The Presidential Campaign That Happened to Pennsylvania

18 min read

An hour’s drive from downtown Pittsburgh is one of the most beautiful places in America—Fallingwater, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s late masterpiece. The house is a mass of right angles, in ochre and Cherokee red, perched above the Bear Run waterfall that provides the house its name.

Fallingwater was commissioned in 1934 by a couple, Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann, whose family had made its fortune from a brick-and-mortar business—a department store in Pittsburgh founded in 1871, when the city was flush with steel and glass money. Edgar became a generous patron of the arts in Pittsburgh and helped raise money for a local arena. Before he bought the Fallingwater site outright, the land had been leased to the store’s employee association, which allowed workers to spend their summers there.

Unlike today’s rich, many of whom make their money from ones and zeros, the Kaufmann family’s money came from a place and its people—the matrons of Pittsburgh who needed new pantyhose, the girls who met under the store’s ornate clock, the parents who took their children to see Santa. In the age before private jets, the Kaufmanns spent their leisure time near that place too. Fallingwater was built to be their summer retreat.

Lately, though, Pennsylvania has been on the receiving end of a different display of wealth and power. Elon Musk has made Donald Trump’s return to the White House his personal cause. He has so far donated at least $119 million to his campaign group, America PAC, and has devoted considerable energy to campaigning in the state where he went to college. The South African–born Tesla magnate, who usually lives in Texas, set up what The New York Times described as a “war room” in Pittsburgh. He has held town-hall meetings in several counties across the state. He announced at a Trump event in Harrisburg that he would write $1 million checks to swing-state voters, in what the Philadelphia district attorney has described as an “illegal lottery scheme.” And Musk is presenting himself, to some skepticism, as a fan of both of the state’s NFL teams, the Philadelphia Eagles and the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Pennsylvania, which supported Democrats in six consecutive presidential elections before narrowly voting for Trump in 2016 and then returning to the Democrats in 2020, is widely expected to be the tipping-point state in the Electoral College next week. “Pennsylvania is caught in the middle of a realignment of the American electorate,” the polling analyst Josh Smithley, who runs the Pennsylvania Powered Substack, told me. The wealthier suburbs have been moving left as the rural areas “have been rocketing to the right, propelled by diminishing white working-class support for the Democratic Party.” The commonwealth is one of only six states in the country where more than 70 percent of current residents are homegrown. It is three-quarters white, and a third of its residents have a bachelor’s degree—lower than in neighboring Northeast Corridor states.

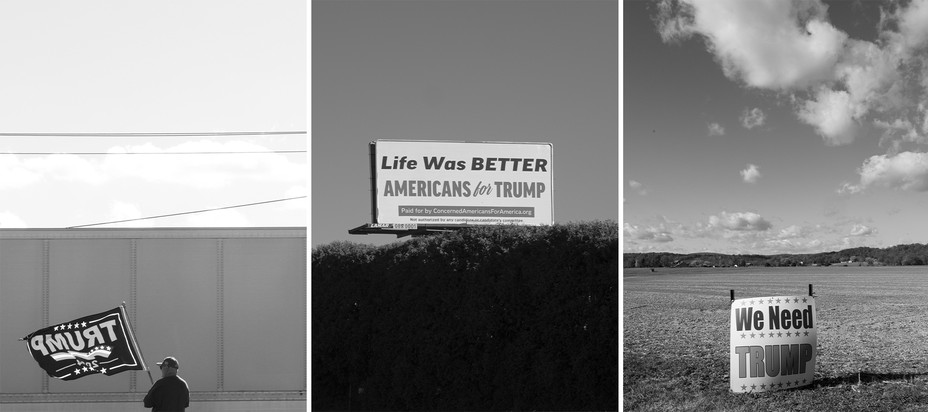

At the moment, Musk is merely the wealthiest and most frenetic of the many political operatives showering Pennsylvanians with attention. If you found yourself caught in unexpected traffic there in October, it’s quite possible that a motorcade or rally roadblock was responsible. Every television ad break is stuffed with apocalyptic messaging from the two campaigns. Leaflets are slid under doors in quantities that would make environmentalists apoplectic.

Along with the economy, Republican messaging here has focused on the border wall and crimes committed by immigrants. But Pennsylvania is also the home of one of the Democrats’ most intriguing—and most promising—pushbacks to this narrative. Folksy populists including Senator John Fetterman and vice-presidential candidate Tim Walz are peddling their own version of “beware of outsiders.” In their telling, however, the interlopers are predatory plutocrats—such as Musk—and carpetbagging candidates from out of state. During the Eagles game on October 27, a Democratic ad used a clip of Trump saying that “bad things happen in Philadelphia.” A narrator intoned, “They don’t like us. We don’t care. Because here’s the thing that people like Donald Trump don’t understand: We’re Philly. F***ing Philly.” Perhaps with a male audience in mind, the underlying visuals were ice-hockey players having a punch-up and Sylvester Stallone smacking someone in Rocky.

