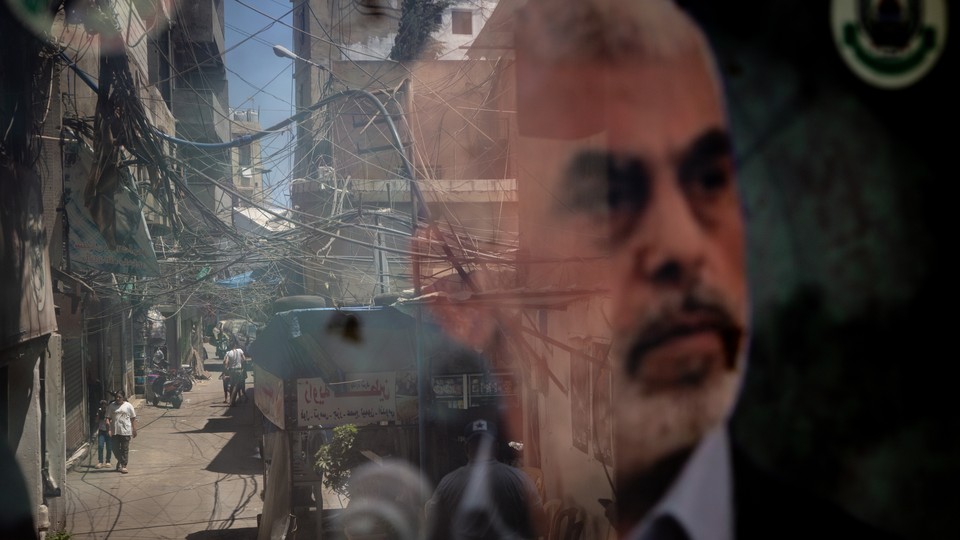

Sinwar’s Death Changes Nothing

5 min read

The killing on Thursday of the Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, the principal architect of the October 7 attack on southern Israel, offers a golden opportunity for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to declare victory and begin pulling troops out of Gaza. But that is not going to happen. Most likely, nothing will change, because neither Netanyahu nor Hamas wants it to.

Netanyahu’s calculation is no mystery. Should he leave political office, he faces a criminal-corruption trial and a probable inquiry into the security meltdown on October 7. He has apparently concluded that the best way to stay out of prison is to stay in power, and the best way to stay in power is to keep the war going—specifically, the war in Gaza. The battle against Hezbollah in Lebanon is too volatile, and involves too many other actors, including the United States, Iran, and Gulf Arab countries, for Israel to keep control of its trajectory. For this reason, Lebanon is much less useful than Gaza as a domestic political tool.

For Israel, the war in Gaza has become a counterinsurgency campaign with limited losses day to day. This level of conflict likely seems manageable for the short term, and appears beneficial to Netanyahu. Hamas, for its part, seems to think it can hold out in the short term, and gain in the long term. An insurgency requires little sophistication by way of organizational structure or weaponry—only automatic rifles, crude IEDs, and fighters who are prepared to die. Years, possibly a decade or longer, of battles against Israeli occupation forces for control of Palestinian land in Gaza are intended to elevate the Hamas Islamists over the secular-nationalist Fatah party as the nation’s bloodied standard-bearer. Hamas leaders may well see no reason to abandon this path to political power just because Sinwar is dead.

Some more moderate members of the Qatar-based Hamas politburo, such as Moussa Abu Marzouk, have expressed discomfort with the October 7 attack and Sinwar’s “permanent warfare” strategy. But they are not likely to prevail over more hard-line counterparts, such as the former Hamas leader and ardent Muslim Brotherhood ideologue Khaled Mashal (some sources are already reporting that he has been named to succeed Sinwar). The truth is that none of these exiled politicians may wind up exerting much control over events on the ground in Gaza. Sinwar, who was himself a gunman and served time in an Israeli prison, once derided them as “hotel guys” because of their relatively plush accommodations in Qatar, Turkey, and Lebanon. Real power flowed to military leaders such as himself.

Sinwar effectively controlled Hamas starting from 2017 at the latest, even though Ismail Haniyeh, based in Qatar, was the group’s official chairman. Only after Israel assassinated Haniyeh in Tehran on July 31 did Sinwar formally become the leader that he had long actually been. Today, fighters such as Sinwar’s younger brother Mohamed, the commander of the southern brigade, and Izz al-Din Haddad, the commander in northern Gaza, are ready to step into the leadership role with or without official titles. The political figureheads in Qatar will most likely continue to do what they’ve done for at least the past decade, serving mainly as diplomats, tasked with securing money and arms, as well as defending and promoting Hamas policies on television.

The only scenario in which Sinwar’s death would lead the “hotel guys” to gain real authority instead of these fighters would be if the group’s remaining leadership cadres decided that Hamas should stand down long enough to rebuild. This could be a tactical pause; it could also be a strategic decision, if the group finds itself so exhausted that it prefers making a deal to continuing an insurgency that could take many years to achieve its political purpose. In either of these scenarios, Hamas would be looking above all for reconstruction aid—which would give the exiled leaders, who are best placed to secure such aid, leverage over the militants on the ground.

But these are not likely outcomes. The Hamas insurgency was gaining momentum before Sinwar’s death, and Israel was poised to impose a draconian siege on northern Gaza in response. Nothing suggests that Israeli leaders are closer to recognizing what a counterinsurgency campaign will really entail—and that such efforts tend to become quagmires, because they don’t usually yield a decisive victory, and withdrawing without one will look like capitulation, whether it happens now or in several years.

That’s why the death of Sinwar offers such an important inflection point for Israel. It’s an opportunity to end a conflict that otherwise threatens to go on indefinitely. But the history of this war is dispiriting in this regard: Israel has already squandered just such an inflection point earlier this year.

That chance came when the Israel Defense Forces overran Rafah, the southernmost town in Gaza, in stages from May to August. For almost a year, the Israeli military had smashed its way through the Gaza Strip from north to south, destroying everything it considered of value to Hamas, including much of what was indispensable for sustaining its 2.2 million Palestinian residents. Now the IDF had effectively reached the Egyptian border. No more obvious Hamas assets remained, at least aboveground.

Israel could have declared Hamas defeated and made a near-complete withdrawal contingent on the release of all remaining hostages—a deal that Hamas appears to have been willing to take in the past, and which public sentiment in Gaza would have rendered politically devastating to reject. Hamas would have surely crawled out of its tunnels and declared a pyrrhic victory of its own. But the group would then own the devastation of its realm, and with Israel gone, ordinary Palestinians would have a chance to reckon with Hamas’s decision to sign 2.2 million of them up for martyrdom without any consultation.

Instead, Israel chose to remain in Gaza, becoming the inevitable focus of Palestinian anger and terror.

Open-ended conflict is certainly what Sinwar wanted. It’s evidently what Netanyahu wants. And no viable alternative leadership for Hamas or Israel appears to be emerging, nor are critical masses of Israelis or Palestinians demanding an end to the hostilities. Sinwar is gone—but the insurgency he set in motion seems set to live on into the foreseeable future.