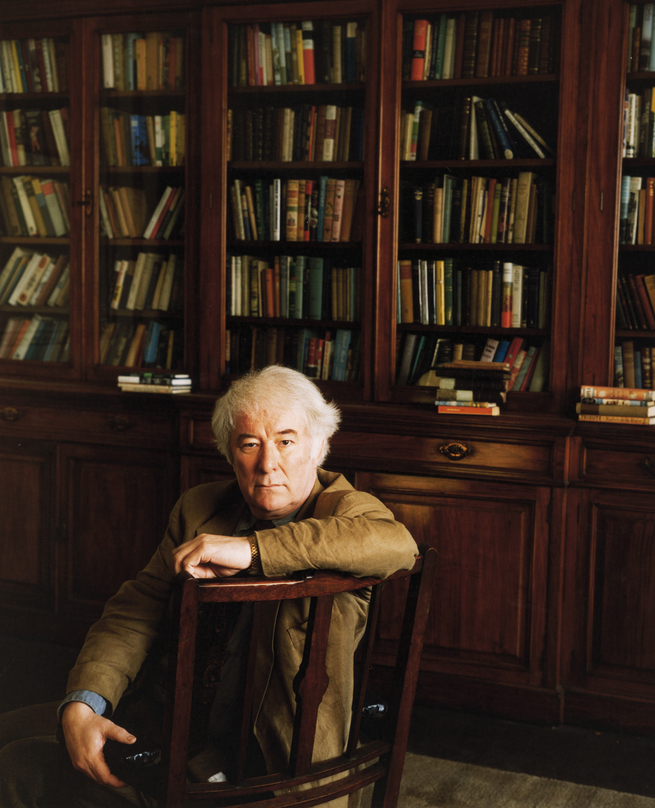

What Seamus Heaney Gave Me

26 min read

When my older sister, Ellen, was 4 or 5, she and a neighbor girl were playing in the front yard of our Berkeley house. The friend, who lived across the street, was the daughter of a Lutheran minister, who our father thought was a pompous and ridiculous person. Suddenly, Ellen slammed through the kitchen door and pounded upstairs to our father’s study.

“Daddy, Daddy!” she cried out in anguish. “Margaret Mumm says there’s no Santa Claus!”

Our father stopped typing, considered briefly what she’d told him, and then said, “You tell Margaret Mumm there’s no God.”

In the Berkeley Hills, long, public staircases run between streets like steep sidewalks, and the minister and his family lived in a house built next to one of them. So, not long after Ellen ran off, as my father looked through the window above his desk, he saw the man approach like an advancing filmstrip: first the shiny black shoes, then the black pant legs, and soon enough the whole of him, making his way to the bottom step and crossing the street.

In America in the ’60s, members of the clergy were generally considered moral authorities and accorded a certain measure of respect. But this particular clergyman was placing a very bad bet if he thought he could pay a visit to Tom Flanagan and tell him the right way to talk to his children about God.

After the inevitable knock at the door, my father descended the stairs, and then there it was: American Mainline Protestantism face-to-face with post-Hiroshima rational thought. The minister must have assumed that Tom would at the very least invite him in, but he didn’t, so the man was forced to stand on the front porch and reduce his plaint to its elements.

“Your daughter told my daughter that there is no God,” he said, more in sorrow than in anger. I think it was meant to be a pastoral visit.

“And your daughter told my daughter that there is no Santa Claus,” my father replied.

“But—there is no Santa Claus!” the minister sputtered.

“And there is no God.”

We didn’t have any notion of God in our house, but we certainly had Christmas, and with it revealed truth: the carrots on the front porch, eaten down to stumps! The presents piled under the tree, with our names on them! Our cosmology was just as considered as his.

Until all of this certainty was challenged.

Ten years later, Ellen and I were called down to the living room of a rented house in Dublin, where we were spending one of our father’s endless sabbatical years (I went to first, fifth, and tenth grade in Ireland), and tersely informed that we were going to be baptized.

We shrieked in horror. If our parents had told us they were getting divorced, we would have taken the news with equanimity. We would have said, “Hey, you gave it your best shot,” and recommended that they wait until we got back to California, where theocracy would not impede their plans. But religion? There was no explanation for it; they certainly didn’t say they’d had their own conversions.

Ellen spoke for us both: “I’m not doing it!”

I echoed her: “No way!”

Our parents were up to something, and clearly our mother, Jean, was the instigator. Tom would much later confess that the whole thing was a hypocritical plan that my mother had hatched to get us into Catholic schools (which were like private schools, but cheap) when we returned to Berkeley.

