In Search of a Faith Beyond Religion

8 min read

My immigrant parents—my father especially—are ardent Christians. As such, my childhood seemed to differ dramatically from the glimpses of American life I witnessed at school or on television. My parents often spoke of their regimented, cloistered upbringings in Nigeria, and their belief that Americans are too lax. They devised a series of schemes to keep us on the straight and narrow: At home, we listened to an unending stream of gospel music and watched Christian programming on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. The centerpiece of their strategy, however, was daily visits to our small Nigerian church, in North Texas.

I quickly discerned a gap between the fist-pumping, patriotic Christianity that I saw on TV and the earnest, yearning faith that I experienced in church. On TV, it seemed that Christianity was not only a means of achieving spiritual salvation but also a tool for convincing the world of America’s preeminence. Africa was mentioned frequently on TBN, but almost exclusively as a destination for white American missionaries. On-screen, they would appear dour and sweaty as they distributed food, clothes, and Bibles to hordes of seemingly bewildered yet appreciative Black people. The ministers spoke of how God’s love—and, of course, the support of the audience—made such donations possible, but the subtext was much louder: God had blessed America, and now America was blessing everyone else.

In church, however, I encountered an entirely different type of Christianity. The biblical characters were the same, yet they were evoked for different purposes. God was on our side because we, as immigrants and their children, were the underdogs; our ancestors had suffered a series of losses at the hands of Americans and Europeans, just as the Israelites in the Bible had suffered in their own time. And like those chosen people, we would emerge victorious.

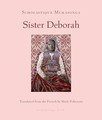

Over time, I learned that Christianity is a malleable faith; both the powerful and the powerless can use it to justify their beliefs and actions. This is, in part, the message of Scholastique Mukasonga’s Sister Deborah, which was published in France in 2022 and was recently released in the United States, in a translation by Mark Polizzotti. Set in Rwanda in the 1930s, the novel spotlights a group of recently arrived African American missionaries who preach a traditional Christian message about a forthcoming apocalypse, but with a twist: They prophesize that “when everything was again nice and dry, Jesus would appear on his cloud in the sky and everyone would discover that Jesus is black.” These missionaries are a destabilizing influence in a territory dominated by another version of Christianity, established and spread by the colonizing Belgians, that emphasizes the supremacy of a white Jesus.

The most vital force in the novel is Sister Deborah herself. She is the prophetic, ungovernable luminary of the African American contingent, and possesses healing powers. Over the course of her time in Rwanda, she develops a theology that centers Black women; as a result, she is eventually castigated by her former mentor, Reverend Marcus, a gifted itinerant preacher who serves as the leader of the missionaries. Sister Deborah is a novel about the capaciousness of Christianity but also the limits of its inclusivity—particularly for the women in its ranks.

Those limits are evident throughout the novel. The first section is narrated by a woman, Ikirezi, who recalls her childhood in Rwanda. She’d been a “sickly girl” who required constant attention, yet her mother had avoided the local clinic: She had “no confidence in the pills that the orderlies dispensed, seemingly at whim.” Ikirezi’s mother eventually determines that her child’s chronic illness comes “from either people or spirits.” So, in a fit of desperation, she decides to take her to Sister Deborah. She doesn’t know much about this American missionary except that she is a “prophetess” who possesses the gift of “healing by laying on hands.” Upon learning of his wife’s plans, Ikirezi’s father explodes:

You are not going to that devil’s mission. I forbid it! Didn’t you hear what our real padri said about it? They’re sorcerers from a country called America, a country that might not even exist because it’s the land of the dead, the land of the damned. They have not been baptized with good holy water. And they are black—all the real padri are white. I forbid you to drag my daughter there and offer her to the demon hiding in the head and belly of that witch you call Deborah. You can go to the devil if you like, but spare my daughter!

Through Ikirezi’s father’s outburst, Mukasonga deftly sketches the two opposing Christian camps in the novel—one that depends on the Bible to protect its status, and the other that uses the Bible to attain status. The white padri (priests) seek to maintain their spiritual control of the local population by labeling the African American missionaries as evil interlopers. The missionaries, for their part, have positioned themselves as an alternative religious authority, and they begin to attract many followers, especially women, who are drawn to their energetic services and Sister Deborah’s supernatural abilities.

