The Lessons of 1800

6 min read

Americans are headed to the polls today, to cast their ballots in a crucial election. People are anxious, hopeful, and scared about the stakes of the election and its aftermath. But this is not the only such electoral test that American democracy has faced. An earlier contest has much to say to the present.

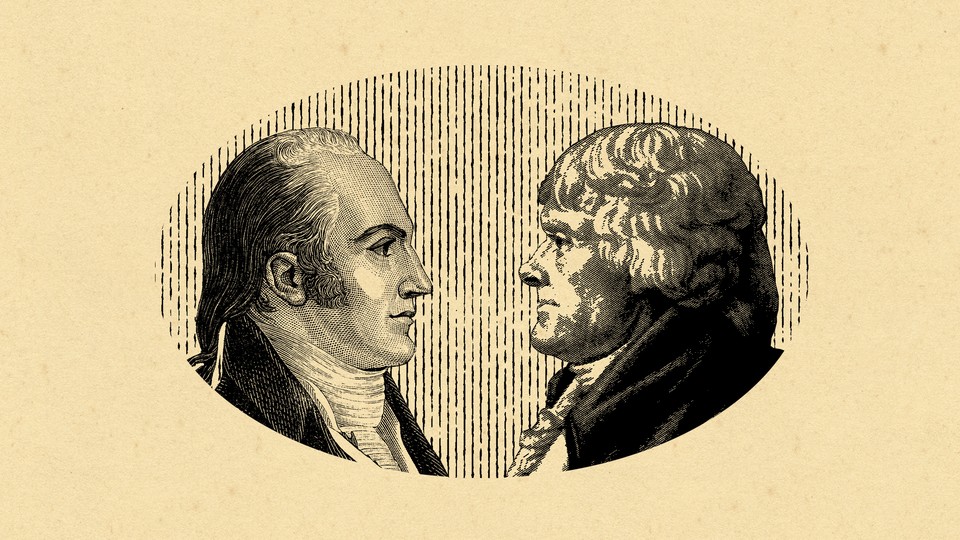

The presidential election of 1800 was a crisis of the first order, featuring extreme polarization, wild accusations, and name-calling—the Federalist John Adams was labeled “hermaphroditical” by Republicans, and Federalists, in turn, warned that Thomas Jefferson would destroy Christianity. People in two states began stockpiling arms to take the government for Jefferson if necessary, seeing him as the intended winner. Federalist members of Congress considered overturning the election; thousands of people surrounded the Capitol to learn the outcome; and an extended, agonizing tie between Jefferson and Aaron Burr took 36 votes to resolve in the House of Representatives.

We’re not looking at a replay of the 1800 election; history doesn’t repeat itself. But two key components of that electoral firestorm are speaking loudly to the present: the threat of violence, and the proposed solution to the electoral turmoil after the contest’s close.

The unfortunate truth is that democratic governance is often violent. When the promises and reach of democracy expand, it almost always brings an antidemocratic blowback, sometimes including threats and violence. Black men gaining the right to vote during the Civil War was met with bluntly hostile threats, intimidation, and voter suppression during Reconstruction. The advancing demands for the civil rights of Black Americans in the 1960s led to vicious beatings and murders. In both eras, white Americans who felt entitled to power—and who felt threatened by the expanding rights and opportunities granted to racial minorities through democratic means—resorted to violence.

At the end of the 18th century, the Federalists were the party of extreme entitlement. They favored a strong central government with the power to enforce its precepts and were none too comfortable with a democratic politics of resistance, protest, and pushback. They wanted Americans to vote for their preferred candidates, then step aside and let their betters govern.

When Jefferson and Burr—both Democratic Republicans—received an equal number of electoral votes, the Federalists were horrified. They faced the nightmare choice between Jefferson, a notoriously anti Federalist Republican, or Burr, an unpredictable and opportunistic politico with unknown loyalties. They largely preferred Burr, who seemed far more likely to compromise with the Federalists.

