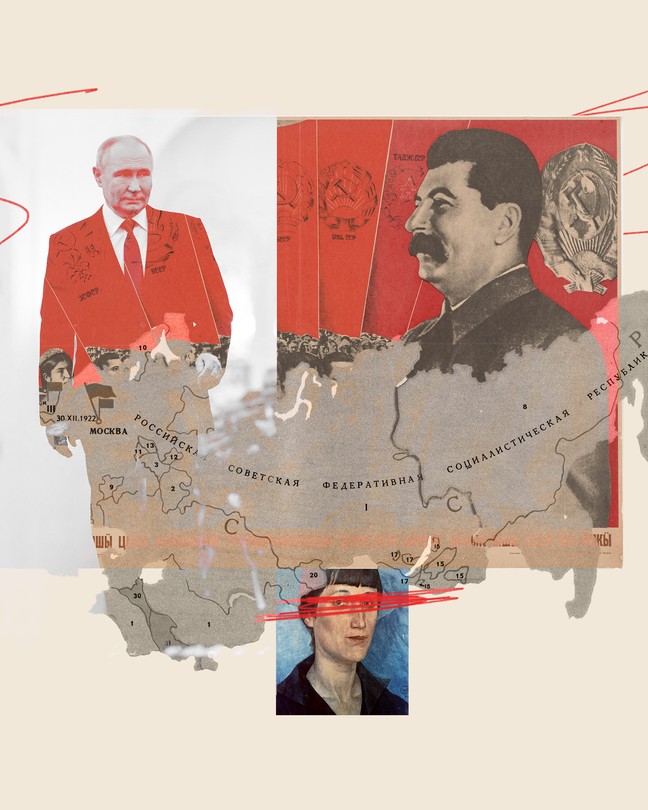

Putin Is Making Stalin’s Victims Guilty Again

6 min read

Recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government announced the “rescission” of a 1991 law officially rehabilitating past victims of political tyranny. Beginning in the late ’80s, an efflorescence of truth under the leaders Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin had revealed the full extent of the Soviet Union’s horrific crimes against its own citizens. Ultimately, more than 3.5 million defendants—people whom that now-extinct totalitarian regime had arrested, tortured, sentenced to monstrous terms in the Gulag, or shot to death—were acquitted, in many cases posthumously.

The new move to reinstate charges is ostensibly aimed at “traitors of the Motherland and Nazi accomplices” during World War II, or the Great Patriotic War as it’s known in Russia. But the enormous scope of the operation will almost certainly include other victims of Soviet “justice” during the reign of the dictator Joseph Stalin. Putin’s prosecutor general is moving quickly, having already reinstated the charges against 4,000 people as part of a two-year “audit.”

The cases against these defendants will be reviewed under articles of the Criminal Code that can be construed expansively. One punishes “state treason”; another, “secret cooperation” with the state’s enemies. The latter article was adopted only in 2022. Which means that some long-dead people who until now were deemed to have been wrongly convicted will be re-prosecuted under a law that did not exist when their alleged crimes were committed.

To most people outside Putin’s Russia, the resentencing of deceased political prisoners will appear ludicrous. Why go to all this trouble? In fact, these cases reveal something important about how his regime operates. From 2000 to about 2010, rapid economic growth was the key source of Putin’s popularity and his regime’s legitimacy. But that phase petered out. Since then, Putin has sought instead to rally the public to the defense of a motherland besieged by the perfidious and cunning West. Hoping to present an appealing vision of the future, he has declared his Kremlin an heir to an idealized version of the Soviet Union—a mighty and benign superpower, the bane of Nazis, a moral and military counterweight to America. Putin, a former KGB agent, believes that the Soviet era was glorious and wants his subjects to feel inspired by it. And if that means relitigating decades-old cases to justify Stalin’s terror against his own people, Putin is happy to do it.

The process of de-rehabilitation is deliberately murky. According to the British Broadcasting Corporation, the names of defendants and almost all case records are classified. The courts accept the legitimacy of Stalinist judicial institutions—including “special departments,” military tribunals, and the infamous “troikas” of officials who efficiently sentenced prisoners to exile or death—and original sentences are confirmed without any new corroborating evidence.

Foremost among the likely targets are the alleged Ukrainian “Nazis”—that is, nationalists who resisted Soviet reoccupation after World War II. The overthrow of their alleged “heirs” in the current “neo-Nazi Kiev regime” was one of Putin’s stated reasons for invading Ukraine.