Jean was unmoved by our yelps of disgust and fear. We were to be whipped through the tenets of the faith via weekly lessons delivered at a convent school by two nuns (one for Ellen, and one for me), and the event would occur early one evening in December, in time for a drinks party afterward. The guests would be 25 of my parents’ friends. Would we like to invite any of our own friends? We would rather be buried alive.

The first lesson was the next day, and I began my session with tea in a cup and saucer—very civilized—and biscuits. But no sooner had I eaten the last Jaffa Cake on the plate than we turned to Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride: the virgin birth (“What’s a virgin?” “It’s a girl who hasn’t even met a boy”); the Crucifixion (holy shit!); original sin; confession; the Eucharist; priests’ ability to transform ordinary bread and wine into literal (this was very, very important to understand: not symbolic—literal) human blood and flesh, a tiny bit of which we would be consuming once a week for the rest of our lives.

You can’t jump people into Roman Catholicism after the age of reason; they have to “come to God” on their own, or be in some kind of trouble. We didn’t believe any of it, and not just because of what our parents had always told us. It didn’t sound plausible. We lay in our beds at night and fumed. At the baptism, Ellen and I would have to have water poured on our long hair, like a couple of idiots. We would have to say something about believing in God, and we would have to reject the devil and all his pomps. (Pomps : shows of magnificence, splendor. Enough said! Rejected!) We took our final lesson, and a rehearsal was staged. Someone made a fruitcake with marzipan icing. In Ireland, when a woman makes a fruitcake, there’s no turning back. We were fucked.

