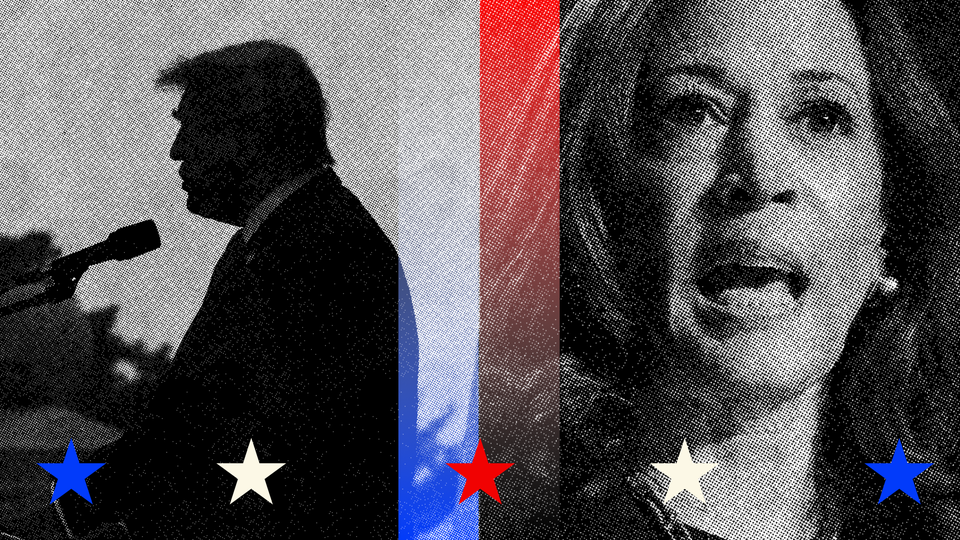

Kamala Harris’s Closing Argument

11 min read

Kamala Harris’s fate in the remaining weeks of the presidential campaign may turn on whether she can shift the attention of enough voters back to what they might fear from a potential second White House term for Donald Trump.

Since replacing President Joe Biden as the Democratic nominee this summer, Harris has focused her campaign message above all on reassuring voters that she has the experience and values to serve in the Oval Office. But a consensus is growing among Democratic political professionals that Harris is failing to deliver a sufficiently urgent warning about the risk Trump could pose to American society and democracy in another presidential term.

“Reassurance ain’t gonna be what wins the race,” the Democratic pollster Paul Maslin told me—an assessment almost universally shared among the wide array of Democratic strategists and operatives I’ve spoken with in recent days. “What wins the race is the line from the convention: We ain’t going back. We aren’t going to live with this insanity again. It has to be more personal, on him: The man presents risks that this country cannot afford to take.”

Harris aides insist that she and the campaign have never lost sight of the need to keep making voters aware of the dangers inherent in her opponent’s agenda. But she appears now to be recalibrating the balance in her messaging between reassurance and risk.

At a rally in Erie, Pennsylvania, on Monday night, Harris had a video clip play of some of Trump’s most extreme declarations—including his insistence in a Fox interview on Sunday that he would use the National Guard or the U.S. military against what he called “the enemy from within.” Then, in stark language, she warned: “Donald Trump is increasingly unstable and unhinged, and he is out for unchecked power.” In her combative interview on Fox News last night, Harris again expressed outrage about Trump’s indication that he would use the military against “the enemy from within,” accurately pushing back against Bret Baier and the network for sanitizing a clip of Trump’s reaffirmation of that threat at a Fox town-hall broadcast earlier in the day.

Many Democratic strategists believe that the party has performed best in the Trump era when it has successfully kept the voters in its coalition focused on the risks he presents to their rights and values—and his latest threat to use the military against protesters is exactly one such risk to them. Using data from the Democratic targeting firm Catalist, the Democratic strategist Michael Podhorzer has calculated that about 91 million different people have come out in the four elections since 2016 to vote against Trump or Republicans, considerably more than the 83 million who have come out to vote for him or GOP candidates. To Podhorzer, the vital question as Election Day looms is whether the infrequent voters in this “anti-MAGA majority” will feel enough sense of urgency to turn out again.

“The reason [the race] is as close as it is right now is because there’s just not enough alarm in the electorate about a second Trump term,” Podhorzer, who was formerly the political director of the AFL-CIO, told me, “and that’s what is most alarming to me.”

Harris is pivoting toward a sharper message about Trump at a moment when his campaign appears to have seized the initiative in the battleground states with his withering and unrelenting attacks on her. National polls remain mostly encouraging for Harris; several of them showed a slight tick upward in her support this week. But Republicans believe that after a weeks-long barrage of ads portraying Harris as weak on crime and immigration and extreme on transgender rights, swing voters in these decisive states are inclined to see her, rather than Trump, as the greater risk in the White House.