Both campaigns, then, are posing versions of the same question: Who are the real outsiders? Who are “they”?

In the past several months, Trump has held more than a dozen rallies and roundtables in Pennsylvania—including the one in Butler where he was nearly assassinated, and a second at the same spot, where Musk joyfully gamboled behind him before formally delivering his endorsement.

The mid-October event I attended in Reading, a small city where two-thirds of the population is Latino or Hispanic, was more low-key. But waiting to get into Santander Arena, I realized something: This was the Eras Tour for Baby Boomers. The merch. The anticipation. The rituals. The playlist of uplifting bangers. The length.

In towns and cities that feel forgotten, these rallies create a sense of community and togetherness. Taylor Swift concerts have friendship bracelets; this crowd had red Make America Great Again hats. (The “dark MAGA” version popularized by Musk was not yet en vogue.) For the Eras Tour, a concertgoer might make their own copy of Swift’s green Folklore dress, or her T-shirt that says NOT A LOT GOING ON AT THE MOMENT. The slogans at the Reading event were infinitely varied, but most were at least mildly aggressive. IF YOU DON’T LIKE TRUMP, YOU WON’T LIKE ME read one woman’s T-shirt. The men were just as fired up. For months, I have been arguing to friends that the widespread, illicit use of muscle-building steroids—which can cause rage, paranoia, and mood swings—might explain some of the political currents among American men. I usually can’t prove it, but here a large man wore a sleeveless vest that read MAKE ANABOLICS GREAT AGAIN.

Behind me in line were a mother and her two daughters—very Swiftie-coded, except they wanted to talk about “how the economy went to shit when Biden got in,” as the elder daughter put it. The mother raised the specter of Trump’s family-separation policy—which The Atlantic has extensively chronicled—only to dismiss it as a myth. She liked Trump, she told me, because he was a businessman: “People say he went bankrupt, but I think that’s smart. Finding a loophole.” Not so smart for the people he owed money to, I observed. The conversation died.

Inside the arena, I got to chatting with 34-year-old Joshua Nash, from Lititz, in Lancaster County. He was sitting alone at the back of the arena wearing a giant foam hat that he had bought on Etsy for $20 and then put in the dryer to expand. He was both a very nice guy and (to me) an impenetrable bundle of contradictions. He would be voting for Trump, he said, despite describing himself as a pro-choice libertarian who was “more left-leaning on a lot of issues.” He worked for Tesla maintaining solar panels, “but I’m not big on the whole climate thing.” He had given up on the mainstream media because of its bias and had turned to X—before Community Notes, the social-media platform’s crowdsourced fact-checking program, repelled him too. “I just want the facts,” he told me.

The campy, carnivalesque atmosphere of Trump rallies—halfway between megachurch and WrestleMania—is hard to reconcile with the darkness of the sentiments expressed within them. How could anything be alarming, many of the former president’s supporters clearly think, about such a great day out? After all, like the Eras Tour, Trump’s rally circuit has created its own lore. At the front, you might see the “Front Row Joes,” who arrive hours early to bag the best spots in the arena, or Blake Marnell, also known as “Mr. Wall,” who wears an outfit printed with bricks meant to resemble Trump’s promised border barrier. Another regular is “Uncle Sam,” who comes decked out in candy-striped trousers and a stars-and-stripes bow tie. He leads the crowd in boos and cheers.

Trump feeds off his fans’ devotion, making them part of the show. In Reading, he praised the Front Row Joes while claiming that his events were so popular, they struggled to secure front-row seats, and then moved on to “the great Uncle Sam. I got to shake his hand. I have no idea who the hell he is. I got to shake his hand two weeks ago. He has the strongest handshake. I’m saying, ‘Man, that guy’s strong.’ Thank you, Uncle Sam. You’re great. Kamala flew to a fundraiser in San Francisco, a city she absolutely destroyed.”