Tied elections are thrown to the House of Representatives to decide, with each state getting one vote. Given this chance to steal the election, Federalists inside and outside Congress began plotting—perhaps they could prevent the election of either candidate and elect a president pro tem until they devised a better solution.

Federalist talk of intervention didn’t go unnoticed. Governors in Pennsylvania and Virginia began to stockpile arms in case the government needed to be taken for Jefferson. This was no subversive effort; Jefferson himself knew of their efforts, telling James Madison and James Monroe that the threat of resistance “by arms” was giving the Federalists pause. “We thought it best to declare openly & firmly, one & all, that the day such an act [of usurpation] passed the middle states would arm.”

Ultimately, there was no violence. But the threat was very real—a product of the fact that Federalists felt so entitled to political power that they were unwilling to lose by democratic means. And losing is a key component of democracy. Elections are contests with winners and losers. Democracy relies on these free and fair contests to assign power according to the preferences of the American people. People who feel entitled to power are hostile to these contests. They won’t accept unknown outcomes. They want inevitability, invulnerability, and immunity, so they strike out at structures of democracy. They scorn electoral proceedings, manipulate the political process, and threaten their opponents. Sometimes, the end result is violence. In the election of 2024, this is the posture adopted by former President Donald Trump and his supporters. As in 1800, a steadfast sense of entitlement to power is threatening our democratic process.

The election of 1800 was just the fourth presidential contest in American history, and only the election of 1796, the first without George Washington as a candidate, had been contested. After the crisis of 1800, some people sought better options. Unsettled by the uproar of 1800, at least one Federalist favored ending popular presidential elections altogether. Thinking back to the election a few years later, the Connecticut Federalist James Hillhouse proposed amending the constitutional mode of electing presidents. The president should be chosen from among acting senators, he suggested. A box could be filled with balls—most of them white, one of them colored— and each senator who was qualified for the presidency would proceed in alphabetical order and pull a ball from the box. The senator who drew the colored ball would be president. Chief Justice John Marshall, who agreed that presidential contests were dangerous, declared the plan as good as any other.

Most people didn’t go that far, but Federalists and Republicans alike understood that the threat posed by fiercely contested partisan elections could be dire. Although the presidency had been peacefully transferred from one party to another, the road to that transfer had been rocky. Stockpiling arms? Threats of armed resistance? Seizing the presidency? The entire nation rocked by political passions, seemingly torn in two?

One Republican asked Jefferson in March 1801: What would have happened if there had been the “non election of a president”? Jefferson’s response is noteworthy. In that case, he wrote, “the federal government would have been in the situation of a clock or watch run down … A convention, invited by the republican members of Congress … would have been on the ground in 8 weeks, would have repaired the constitution where it was defective, and wound it up again.”

The political process would save the nation. A convention. Perhaps amending the Constitution. The solution to the crisis, Jefferson argued, lay in tried-and-true constitutional processes of government. As he put it, they were a “peaceable & legitimate resource, to which we are in the habit of implicit obedience.”

And indeed, that is the purpose of the Constitution, a road map of political processes. As Americans, we agree to abide by its standards or use constitutional and legal political means to change them. When people attack the Constitution—threaten it, ignore it, violate it—they are striking a blow to the constitutional pact that holds us together as a nation. We don’t often think about this pact, or even realize that it’s there—until it’s challenged.

Which brings us to the present. Today’s election presents a stark choice. Americans can either respect the basic constitutional structures of our government, or trample them with denial and lies. The Constitution is far from perfect. It needs amending. But it is our procedural starting point for change.

By voting, you are signaling your belief in this process. You are declaring that you believe in the opportunities presented by democracy, even if they sometimes must be fought for. Democracy isn’t an end point; it’s a process. This election is our opportunity to pledge our allegiance to that process—to the constitutional pact that anchors our nation. The choice is ours.