Although Harris is describing Trump as “unstable,” Jim McLaughlin, a pollster for his campaign, says that at this point more voters see him, over her, as a potential source of stability amid concerns that inflation, crime, the southern border, and international relations have at times seemed out of control under Biden. “They think [Trump] is the one who will give us that peace and prosperity they look for in a president,” McLaughlin told me. “They want somebody who is going to take charge and solve their problems, and that’s what Donald Trump is really good at.”

Democrats are not worried that large numbers of voters outside Trump’s base will ever see him as a source of stability. But they acknowledge that the Republican ad fusillade—particularly the messages about Harris’s support, during her 2019 presidential campaign, for gender-conforming surgery for prisoners—has caused some swing-state voters to focus more on their worries about her (that she’s too liberal or inexperienced) than their fears about Trump (that he’s too erratic, belligerent, or threatening to the rule of law).

The clearest measure that voters’ concerns about a second Trump presidency are receding may be their improving assessments of his first term. A Wall Street Journal poll conducted by a bipartisan polling team and released late last week found that Trump’s retrospective job-approval rating had reached 50 percent or higher in six of the seven battleground states, and stood at 48 percent in the seventh, Arizona.

An NBC poll released on Sunday, which was conducted by another bipartisan polling team, found that 48 percent of voters nationwide now retrospectively approve of Trump’s performance as president; that rating was higher than the same survey ever recorded for Trump while he was in office. A Marquette Law School national poll released yesterday similarly showed his retrospective job approval reaching 50 percent. (Trump was famously the only president in the history of Gallup polling whose approval rating never reached 50 percent during his tenure.)

Views about Trump’s first term are improving, pollsters in both parties say, because voters are mostly measuring him against what they like least about Biden’s presidency, primarily inflation and years of disorder on the southern border (though it has notably calmed in recent months). “Trump’s retrospective job rating is higher because of the contrast with Biden,” Bill McInturff, a longtime Republican pollster who worked on the NBC survey, told me. “Majorities say the Biden administration has been a failure. A plurality say Biden’s policies hurt them and their families, while Trump’s policies helped them.”

Harris could still win despite voters becoming more bullish about Trump’s first term, but it won’t be easy: The NBC poll found that, in every major demographic group, the share of voters supporting Trump against Harris almost exactly equals the share that now approves of his performance as president.

Because of the unusual circumstances in which Harris secured her party’s nomination, voters probably knew less about her at that advanced stage in the presidential campaign season than they did about any major-party nominee since Republicans plucked the little-known business executive Wendell Willkie to run against Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940. Few political professionals dispute that her late entry required her campaign to devote much of its initial effort to introducing her to voters.

In her speeches, media appearances, and advertising, Harris has placed most emphasis on convincing voters that she is qualified to serve as president, tough enough on crime and the border to keep them safe, committed to supporting the middle class because she comes from it, and determined to govern in a centrist, bipartisan fashion. This sustained effort has yielded important political dividends for her in a very short period. Polls have consistently showed that the share of Americans with a favorable view of her has significantly increased since she replaced Biden as the nominee. Harris has gained on other important personal measures as well. A recent national Gallup poll found that she has drawn level with Trump on the qualities of displaying good judgment in a crisis and managing the government effectively. Gallup also found that she has outstripped him on moral character, honesty, likability, and caring about voters’ needs.

The question more Democrats are asking is whether Harris has squeezed as much advantage as she can out of this positive messaging about her own qualifications. That question seemed especially acute after she raced through a swarm of media interviews earlier this month, appearing on podcasts aimed at young women and Black men, as well as on The View, 60 Minutes, CBS’s The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, and a Univision town hall.

Across those interviews, Harris seemed determined to establish her personal “relatability,” demonstrating to voters, especially women, that she had lived through experiences similar to their own and understood what it would take to improve their lives. But she offered no sense of heightened alarm about what a second Trump term could mean for each of the constituencies that her appearances targeted.

One Democratic strategist, who is closely watching the campaign’s deliberations and requested anonymity to speak freely, worries that Harris has not been airing a direct response to Trump’s brutal ad attacking her position on transgender rights, or pressing the case against him aggressively enough on what a second Trump term might mean. “We’ve been trying to fight this negative onslaught with these positive ads,” this strategist told me. “We’re bringing the proverbial squirt gun to the firefight here in terms of how we are dealing with the most vicious negative ad campaign in presidential history.”

Harris’semphasis on reassurance has also shaped how she’s approached the policy debate with Trump. Her determination to display toughness on the border has, as I’ve written, discouraged her from challenging Trump on arguably the most extreme proposal of his entire campaign: his plan for the mass deportation of an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants.

Likewise, her determination to stress her tough-on-crime credentials has apparently discouraged her from challenging another of Trump’s most draconian plans: his pledge to require every U.S. police department to implement so-called stop-and-frisk policies as a condition of receiving federal law-enforcement aid. In New York City, that policy was eventually declared unconstitutional because it resulted in police stopping many young Black and Latino men without cause. Yet, for weeks, Harris never mentioned Trump’s proposal, even in appearances aimed at Black audiences.