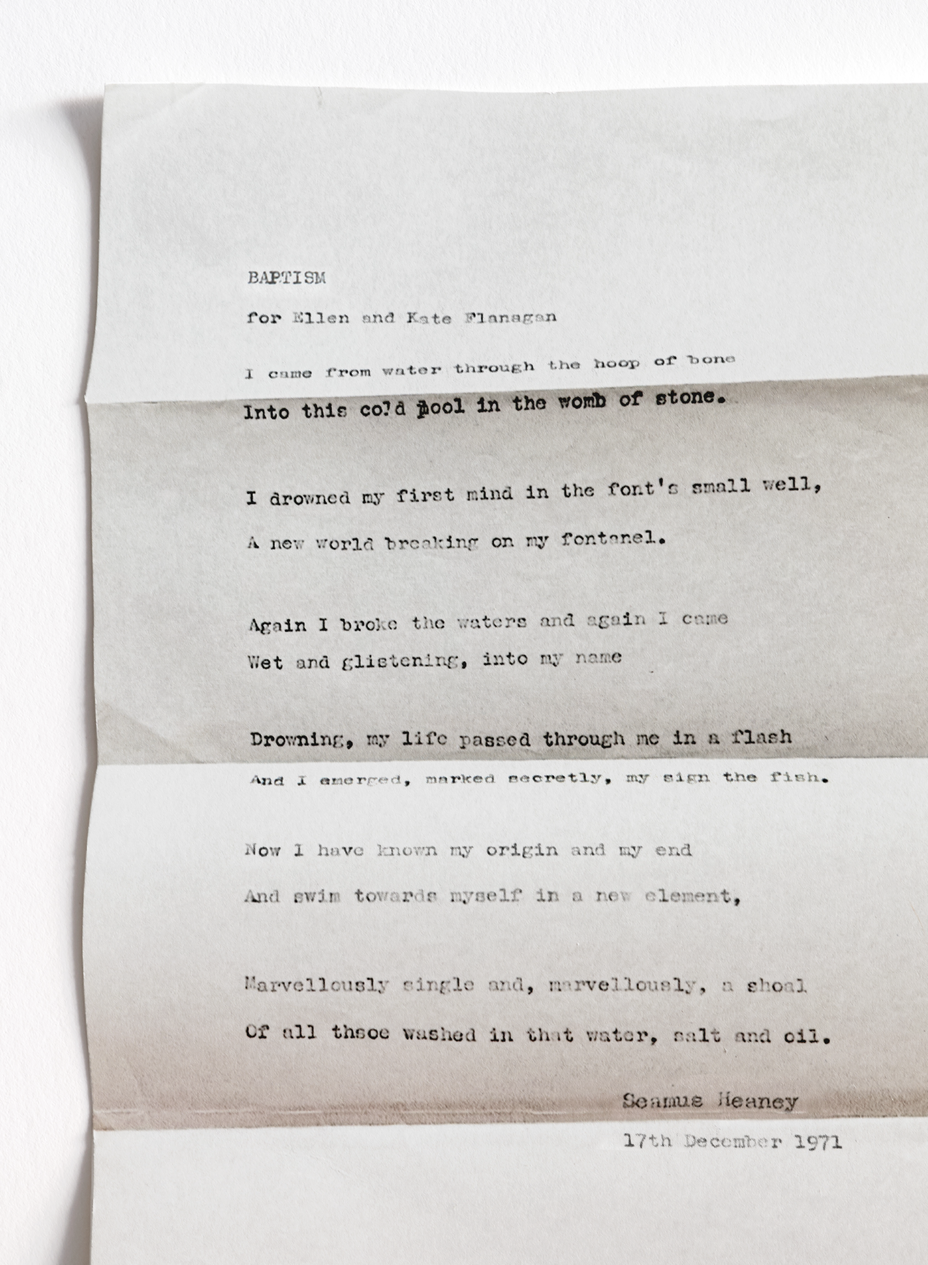

But then—like a dream, like a magic fish bone—word arrived from Belfast that Seamus and Marie Heaney were coming down for the event, and that Seamus would write a poem. That changed everything for me. Anything the Heaneys were cool with, I was cool with. They were my idea of what a dazzling couple ought to be, and they were always, always kind to us, and we needed kindness.

When Seamus stood up and read the poem, “Baptism: for Ellen and Kate Flanagan,” I accepted everything—all of it, all at once: poetry, God, and myself.

For half a century, I’ve kept the piece of onionskin he typed that poem on, so thin that it’s almost translucent. It’s a blessing on the long, strange project of being Kate Flanagan. That winter night in Dublin, Seamus gave me the one thing I desperately needed growing up in that crazy family: my certificate of belonging, in this world and the next.

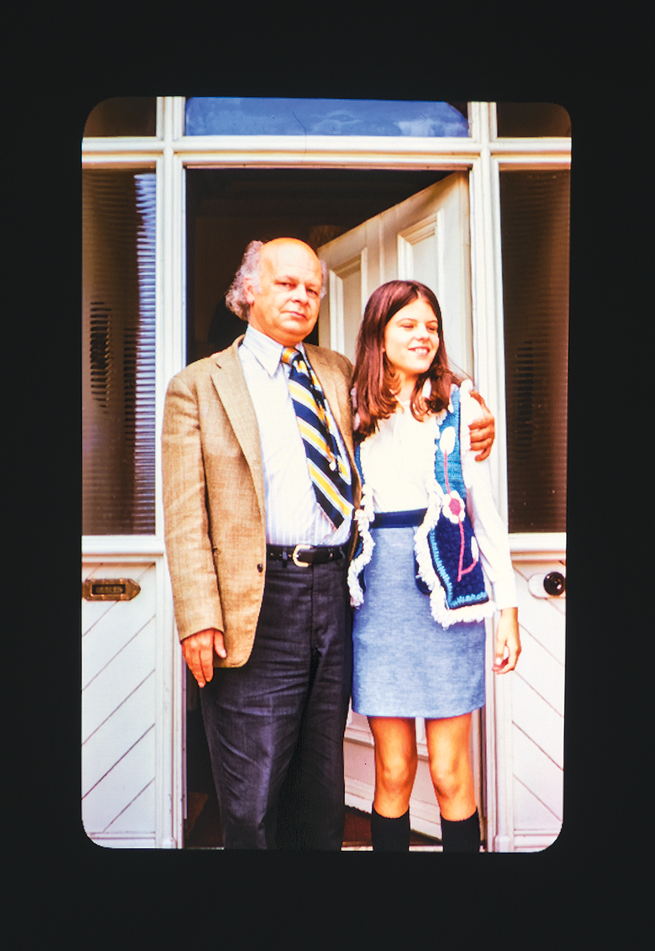

We first met the Heaneys the year before the baptism, in 1970, when I was 9 years old. Seamus, Marie, and their two little boys, Michael and Christopher, had come to California so that Seamus could spend the academic year in the UC Berkeley English department. (Their daughter, Catherine Ann, was still circling in the future, choosing her moment.) My parents were almost 20 years older than the Heaneys, my father a professor in the department, and they took the family under their wing as they did for many visiting professors—Jean in her motherly way, and Tom with his incredible erudition and merciless, legendary wit.

“Berkeley swings like a swing-boat, has all the colour of the fairground and as much incense burning as a high altar in the Vatican,” Seamus wrote to his editor, Rosemary Goad, shortly after arriving. That wonderful description spent 50 years in a folder, but now—on the tenth anniversary of his death—has been published in the collected Letters of Seamus Heaney, edited by the poet Christopher Reid. Of course I’ve read and loved Seamus’s poetry most of my life, but the way I actually knew him was in person, talking with people. Every joke, kind word, and cynical quip expressed in the letters—many of which mentioned or were addressed to my father—made me feel that he was in a room just beyond the one where I sat reading.

