universal dread in most Americans. We are not ruled by hereditary monarchs, whose life and death we might witness as mere subjects or bystanders. Instead, in a democracy, we know that “assassination” generally means that someone in our society has killed an elected leader, a fellow citizen we chose through our votes. It’s not part of the normal torrent of politics. It’s not an abstraction. It’s personal. It’s a death in the family—and both the victim and the killer were one of us.

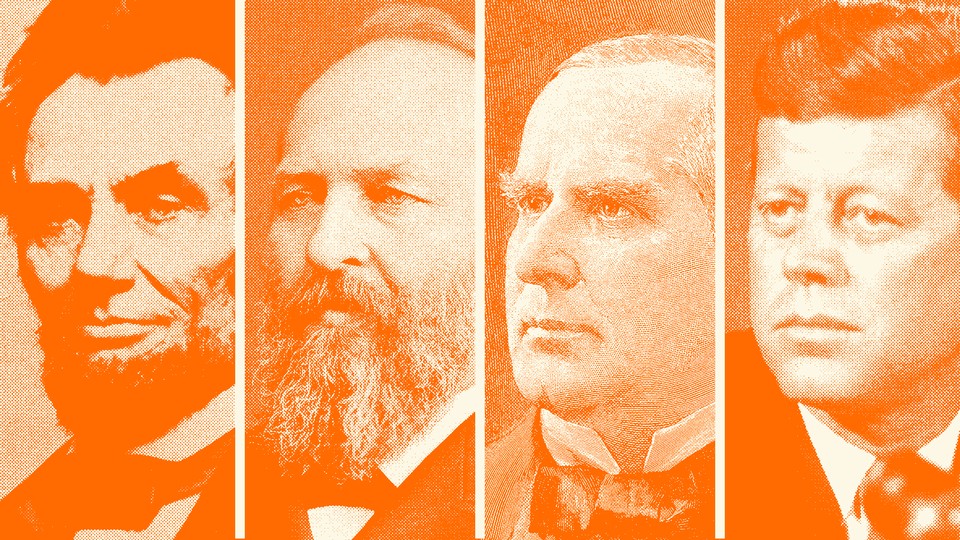

This week, we learned of a possible second attempt to kill former President Donald Trump. Fortunately, the ambush was discovered by the Secret Service, and Trump is unharmed. But the sad truth of American history is that threats against public leaders—and especially against the president, as a symbol of the nation—are common. Some of these threats materialize into actual attacks, and four of them, each taking place in public view, have succeeded in killing the commander in chief.

Writers in The Atlantic have tried throughout our history to make sense of each of these terrible moments. Our archives reflect some of the ways these assassinations have left their scars on the nation.

In 1865, only eight years after The Atlantic was established, Abraham Lincoln was killed in the first successful assassination of an American president since the founding of the republic. (It wasn’t the first attempt on a president’s life: 30 years earlier, an unemployed house painter named Richard Lawrence had taken two shots at Andrew Jackson inside the Capitol, missed both times, and become the first person ever charged in the United States with the attempted assassination of a president.)

The Atlantic was founded as an abolitionist publication, and three months after Lincoln died, the writer Charles Creighton Hazewell expressed cold fury as he peered into the conspiracy against the Union’s leaders. Hazewell (a Rhode Islander, I am now compelled to note as a transplant to the Ocean State) was also unwilling to limit the blame to the now-infamous John Wilkes Booth. “The real murderers of Mr. Lincoln are the men whose action brought about the civil war,” he wrote. “Booth’s deed was a logical proceeding, following strictly from the principles avowed by the Rebels, and in harmony with their course during the last five years.”

Sixteen years would pass before another president was murdered. James Garfield was shot in July 1881, and lingered for weeks. As the wounded president lay on his deathbed, the journalist E. L. Godkin reflected on why the attack on Garfield seemed somehow worse than the killing of President Lincoln. He echoed Hazewell, agreeing that Lincoln’s death seemed like a natural progression in the tragedy of the Civil War, but the shooting of Garfield seemed to come at a time when “the peaceful habit of mind was probably more widely diffused through the country than it had been since the foundation of the government.” (Garfield finally succumbed to his injuries on September 19, 1881—143 years ago today.)

Some assassins believe they will be the movers of great events, but in a prescient comment about Lincoln’s murder, Hazewell noted how the Union’s government continued on after the president’s death: “Anarchy is not so easily brought about as persons of an anarchical turn of mind suppose.” Almost 20 years to the day after Garfield died, however, an anarchist shot President William McKinley after shaking his hand at the Buffalo World’s Fair. Atlantic writer Bliss Perry captured the feeling that would return to Americans during the terrible rash of assassinations in the 1960s, noting that McKinley’s death was the third such murder “within the memory of men who still feel themselves young.”

But Perry’s anguish over McKinley’s murder was tempered by the most American of political emotions: patriotic optimism. “The assault upon democratic institutions has strengthened the popular loyalty to them,” he wrote. “A sane hope in the future of the United States was never more fully justified than at this hour.”

We are an older nation now, and less prone to such faith and exuberance. (And that is to our shame.) Over the next half century, assassins would try to kill Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Harry Truman. For all the grief Perry expressed in 1901, however, Americans had yet to experience the shock of seeing John F. Kennedy slain in a car next to his wife, a video reel apparently destined to be played each November over and over for all time. In early 1964, the historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote a eulogy in The Atlantic for JFK. Morrison had known Kennedy, and his remembrance is a personal one. Perry said of McKinley that the “hour of a statesman’s death is never the day of judgment of his services to his country,” but Morison lauded Kennedy’s personality and achievements, perhaps as comfort to a grieving nation. “With his death,” Morison concluded, “something died in each one of us; yet something of him will live in us forever.”

Public service in an open society should never be a risk, but the reality—especially now, in an age of treating politicians as celebrities—is that our national leaders must always be protected from those among us who are nursing grudges, harboring delusions, and indulging visions of grandeur. The history of assassinations, in America or anywhere else, shows that such attacks are difficult to stop. But rather than surrender to despair, we can return to these writers who tried to make sense of tragedy, and we can resolve, like them, that the bullets of would-be assassins will never kill our faith in the American idea.