“For low-propensity Black voters, Donald Trump’s just atrocious policy proposals for the civil rights agenda and policing is one of the main motivators that moves them toward the Democrats,” Alvin Tillery, a Northwestern University professor who founded a PAC targeting Black swing voters, told me. “Forget Bidenomics, forget all the kind of race-neutral things she is trotting out today. Mentoring for Black men? Really? That is not going to move a 21-year-old guy that works at Target who is thinking about staying home or voting for her to get off the couch.” Tillery’s PAC, the Alliance for Black Equality, is running digital ads showing young Black men and women lamenting the impact that stop-and-frisk could have on them, but he’s operating on a shoestring budget.

More broadly, some Democrats worry that Harris’s priority on attracting Republican-leaning voters cool to Trump has somewhat dulled her messages about the threat posed by the Trump-era GOP. Harris has repeatedly offered outreach and reassurance to GOP-leaning voters, by promising, for example, to put a Republican in her Cabinet and establish a policy advisory council that will include Republicans. (She held another rally in the Philadelphia suburbs yesterday to tout her Republican support.) That could help her win more of the Nikki Haley–type suburban moderates—but at the price of diluting the sense of threat necessary to motivate irregular anti-Trump voters to turn out.

“I do think some sacrifices have been made in the spirit of trying to win over a certain segment of voter, who is a Republican,” Jenifer Fernandez Ancona, a senior vice president at Way to Win, a group that provides funding for candidates and organizations focused on mobilizing minority voters, told me.

The Republican pollster Greg Strimple told me that last month’s presidential debate hurt Trump so much not only because Harris was strong, but also because his scattered and belligerent performance reminded voters of everything they didn’t like about him in office. “Now it feels to me like her momentum is gone, and Trump is steadily advancing, almost like the Russian army, in the center of the electorate,” Strimple told me. “I don’t know how she can muster enough throw weight behind her message in order to change that dynamic right now.”

Even among the most anxious Democrats I spoke with, hardly anyone believes that Harris’s situation is so dire or settled. They were widely confident that she possesses a superior get-out-the-vote operation that can lift her at the margin in the pivotal battlegrounds, particularly Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Still, Harris this week seemed to acknowledge that she needs to sharpen her message about Trump. In an interview with the radio host Roland Martin, she forcefully denounced Trump’s long record of bigoted behavior. With Charlamagne tha God, Harris came out of the gate criticizing Trump’s stop-and-frisk mandate more forcefully than I’ve heard before, and condemning the former president for, as Bob Woodward reported in a new book, sending COVID-19 test kits to Vladimir Putin “when Black people were dying every day by the hundreds during that time.” Later, she agreed with the host when he described Trump’s language and behavior as fascist, a line she had not previously crossed.

Harris’s campaign also rolled out a new ad that also highlighted his comments about deploying the military against the “enemy from within,” and featured Olivia Troye, an aide in his administration, speaking on camera about how he’d discussed shooting American citizens participating in protests when he was president.

McLaughlin, the Trump pollster, says a big obstacle for Democrats trying to stoke fears of returning him to the White House is that voters have such an immediate point of comparison between their economic experiences in his tenure and Biden’s. Democrats “can try” to present another Trump term as too risky, but to voters, “what is it going to mean?” McLaughlin said. “I’m going to be able to afford a house because, instead of 8 percent mortgage rates, I’m going to have less than 3 percent? I’m going to have a secure border?”

Like many Democratic strategists, Fernandez Ancona believes that enough voters can be persuaded to look beyond their memories of cheaper groceries and gas to reject all the other implications of another Trump presidency. That dynamic, she points out, isn’t theoretical: It’s exactly what happened in 2022, when Democrats ran unexpectedly well, especially in the swing states, despite widespread economic dissatisfaction.

“If the question in 2022 was: Do you like the Biden administration and the state of the economy? We lose,” she told me. “But that wasn’t the question people were responding to. They were responding to: Your freedoms are at stake, do you want to protect your freedoms or do you want them taken away?”

Democratic voters are understandably dumbfounded that Trump could remain this competitive after the January 6 insurrection; his felony indictments and convictions; the civil judgments against him for sexual abuse and financial fraud; the strange lapses in memory, desultory tangents, and episodes of confusion at rallies; and his embrace of more openly racist, xenophobic, and authoritarian language. Yet nearly as remarkable may be that Harris is this competitive when so many more voters consistently say in polls that they were helped more by the policies of the Trump administration than those of the Biden administration in which she has served.

The definitive question in the final stretch of this painfully close campaign may be which of those offsetting vulnerabilities looms larger for the final few voters deciding between Harris and Trump or deciding whether to vote at all. Nothing may be more important for Harris in the remaining days than convincing voters who are disappointed with the past four years of Biden’s tenure that returning Trump to power poses risks the country should not take. As a former prosecutor, Harris more than most candidates should understand the importance of a compelling closing argument.