Did you catch that curveball there? It wasn’t any less jarring in real time. Listening to Trump’s style of speaking—which he calls the “weave”—re-creates the experience of falling asleep during a TV program and missing a crucial plot point before jerking awake and wondering why the protagonist is now in Venice. Every time I zoned out for a few seconds, I was jolted back with phrases like “We defeated ISIS in four weeks” (huh?) and “We never have an empty seat” (fact-check: I was sitting near several hundred of them), or the assertion that Howard Stern is no longer popular, so “I dropped him like a dog.” You have to follow the thread closely. Or you just allow the waves of verbiage to wash over you as you listen for trigger words like the border and too big to rig.

At his rally in Reading, Trump made several cracks about the “fake news” media, which had turned out in droves to record him from an elevated riser in the middle of the arena. “They are corrupt and they are the enemy of the people,” he said. “We give them the information and then they write the opposite, and it’s really disgusting.” A wave of booing. A man in the crowd shouted, “You suck!”

A few days later, at a rally for Vice President Kamala Harris in the windswept western city of Erie, Senator Fetterman emerged in a sweatshirt, shorts, and a yellow wool Steelers hat with a bobble that made him look like an oversize Smurf. During his short speech, Fetterman twice mentioned the media’s presence, and people actually cheered. (About a third of Democrats trust newspapers, compared with just 7 percent of Republicans, according to Gallup.) “The national media is here,” Fetterman told the audience. “Want to know why? Because you pick the president!”

Fetterman’s speech attacked a series of Republican politicians whom he depicted as outsiders—disconnected elites. He roasted the vice-presidential nominee J. D. Vance for allegedly not wanting to go to Sheetz, the convenience-store chain whose headquarters are in Altoona, Pennsylvania. He mocked his former Senate rival, the Trump-endorsed television personality Mehmet Oz, whose campaign never recovered from the revelation that he ate crudités and lived in New Jersey. He urged the crowd to vote against the Republican Senate candidate Dave McCormick, who was born in Pennsylvania but spent his hedge-fund millions on a house in the tristate area. “You’re going to send that weirdo back to Connecticut,” Fetterman told the crowd.

The signs and T-shirt slogans at the Erie rally tended to be less stern than twee. I saw a smattering of CHILDLESS CAT LADY and a lot of Brat green. During the warm-up, Team Harris entertained the crowd with a pair of DJs playing Boomer and Gen X hits: Welcome to America, where your night out can include both a sing-along to Abba’s “Dancing Queen” and a warning about the possible end of democracy. When Harris finally arrived onstage, to the sound of Beyoncé’s “Freedom,” her speech was tight, coherent … and clichéd. At one point, she asked the crowd: “Why are we not going back? Because we will move forward.” But you can’t say that Harris isn’t working for this: After the speech, she stuck around to fulfill a dozen selfie requests. At one point, I saw her literally kiss a baby.

The Democrats have placed a great deal of hope in the idea that Harris comes off as normal, compared with an opponent who rants and meanders, warning about enemies one minute and swaying along to “Ave Maria” the next (and the next, and the next …). This contrast captures what most people in the United Kingdom—where a majority of Conservative voters back Harris, never mind people on the left—don’t understand about America. How is this a close election, my fellow Britons wonder, when one candidate is incoherent and vain, the generals who know him best believe he’s a fascist, and his former vice president won’t endorse him? That message has not penetrated the MAGA media bubble, though: Time and again, I met Trump voters who thought that reelecting the former president would make America more respected abroad.

In Western Europe, many see America’s presidential election this year not as a battle between left and right, liberal and conservative, high and low taxes, but something more like a soccer game between a mid-ranking team and a herd of stampeding buffalo. Sure, the buffalo might win—but not by playing soccer.

The next day, I got up early and set my rental car’s navigation system for a destination that registered, ominously, as a green void on the screen. This was a farm outside Volant (population 126), where Tim Walz would be talking to the rare Democrats among a fiercely Trump-supporting demographic: Pennsylvania farmers.

The work ethic of farmers makes Goldman Sachs trainees look like quiet quitters, and the agricultural trade selects for no-nonsense pragmatists who are relentlessly cheerful even when they’ve been awake half the night with their arm up a cow. Accordingly, many people I met at the Volant rally didn’t define themselves as Democrats. They were just people who had identified a problem (Trump-related chaos) and a solution (voting for Harris). “I don’t think we’re radical at all,” Krissi Harp, from Neshannock Township, told me, sitting with her husband, Dan, and daughter, Aminah. “We’re just down the middle with everything … All of us voted straight blue this year, just because we have to get rid of this Trumpism to get back to normalcy.”

