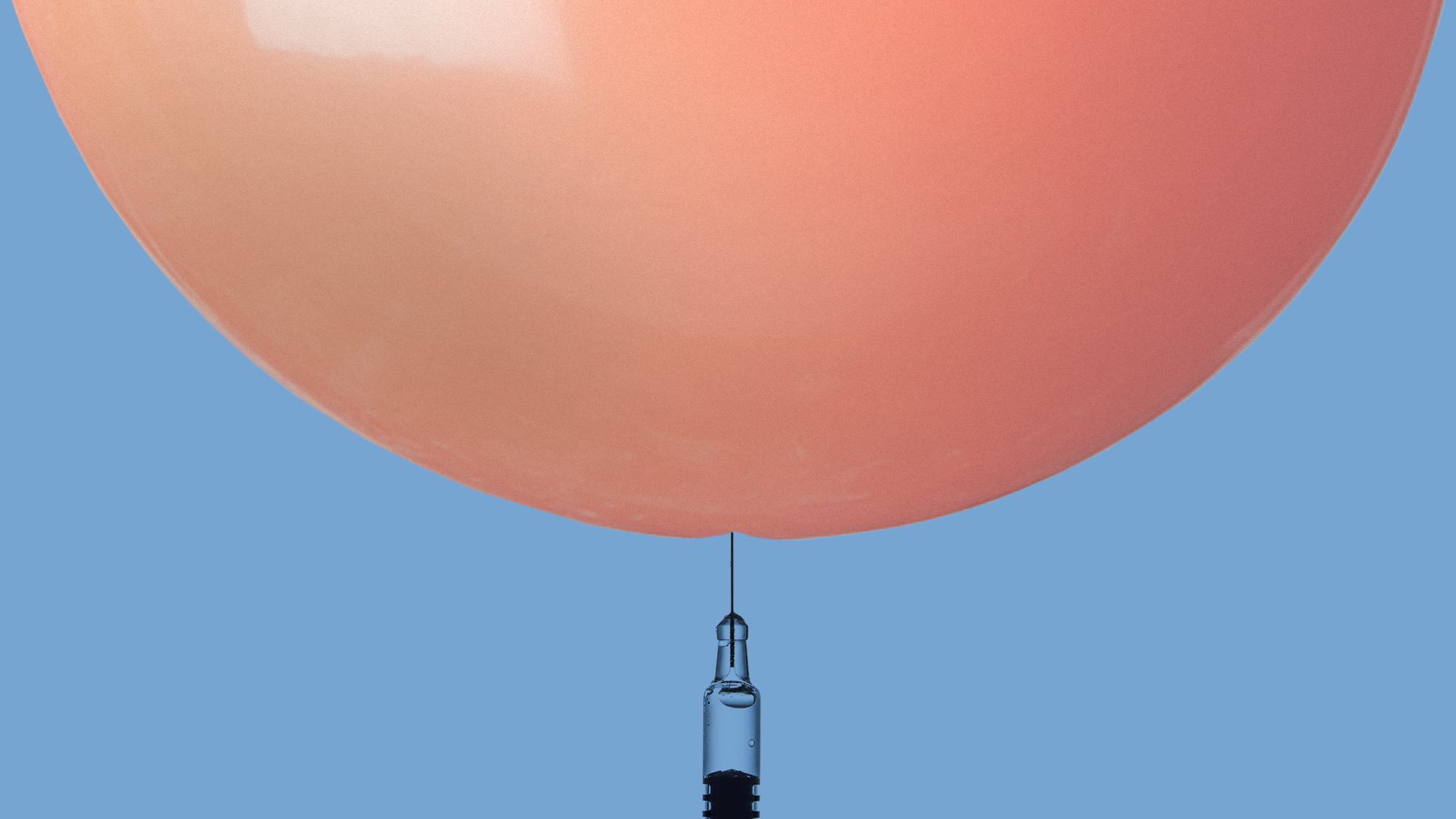

331 Days of Failure

6 min read

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

For a new feature article, my colleague Franklin Foer interviewed two dozen participants at the highest levels of governments in both the U.S. and the Middle East to recount how “11 months of earnest, energetic diplomacy” have so far ended in chaos. Since Hamas’s October 7 attack on Israel, the U.S. administration has managed to forestall a regional expansion of the war, but it has not yet found a way to release all the hostages, bring a stop to the fighting, or salvage a broader peace deal in the region. “That makes this history an anatomy of a failure,” Frank writes: “the story of an overextended superpower and its aging president, unable to exert themselves decisively in a moment of crisis.”

I spoke with Frank about how the core instincts of both President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu have come into play over these past 11 months, what most surprised him in his reporting, and what some Americans misunderstand about their country’s priorities in the Middle East.

331 Days

Isabel Fattal: Tell me a little about how you started working on this story.

Frank Foer: In February and March, I heard about certain instances in which the region had come to the brink of all-out war before things de-escalated. I heard about how, on October 11, Israel almost mistook a flock of birds for paragliders drifting in from Lebanon. It was just this narrowest escape, and I started asking about that story and whether there were other similar incidents over the past 11 months.