Ikirezi’s mother defies her husband and takes Ikirezi to see Sister Deborah. They arrive at the American dispensary, where Sister Deborah holds court “under the large tree with its dazzling red flowers, sitting atop the high termite mound that had been covered by a rug decorated with stars and red stripes.” She asks the children who are gathered before her, Ikirezi among them, “to touch her cane while she lay her hands on their heads.” Afterward, Ikirezi recalls “that under the palms of her hands, a great sense of ease and well-being spread through me.” Ikirezi’s depiction of Sister Deborah remains more or less at this pitch through the rest of this section: deferential and mystified, studied but also somewhat distant. As time passes, Ikirezi’s reverence for Sister Deborah only grows, forming a scrim that obscures the healer in a hazy glow.

The novel then pivots to Sister Deborah’s point of view; she expands on and revises Ikirezi’s portrait of her life. As a child in Mississippi, Sister Deborah discovered that she had healing powers. Her mother pulled her out of school, dreading “people’s vindictiveness as much as their gratitude” for her daughter’s gift. Shortly afterward, Sister Deborah is raped by a truck driver, which shifts the trajectory of her life dramatically. She has a profound religious experience when she visits a local church, and soon after falls in with Reverend Marcus.

Reverend Marcus initially sees Sister Deborah as a tool to advance his own ambitions. He is concerned about the suffering of Black people around the world: “the contempt, insults, and lynchings they endured in America; the enslavement, massacres, and colonial tyranny forced upon them in Africa.” His theology is focused not only on their salvation but on their ascendancy as well.

Sister Deborah begins to perform healings during Reverend Marcus’s revival services, and eventually, he brings her along on a missionary trip to Rwanda. There, the reverend and Sister Deborah initially work in harmony, attracting devoted new converts. But their partnership begins to fray when a divine spirit informs Sister Deborah that a Black woman, not a Black Jesus, will save them. Reverend Marcus’s response is both a warning and a prophecy: “If we follow you in your visions and dreams, we step outside of Christianity and venture into the unknown.”

Although the reverend initially accepts Sister Deborah’s “vision” of female power, he eventually uses it to undermine her, condemning her as a witch. Even within his progressive and radical theology, Reverend Marcus believes that women must serve men; in Mukasonga’s telling, he is a man whose shortsightedness and thirst for power eventually overwhelm his generally good intentions. His behavior reflects a reality that many Christian women have experienced, Black women in particular. In Rwanda, Sister Deborah is contending with a caste system that installed white men at the top and placed Black women at the bottom. Sister Deborah’s claim that the savior is a Black woman undermines that status quo. And the reverend’s response reveals a contradiction that many Black Christian women have faced: They are encouraged to seek spiritual freedom but are still expected to remain subservient.

What Reverend Marcus doesn’t realize, however, is that his warning about “ventur[ing] into the unknown” has also given Sister Deborah a route for her own liberation. Like the women in Mukasonga’s prior work—a collection of accomplished memoirs, novels, and short fiction—Sister Deborah explores and then occupies unfamiliar realms. Unfamiliar, that is, to men, who create hierarchies in which they can flourish and then mark any territory beyond their reach as benighted. Yet it is in those benighted spaces, Sister Deborah comes to believe, that Black women can thrive. A group of women begins to follow her, and she changes her name to Mama Nganga. Little girls collect “healing plants” for her. She treats local sex workers, and invites homeless women to stay with her. She constructs an ecosystem of care and protection for women and proudly claims the label that Ikirezi’s father placed on her at the beginning of the novel: “I’m what they call a witch doctor, a healer, though some might say a sorceress,” she declares. “I treat women and children.” For Sister Deborah, Reverend Marcus’s Christianity is inadequate because it prioritizes dominance over service. She abandons that approach in favor of pursuing the true mission of Jesus: to uplift and care for the most vulnerable.

Mukasonga’s slim novel is laden with ideas, but perhaps the most potent and urgent is her assertion that sometimes, Black women cannot achieve true freedom within the confines of Christianity. By exposing how even progressive interpretations of the faith can uphold patriarchal norms, Mukasonga invites her reader to question the limitations imposed on marginalized believers. In Sister Deborah, real liberation lies in eschewing conformity to any dogma, even the Bible. But the novel is more than a critique of religious institutions: It is a call to redefine faith, perhaps even radically, on one’s own terms.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.