Israel Tries for a Knockout Blow

6 min read

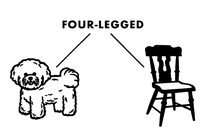

As a teenager, I took boxing lessons. What I learned from that experience—and I commend a bit of pugilistic training to all budding civilian strategists—is that you can take a punch and keep on going. But if your opponent can fire off a combination that connects—jab, jab, jab, cross, hook—you begin staggering, and then the blows will keep raining down until the coach calls an end to the round, or you throw in the towel.

That is what the Israelis have done to Hezbollah over the past two months. First they killed Fuad Shukr, the top military commander of the Lebanese militia. Then they detonated thousands of pagers used by its members. Next they exploded walkie-talkies. Then they launched hundreds of sorties, targeting missile and rocket depots. And now, in the equivalent of a devastating uppercut, they have killed Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, and others who had gathered in its headquarters bunker.

The entire sequence of Israeli military attacks has been misunderstood by those who think that peace is the norm and that, rather than figuring out what a military campaign is intended to do and what its prospects are, they should simply find the quickest way of getting it to stop. It may be uncomfortable, particularly to the Western mind, to take that more detached perspective, but it is necessary.

Israel experienced strategic shock on October 7—that is to say, an unexpected blow. For the next several days, multiple levels of command of the Israel Defense Forces, including the Gaza division, were simply dysfunctional. Because Hamas could not follow up its initial punch, however, the IDF was eventually able to recover.

Hezbollah should not have been taken similarly off guard. On October 8 and in the months since, it chose to fire salvos over the border into Israel, killing civilians as well as soldiers, in order to declare its solidarity with Hamas and take advantage of Israel’s disarray and paralysis. It knew that it was at war with Israel, because it had initiated that war and repeatedly declared it. But since July, it has suffered an operational shock of a kind rarely seen in recent Middle Eastern conflicts—or, indeed, in most wars.

The Israeli strategy was to hit the enemy in different places. With Shukr and his associates they struck a blow at Hezbollah’s leadership, then pressed their attacks with strikes on regional and functional commanders, including the head of Hezbollah’s missile force. The pager and walkie-talkie attacks were a body blow to Hezbollah’s middle management—the people any complex organization needs to operate. The attacks not only disabled them physically; they also undercut their willingness to communicate electronically and, no doubt, shook their faith in the high command that distributed ticking bombs to its subordinates. The campaign of air strikes that followed, as scenes of secondary explosions suggest, smashed up key parts of Hezbollah’s arsenal, and the latest, devastating blow was aimed at removing its leader of 32 years, as well as some of his key aides.

Hezbollah has struggled to retaliate, despite its prewar inventory of an estimated 150,000 or more missiles and rockets. A military organization battered in so many places will simply find it hard to do all the kinds of things—planning, coordinating, moving people and munitions—needed to fight a big battle.

For Iran the shock is strategic: It may have just lost, for a considerable period of time, its most important proxy force. And the effects will ripple out. The Houthis in Yemen, and Iraqi and Syrian militias sponsored by the Iranians, must now wonder whether their allies in Tehran will do anything for them if Israel or the United States comes after them. They may worry as well about their communications systems. And Hamas may reach the conclusion that no external force is capable of expanding the war it launched on October 7.

The lessons for the United States are useful. Once again, our government and most of our interpreters of events have shown themselves unable to understand war on its own terms, having instead been preoccupied by their commendable focus on humanitarian concerns and their understandable interest in ending the immediate hostilities. Israel has repeatedly acted first and explained later, and for a strategically understandable reason: It does not want to get reined in by a patron that may understand with its head the need for decisive operations in an existential war, but does not get it in its gut. In the same way that the United States government says that it is with Ukraine “as long as it takes” but cannot bring itself to use words like victory, much less to give Kyiv the full-throated military support that it needs, Israel’s undoubtedly indispensable ally has given it to mistrust it, too. And so it acts.

The Israelis believe, with reason, that diminishing civilian suffering today by a sudden cease-fire will only make another, more destructive war inevitable, with losses to populations on both sides that dwarf those seen thus far. Up against opponents who deliberately place headquarters, arms depots, and combatants among—and under—a civilian population, the Israelis will wait in vain for an explanation of how one fights such enemies without killing and wounding civilians. They will wait in vain too, in most cases, for more than formulaic regret from most quarters about the displacement, maiming, and death of Israeli civilians.

Genuinely good intentions and reasonableness are inadequate in the face of real war. The United States government was surprised by the swift and bloody collapse of Afghanistan when American forces withdrew. But anyone who had given thought to the role of morale in war should have expected as much. U.S. leaders did not expect Ukraine to survive the Russian onslaught in February 2022, which reflected even deeper failures of military understanding. They continue to be trapped by theories of escalation born of the Cold War and irrelevant to Ukraine’s and Russia’s current predicament. While denying Ukraine the long-range weapons it needs, and permission to use those it has, they have decried Ukraine’s failure to offer a convincing theory of victory, which surely depends on such arms. In Israel’s war with Hamas, they tried to block the sort of difficult, destructive operations, such as the incursion into Rafah, that have proved necessary to shatter Hamas as a military organization. And when Israel struck this series of blows at Hezbollah they have, with the best intentions in the world, attempted to stop operations that are the inevitable consequence of real war.

That is what Israel, like Ukraine, is waging: real war. While the consequences of neither ally’s operations are foreseeable, both understand an essential fact memorably articulated by Winston Churchill:

Battles are the principal milestones in secular history. Modern opinion resents this uninspiring truth, and historians often treat the decisions of the field as incidents in the dramas of politics and diplomacy. But great battles, won or lost, change the entire course of events, create new standards of values, new moods, new atmospheres, in armies and in nations, to which all must conform.

Much foreign-policy discourse in the United States and Europe rests on the unstated assumption that diplomacy is an alternative to the use of military force. In real war, it is the handmaiden of it. There may be an opportunity here for diplomacy to change the geopolitics of the Levant and perhaps beyond, thanks to decisive Israeli action, as there most likely would be in Europe if Ukraine were armed to the extent and depth that it needs. But that can only happen if we realize that, whether we wish it or not, we are again in the world of war, which plays by rules closer to those of the boxing ring than the seminar room.