Isabel: Something that struck me reading your reporting is how the ingrained instincts and worldviews of both Netanyahu and Biden have influenced policy outcomes at every turn. In what ways did you see Netanyahu’s particular instincts show up?

Frank: Netanyahu would love nothing more than to have Israel normalize relations with Saudi Arabia, and I think he would like to get the hostages home at the end of the day. But not only is his own political situation somewhat tenuous—he has this almost characterological aversion to making the most difficult decisions. When it comes time for him to make hard choices, he reverts to negotiating and negotiating and negotiating and never really settling on an actual policy or solution. He ends up dragging things out.

There’s some ways in which this places him to the left of a lot of the other people in the room on questions about confronting Hezbollah or Iran. He’s oftentimes the voice pleading for restraint or saying, We need to make sure that we have our American allies with us. I think he was to the left of other people in his cabinet about letting humanitarian aid into Gaza. But he was unwilling to have a massive confrontation with his coalition partners over that. And so he became a source of incredible frustration to Joe Biden. Biden wasn’t naive about Netanyahu, but I think he expected reciprocity—that at some point Netanyahu would take a political hit on his behalf in the same sort of way that Biden was taking political hits on Netanyahu’s behalf. Biden has a code of morality that’s all about generosity and reciprocity, and he expects that in return.

Isabel: You write about Biden being able to remember the dawn of the atomic age, and how fear of escalation has animated his decision making. Of course, that’s nothing new for an American president. But does Biden operate from that place of fear in a way that’s distinct from other American leaders?

Frank: I think he’s got this very singular combination of a willingness to do bold things, and then this other side that is filled with excessive prudence. This was obvious in Ukraine, where he sent them lots of arms and stood with them in a way that I don’t think many other American presidents would have. But for a long time, he also put hard brakes on Ukraine when they wanted to strike within Russia. He’s done a little bit of the same thing here. There were moments where it seemed inevitable that Israel was going to have a military confrontation with Hezbollah. And he asked them to pull back because he was afraid that everything could go up in flames in the Middle East. That’s a very reasonable position for a president of the United States to take, because the consequences of a regional war are so extreme.

Isabel: It seems like when Americans talk about America’s interests and priorities in this war, they can sometimes forget the major role that the threat of all-out regional conflict plays.

Frank: Absolutely. One of the things that I learned reporting this story was the extent to which Saudi Arabia’s place within the Middle East and within the global economy was one of the things that drives a lot of America’s Middle East policy. We’ve been worried that Saudi Arabia could drift into China’s economic sphere, and we’ve been trying to build a regional coalition of allies to contain Iran. Plus, we wanted to have a tight economic relationship with Saudi Arabia. That became a pillar of Biden-administration policy, even though Biden came to office after the Khashoggi assassination and intended to punish Saudi Arabia. He’s walked a long way from that.

Isabel: What most surprised you in reporting this story?

Frank: The fact that Biden was against the Israeli invasion of Gaza at the beginning, just after October 7, in the form that it took place—that he had a different vision for what the war would look like. It was really far removed from the Israeli vision. That was a suppressed source of friction; both sides were worried about how Israel’s enemies would exploit any perceived disagreements between the U.S. and Israel. But that was the first real source of tension between the Biden administration and the Israelis.

Read Frank’s full exploration here.

Here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- David Frum: Trump’s Mob-boss warning to American Jews

- Republicans are finally tired of shutting down the government.

- Why Trump is trying to to erase his presidency

Today’s News

- Israel is considering a ground invasion of Lebanon, according to the Israeli military’s chief of staff. U.S. officials said that they are working to avoid an all-out war between Israel and Hezbollah.

- The House passed a short-term funding bill, which the Senate will also need to pass to avert a government shutdown next week.

- In a speech to the United Nations, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said that Russia is planning on carrying out strikes on Ukraine’s nuclear-power plants.

Evening Read

The Logical Extreme of Anti-aging

By Yasmin Tayag

Something weird is happening on my Instagram feed. Between posts of celebrities with perfect skin are pictures of regular people—my own friends!—looking just as good. They’re in their mid-30s, yet their faces look so smooth, so taut and placid, that they look a full decade younger. Is it makeup? Serums? Supplements? Sleep? When I finally inquired as to how they’d pulled it off, they gladly offered an explanation: “baby Botox.”

Read the full article.

More From The Atlantic

- A simple lab ingredient derailed science experiments.

- Oren Cass: Trump’s most misunderstood policy proposal

Culture Break

Debate. Is Katy Perry stuck in a musical rut? Though she’s never been known as a bold and forward-thinking artist, her latest album, 143, sounds like the light has gone out, Spencer Kornhaber writes.

Reimagine celebrations. Many Latina women hitting 50 aren’t just throwing a big party—they’re determined to redefine what it means to age, Valerie Trapp writes.

Play our daily crossword.

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.