The Lessons of Aging

5 min read

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Over the past few months, I’ve found myself thinking a lot about old age. Earlier this year, imost Americans seemed to share my fixation, as voters debated President Joe Biden’s mental fitness for a second term. But my preoccupation also has something to do with realizing that my peers—those in their early 30s—are no longer the primary audience for pop culture, as well as the feeling that people close to me are no longer “getting older” every year, but actually “aging.” And because you’re reading the Books Briefing, it won’t be a surprise that I’ve turned to literature for guidance.

First, here are four stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- A naked desperation to be seen

- In defense of marital secrets

- Six books that feel like watching a movie

- The woman who would be Steinbeck

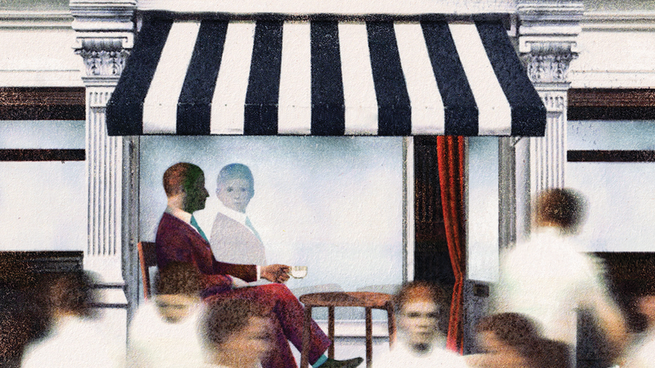

With his latest novel, Our Evenings, the English author Alan Hollinghurst, now 70 years old, has written a work that “reads like a throwback,” Charles McGrath wrote for us this week: It is “as if the author, now older and wiser, were reminding both himself and his readers that … true emotional intimacy is often elusive.” Like all of Hollinghurst’s work, McGrath argues, his latest is focused on “time, and what it does to everything.” And what the passing years seem to do, most of all, is get in the way of the truth: Many of Hollinghurst’s characters intentionally misremember or obscure their past mistakes and failures. A vein of sadness runs through the novel; the “evenings” of the title perhaps refers not only to the protagonist’s numbered days but also to a bygone era in England, and a romanticized past that was simpler than “the mess that contemporary Britain has become,” as McGrath puts it.

The writer Lore Segal, who died this week at the age of 96, had a somewhat different approach to the passage of time—one with more humor and less regret. The Austrian American author was best known for her tales about immigrants and outcasts; last year, my colleague Gal Beckerman recommended her novel Her First American for our summer reading guide, writing that “the originality of this love story between two outsiders in 1950s New York City … cannot be overstated.” And Segal kept writing until the very end of her life. In James Marcus’s appreciation of her life and work, he writes that in recent years she sent him drafts of her new stories, many of which were included in her final collection, Ladies’ Lunch. Even after a decades-long career, Segal was “still beset with doubts about her work,” Marcus reports.

Her last story for The New Yorker, to which she was a frequent contributor, was published just last month. In it, the reader sees Segal address those doubts almost head-on. The story follows a group of old friends who get together and, almost immediately, start talking about the embarrassment of writing for a living. Bridget mentions that she’s sent her latest story to a friend from a former writing class, and for four weeks, she’s been anxiously awaiting a response. The others ask what she’ll do, and she responds that she’ll “lie in bed at night and stew. Dream vengeful dreams.” Age, it seems, doesn’t dissipate pettiness or insecurity.

In that story, which appeared in Ladies’ Lunch, Segal doesn’t betray much sadness at getting older, just a commitment to working things out on the page. Where Hollinghurst’s work is tinged with regret over unfulfilled lives and better days, Segal looks back with a less maudlin touch. She seems to suggest that the solution to aging is to just keep living—and writing.

Alan Hollinghurst’s Lost England

By Charles McGrath

In his new novel, the present isn’t much better than the past—and it’s a lot less sexy.

Read the full article.

What to Read

Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso

Almost no one is writing like Drnaso, whose second book, Sabrina, became the first graphic novel to be nominated for the Booker Prize, in 2018. The story, which explores the exploitative nature of both true crime and the 24-hour news cycle, focuses on a woman named Sabrina who goes missing, leaving her loved ones to hope, pray, and worry. When a video of her murder goes viral on social media, those close to her get sucked into supporting roles in strangers’ conspiracy theories. Drnaso’s style across all of his works—but especially in Sabrina—is stark and minimal: His illustrations are deceptively simple, yet entrancing. He doesn’t overload the book with dialogue. He knows and trusts his readers to put the pieces together; part of the audience’s job is to conjure how his characters feel as they approach the mystery of Sabrina’s disappearance and death. Drnaso wants to show the reader how, in a society full of misinformation and wild suppositions, the most trustworthy resource might just be your own two eyes. — Fran Hoepfner

From our list: Six books that feel like watching a movie

Out Next Week

📚 An Image of My Name Enters America, by Lucy Ives

📚 Valley So Low, by Jared Sullivan

📚 Don’t Be a Stranger, by Susan Minot

Your Weekend Read

Melania Really Doesn’t Care

By Sophie Gilbert

What is she thinking? First ladies, by the cursed nature of the role, are supposed to humanize and soften the jagged, ugly edge of power. The job is to be maternal, quietly decorative, fascinating but not frivolous, busy but not bold. In some ways, Melania Trump—elegant, enigmatic, and apparently unambitious—arrived in Washington better suited to the office than any other presidential spouse in recent memory. In reality, she ended up feeling like a void—a literal absence from the White House for the first months of Donald Trump’s presidency—that left so much room for projection. When she seemed to glower at her husband’s back on Inauguration Day, some decided that she was desperate for an exit, prompting the #FreeMelania hashtag. When she wore a vibrant-pink pussy-bow blouse to a presidential debate mere days after the Access Hollywood tape leaked, the garment was interpreted by some as a statement of solidarity with women, and by others as a defiant middle finger to his critics. Most notoriously, during the months in 2018 when the Trump administration removed more than 5,000 babies and children from their parents at the U.S. border, Melania wore a jacket emblazoned with the words I REALLY DON’T CARE, DO U? on the plane to visit some of those children, the discourse over which rivaled the scrutiny of one of the cruelest American policies of the modern era.

Read the full article.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.