Danielle Bias, a 41-year-old from Ellwood City, told me she was the daughter and granddaughter of Republicans, and she had volunteered for Trump in 2016. “This will be the first time I cross the line, but this is the first time in history I feel we need to cross the line to protect our Constitution and to protect our democracy,” she said. Her husband— “a staunch Republican, a staunch gun owner”—had followed her, as well as her daughter. But not her 20-year-old son. “He believes a lot of the misinformation that is out there, unfortunately,” Bias said, such as the idea that the government controls the weather.

The Democratic plan to take Pennsylvania rests partly on nibbling away at the red vote in rural counties. The farm’s owner, Rick Telesz, is a former Trump supporter who flipped to Biden in 2020 and has since run for office as a Democrat. Telesz’s switch was brave in the middle of western Pennsylvania, Walz said in his speech, and as a result, Telesz would “probably get less than a five-finger wave” from his neighbors.

Walz is the breakout star of 2024, one of those politicians in whom you can sense the schtick—folksy midwestern dad who’s handy with a spark plug—but nevertheless get its appeal. He walked out to John Mellencamp’s “Small Town,” in which the singer expresses the hope that he will live and die in the place where he was born. Walz had dressed for the occasion in a beige baseball cap and red checked shirt, and he gave his speech surrounded by hay bales and gourds. “Dairy, pork, and turkeys—those are the three food groups in Minnesota,” he told the crowd, to indulgent laughter, in between outlining the Democrats’ plans to end “ambulance deserts,” protect rural pharmacies, and fund senior care through Medicare.

Walz also wanted to talk about place. He grew up in Minnesota, where each fall brought the opening of pheasant season, a ritual that bonded him, his father, and his late brother. “I can still remember it like it was yesterday,” he said. “Coffee brewing … The dogs are in the field. You’re on the land that’s been in your family for a long time, and you’re getting to participate in something that we all love so much—being with family, being on that land and hunting.”

Then Walz turned Trump’s most inflammatory argument around. Yes, the governor conceded, outsiders were coming into struggling communities and causing trouble. “Those outsiders have names,” he said. “They’re Donald Trump and J. D. Vance.” Why were groceries so expensive when farmers were still getting only $410 a bushel for corn and $10 for soybeans? Middlemen, Walz said—and venture capitalists like Vance. “I am proud of where I grew up,” he said. “I wouldn’t trade that for anything. And Senator Vance, he became a media darling. He wrote a book about the place he grew up, but the premise was trashing that place where he grew up rather than lifting it up. The guy’s a venture capitalist cosplaying like he’s a cowboy or something.”

On a sunny day at the Kitchen Kettle Village in Lancaster County, shoppers browsed among quilts, homemade relishes, and $25 T-shirts reading I ♥ INTERCOURSE in honor of a charming community nearby, whose sign presumably gets stolen quite often. Everyone I spoke with there was voting for Trump, and most cited the economy—specifically, inflation, which is immediately visible to voters as higher costs in stores. Among them was Ryan Santana, who was wearing a hat proclaiming him to be Ultra MAGA. He told me that money was tight—he was supporting his wife to be a stay-at-home mom to their young daughter on his salary as a plumbing technician—which he attributed to Biden’s policies. He also mentioned that he had moved from New York to Scranton to be surrounded by people who found his opinions unremarkable. “The left can do what they want,” he said. “Out in the country, we do what we want.”

Throughout my journey around Pennsylvania, I asked voters from both parties what they thought motivated the other side. Kathy Howley, 75, from Newcastle, told me at the Walz rally that her MAGA neighbors seemed to be regurgitating things they had heard on the news or online. “I try to present facts,” Howley said. “Why aren’t people listening to facts?” Many Trump voters, meanwhile, saw Democrats as spendthrifts, pouring money into their pet causes and special-interest groups, unwilling to tackle the border crisis in case they are called racist—or, more conspiratorially, because they think that migrants are future Democrats.

While out driving, I twice saw signs that read I’M VOTING FOR THE FELON. This was a mystery to me: Conservatives who in 2020 might have argued that “blue lives matter” and decried the slogan “Defund the police” as dangerous anarchy were now backing the candidate with a criminal record—and one who had fomented a riot after losing the last election. For those who planned to vote for Trump, however, January 6 was an overblown story—a protest that had gotten out of hand. “If he didn’t respect democracy, why would he run for office?” asked Johanna Williams, who served me coffee at a roadside café. When I pressed her, she conceded that Trump was no angel, but she believed he could change: “He does have a felony charge, but I still think that there is a little bit of good that he could do.” For the 20-year-old from rural Sandy Lake, stopping abortion was the biggest election issue. Even if a woman became pregnant from sexual assault, Williams believed, she should carry the pregnancy to term and give the baby to a couple who couldn’t have children.