Indeed, the Kremlin’s systematic assault on historical memory is tightly bound up with the war on Ukraine. In order to keep sending Russians to die or be maimed in combat, Putin urgently needs them to accept—and even feel moved by—the idea that Russia’s bright future lies in the Soviet past and that they are fighting to recover the Soviet Union’s unchallenged might.

Putin has long sensed what pro-democracy revolutionaries of the late 1980s and early 1990s tended to disregard: many Russians’ deep-seated trauma from the loss of their country’s exalted place in the world. Asked in a 2011 national survey whether “Russia must restore its status of a great empire,” 78 percent of Russians agreed. Instead of continuing to reckon, as Gorbachev and Yeltsin did, with the true causes of the Soviet Union’s fall from superpower status, Putin would rather erase the public’s memory of the millions arrested and tortured, shot after five-minute “trials,” exiled to sicken and die, or worked and starved to death in the Gulag.

In 2015, a Gulag museum in the Perm region was “redesigned” to de-emphasize political prisoners. It was part of a pattern that continues to this day. Four years ago, while amending the Russian constitution to effectively make himself president for life, Putin inserted an article committing the government to the “the defense of historical truth.” In reality, the measure gave him even more power to suppress and rewrite history. In 2022, four days after Russia invaded Ukraine, the authorities shut down the group International Memorial, which had been founded in the late ’80s by the former dissident Andrei Sakharov and others to monitor political imprisonment and preserve memories of Stalinist terror.

The war accelerated what the Russian newspaper Kommersant called an “epidemic of destruction of the memorials to the victims of Stalinist repression.” At least 22 monuments disappeared between February 2022 and November 2023. In St. Petersburg, a memorial board with lines from Anna Akhmatova’s world-renowned poem Requiem was removed from the wall of a former prison where the great Russian poet recalled standing “for 300 hours” waiting for news of her arrested son. Last month, Moscow authorities shut down the authoritative and artistically stunning Museum of Gulag History over an alleged violation of fire-safety regulations.

Meanwhile, monuments to Stalin’s Soviet Union are proliferating. This summer, Kommersant counted 110 obelisks and statues commemorating Stalin himself. Almost half had been erected in the past 10 years. The sculptures are said to be “privately funded,” usually by local Communists. But they would not be tolerated in public space without the Kremlin’s permission.

The most influential of Stalin memorials is being raised in the minds of the young. From birth, the “Putin generation” has known no other leader. The 635,000 students—and potential future soldiers—who graduated from high school this year learned Soviet history from an 11th-grade textbook that the prominent dissident Dmitri Savvin described as the “most Stalinophilic item” in Russian territory since Stalin’s death in 1953. In the textbook’s narrative, the butcher of millions is never culpable. His monstrous deeds are either omitted, explained away, or copied uncritically from official Soviet narratives.

For example, his Great Purge of 1936–38, a bacchanal of death, is merely the result of a “complicated international situation” and the threat of a new world war. In “such circumstances,” the textbook instructs, Stalin “thought it necessary” to suppress “domestic opposition”—people who in the case of an invasion might have become a “fifth column,” stabbing the Soviet Union in the back. Anyway, the textbook avers, the repressions seemed justified to most Soviet citizens, and Stalin’s popularity “not only did not diminish” but “continued to grow.” Undiscussed is how, after the Nazi invasion began in 1941, Stalin hid out in his dacha for 10 days before addressing the public, or how the execution of virtually all senior military commanders in the Great Purge contributed to the military disasters that soon followed.

After Stalin’s death, the Soviet government admitted that many of his victims had been wrongly accused. Others were officially rehabilitated beginning in the final years of the Soviet Union, when a consensus emerged that if Russia failed to face the truth about Stalin and his regime, a democratic future would be subverted. Only a perpetual, living, and constantly renewed memory of the mass murder would prevent the restoration of a criminal, authoritarian regime.

Putin too understands this. That is why his government is methodically reviving criminal charges against thousands of previously exonerated victims of the Soviet regime. “Who controls the past, controls the future,” George Orwell wrote in 1984. “Who controls the present, controls the past.” Putin’s historical revisionism has become an indispensable feature of his regime. And as long as he controls the present, his war on memory will only broaden and deepen.