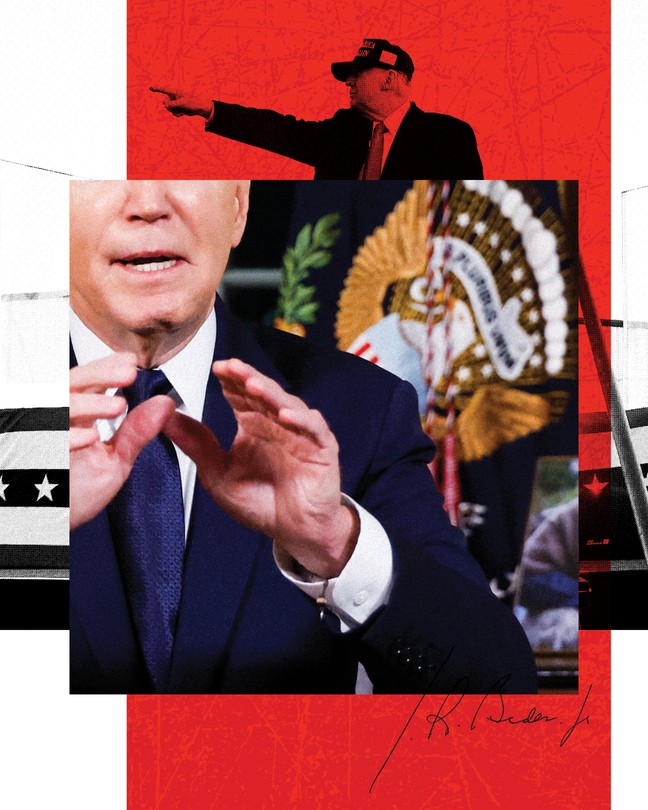

Pardon Trump’s Critics Now

5 min read

Over the past several years, courageous Americans have risked their careers and perhaps even their liberty in an effort to stop Donald Trump’s return to power. Our collective failure to avoid that result now gives Trump an opportunity to exact revenge on them. President Joe Biden, in the remaining two months of his term in office, can and must prevent this by using one of the most powerful tools available to the president: the pardon power.

The risk of retribution is very real. One hallmark of Trump’s recently completed campaign was his regular calls for vengeance against his enemies. Over the past few months, he has said, for example, that Liz Cheney was a traitor. He’s also said that she is a “war hawk.” “Let’s put her with a rifle standing there with nine barrels shooting at her,” he said. Likewise, Trump has floated the idea of executing General Mark Milley, calling him treasonous. Meanwhile, Trump has identified his political opponents and the press as “enemies of the people” and has threatened his perceived enemies with prosecution or punishment more than 100 times. There can be little doubt that Trump has an enemies list, and the people on it are in danger—most likely legal, though I shudder to think of other possibilities.

Biden has the unfettered power to issue pardons, and he should use it liberally. He should offer pardons, in addition to Cheney and Milley, to all of Trump’s most prominent opponents: Republican critics, such as Adam Kinzinger, who put country before party to tell the truth about January 6; their Democratic colleagues from the House special committee; military leaders such as Jim Mattis, H. R. McMaster, and William McRaven; witnesses to Trump’s conduct who worked for him and have since condemned him, including Miles Taylor, Olivia Troye, Alyssa Farah Griffin, Cassidy Hutchinson, and Sarah Matthews; political opponents such as Nancy Pelosi and Adam Schiff; and others who have been vocal in their negative views, such as George Conway and Bill Kristol.

The power to pardon is grounded in Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, which gives a nearly unlimited power to the president. It says the president “shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” That’s it. A president’s authority to pardon is pretty much without limitation as to reason, subject, scope, or timing.

Historically, for example, Gerald Ford gave Richard Nixon a “full, free, and absolute pardon” for any offense that he “has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 20, 1969 through August 9, 1974.” If Biden were willing, he could issue a set of pardons similar in scope and form to Trump’s critics, and they would be enforced by the courts as a protection against retaliation.

There are, naturally, reasons to be skeptical of this approach. First, one might argue that pardons are unnecessary. After all, the argument would go, none of the people whom Trump might target have actually done anything wrong. They are innocent of anything except opposing Trump, and the judicial system will protect them.

This argument is almost certainly correct; the likelihood of a jury convicting Liz Cheney of a criminal offense is laughably close to zero. But a verdict of innocence does not negate the harm that can be done. In a narrow, personal sense, Cheney would be exonerated. But along the way she would no doubt suffer—the reputational harm of indictment, the financial harm of having to defend herself, and the psychic harm of having to bear the pressure of an investigation and charges.

In the criminal-justice system, prosecutors and investigators have a cynical but accurate way of describing this: “You can beat the rap, but you can’t beat the ride.” By this they mean that even the costs of ultimate victory tend to be very high. Biden owes it to Trump’s most prominent critics to save them from that burden.

More abstractly, the inevitable societal impact of politicized prosecutions will be to deter criticism. Not everyone has the strength of will to forge ahead in the face of potential criminal charges, and Trump’s threats have the implicit purpose of silencing his opposition. Preventing these prosecutions would blunt those threats. The benefit is real, but limited—a retrospective pardon cannot, after all, protect future dissent, but as a symbol it may still have significant value.

A second reason for skepticism involves whether a federal pardon is enough protection. Even a pardon cannot prevent state-based investigations. Nothing is going to stop Trump from pressuring his state-level supporters, such as Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, to use their offices for his revenge. And they, quite surely, will be accommodating.

But finding state charges will be much more difficult, if only because most of the putative defendants may never have visited a particular state. More important, even if there is some doubt about the efficaciousness of federal pardons, that is no reason to eschew the step. Make Trump’s abuse of power more difficult in every way you can.

The third and final objection is, to my mind at least, the most substantial and meritorious—that a president pardoning his political allies is illegitimate and a transgression of American political norms.

Although that is, formally, an accurate description of what Biden would be doing, to me any potential Biden pardons are distinct from what has come before. When Trump pardoned his own political allies, such as Steve Bannon, the move was widely (and rightly) regarded as a significant divergence from the rule of law, because it protected them from criminal prosecutions that involved genuine underlying criminality. By contrast, a Biden pardon would short-circuit bad-faith efforts by Trump to punish his opponents with frivolous claims of wrongdoing.

Still, pardons from Biden would be another step down the unfortunate road of politicizing the rule of law. It is reasonable to argue that Democrats should forgo that step, that one cannot defend norms of behavior by breaking norms of behavior.

Perhaps that once was true, but no longer. For the past eight years, while Democrats have held their fire and acted responsibly, Trump has destroyed almost every vestige of behavioral limits on his exercises of power. It has become painfully self-evident that Democratic self-restraint is a form of unilateral disarmament that neither persuades Trump to refrain from bad behavior nor wins points among the undecided. It is time—well past time—for responsible Democrats to use every tool in their tool kit.

What cannot be debated is that Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris owe a debt not just of gratitude but of loyalty to those who are now in Trump’s investigative sights. They have a moral and ethical obligation to do what they can to protect those who have taken a great risk trying to stop Trump. If that means a further diminution of legal norms, that is unfortunate, but it is not Biden’s fault; the cause is Trump’s odious plans and those who support them.