I also met Williams’s mirror image. Rachel Prichard, a 31-year-old from Altoona, was one of those who snagged a selfie with Harris at the rally in Erie, which she proudly showed me on her phone as the arena emptied. She was voting Democratic for one reason: “women’s rights.” She had voted for Trump in 2016 “for a change,” and because she thought “he gave a voice to people who felt they didn’t have one.” Instead of helping, though, Trump had “taught them to yell the loudest.” Rachel had come to the arena with her mother, Susan, who had an even more intriguing voting history: She was a registered Republican who worried about high welfare spending and had voted for Trump twice, but she switched allegiance after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

The Prichards are part of a larger female drift toward the Democrats in this election cycle, prompted by the repeal of Roe. Many such women are unshowy and private, the type who turn out for door-knocking but would be reluctant to get up on a podium—the opposite of the male MAGA foghorns who now blight my timeline on X. If Harris outperforms the polls in Pennsylvania, and across the country, it will be in no small part because of these women.

Fallingwater might be a relic of an era when the social contract seemed stronger, but another Pennsylvania landmark reminded me that Americans have endured polarization more bitter than today’s.

In Gettysburg, the statues of Union General George Gordon Meade and Confederate General Robert E. Lee stare at each other across the battlefield for eternity— although the solemnity is somewhat disrupted by a nearby statue of Union General Alexander Hays that appears to be lifting a sword toward a KFC across the road. A stone boundary at what’s known as High Water Mark—the farthest point reached by Confederate soldiers in the 1863 battle—has become a modest symbol of reconciliation. In 1938, the last few living veterans ceremonially shook hands across the wall.

I was visiting Gettysburg to understand how the country came apart, and how its politicians and ordinary citizens tried to mend it again. The Civil War pitted American against American in a conflict that left about 2.5 percent of the population dead. During three days of fighting at Gettysburg alone, more than 50,000 soldiers were killed or wounded. The Civil War still resonates today, sometimes in peculiar ways. In Reading, Trump had asked the crowd if it wanted Fort Liberty, in North Carolina, restored to its former name of Fort Bragg, after Confederate General Braxton Bragg. His listeners roared their approval—never mind that Pennsylvania fought for the Union.

The address that Abraham Lincoln gave when he dedicated the Union cemetery there is now remembered as one of the most poignant (and succinct) in American history. By some accounts, though, it flopped at the time. “He thought it was a failure,” William B. Styple, a Civil War historian who was signing books in the visitor center’s gift shop, told me. “There was no crowd reaction.” Only when Lincoln began to read accounts of the address in newspapers was he reassured that anyone would notice his plea “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

When I reached the cemetery where Lincoln spoke, a ranger named Jerry Warren pointed me to the grass that marks historians’ best guess for the precise spot. When I told him that I was there to write about the presidential election, he paused. “In the middle of a civil war,” he said, “Lincoln never mentioned us and them.”

Now, I can’t quite believe that—the discrete categories of enemies and allies are sharply defined during wartime, as the blue and gray military caps in the gift shop made clear. But I see why Pennsylvanians might reject the suggestion that the gap between red and blue is unbridgeable. What I heard from many interviewees across the political spectrum was a more amorphous sense that something has gone amiss in the places they hold dear, and that nobody is stepping in to help. Perhaps a fairer way to see things is that many communities in Pennsylvania feel overlooked and underappreciated three years out of every four—and the role of a political party should be to identify the source of that malaise.

When I came back to Pittsburgh from Fallingwater, I got to talking with Bill Schwartz, a 55-year-old lifelong city resident who works the front desk at the Mansions on Fifth Hotel—another legacy of the city’s industrial golden age, built for the lawyer Willis McCook in 1905. Within a minute, he began to tell me about the diners and dime stores of his youth, now gone or replaced with vape shops and empty lots. (The Kaufmann family’s once-celebrated department store rebranded after Macy’s bought the chain in 2005. Its flagship location later closed.)

Schwartz, who is Black, lowered his voice as he recounted the racial slurs and insults that were shouted at him in the 1980s. But he fondly remembered the Gus Miller newsstand, dinners at Fat Angelo’s downtown, and nights at Essie’s Original Hot Dog Shop in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood, home of a gnarly stalagmite of carbs known as “O Fries.” “It was a great hangout spot,” he said—his version of the bar in Cheers. But after the pandemic, he wandered down there and discovered a load of guys in construction gear. They had already gutted the place down to its wooden beams.

Did anyone try to save the Original Hot Dog Shop? Schwartz sighed. “That would require rich people to care about where they came from.”