One Heaney is fun. All of the Heaneys together are the best time you’ll ever have. Marie is smart and beautiful and funny, and the boys, then 4 and 2, were incredible, with their Northern Irish accents, their serious first names (in America, they’d have been Mike—even Mikey—and Chris), and their fealty to each other. While Ellen was grinding it out in ninth grade—expectations were higher for her, owing to birth order and the obvious fact that she was giving education much more to work with—my mother was blessedly eccentric about my own school attendance. I would report mild health problems and head out with Jean and Marie and the boys on field trips to the pumpkin patches in Half Moon Bay, my mother fearlessly navigating our Plymouth Valiant up and down San Francisco blocks so steep that you would feel the front tires inching across the asphalt until suddenly the center of gravity shifted, physics took over, and for 30 seconds, your fate was anyone’s guess.

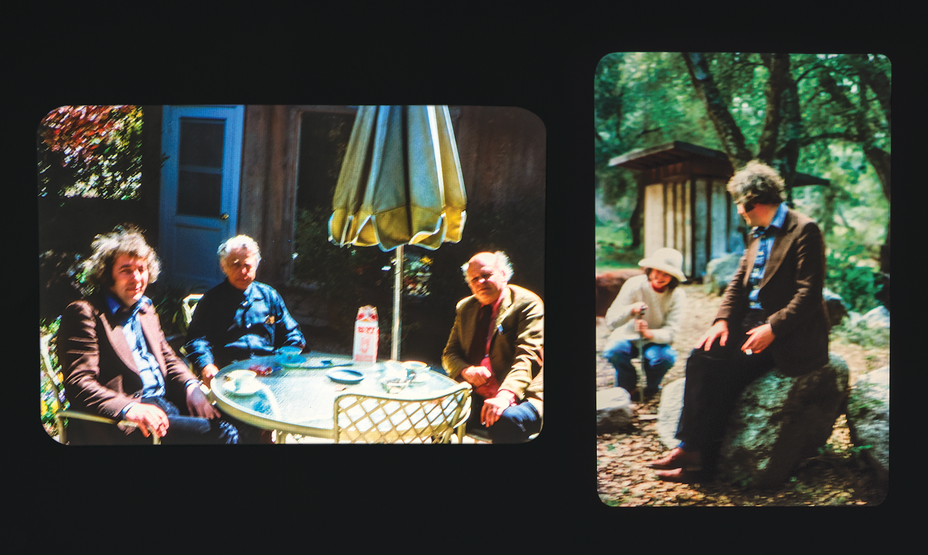

The family wasn’t in Berkeley long before Heaneymania broke out. Berkeley in those days was an archipelago of dinner parties, and my parents were no pikers. There were many mornings when I’d go downstairs to watch cartoons and find Seamus asleep on the couch—he would have driven Marie home to relieve the babysitter and come back so he and Tom could talk and talk, cracking each other up and also taking part in what Seamus would later call the beginning of an ongoing tutorial. If you wanted to discuss Irish history and literature, Tom Flanagan was your man.

Imagine being liberated from Belfast in 1970—when the violence and terror of the Troubles ran in parallel with the most narrowly defined social conventions, policed every hour of the day and night by neighbors, teachers, priests, and ministers—for a year in Berkeley! The contrast was as stark as any between two Western cities could possibly be. This wasn’t London, where King’s Road offered velvet pants, joss sticks, and a friendly attitude toward sex between strangers as a thriving, but still circumscribed, performance. This was a citywide retreat from the known social order, with a California twist.

Early mornings, Seamus would sometimes drive the family across the bay to Sam’s, in Tiburon, for pancakes and champagne, getting home in time to teach his 9 a.m. class. Their first weekend in town, the family went to a Pete Seeger concert. At parties he met the great California poets—Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder. He and Leonard Michaels became friends. His one regret when they arrived was that he’d gotten his hair cut before leaving Ireland.

“It’s lotus land for the moment,” he wrote to friends—a perfect Seamus sentence, suggesting both his ease with the sensual experience of California and his sly, characteristic caution: for the moment. All too soon, from my perspective, the year ended, and the Heaneys packed up their flat, said goodbye to champagne and pancakes, and headed home to Belfast. As Seamus would say, “Back to porridge and gunfire.”

We Flanagans wouldn’tbe far behind the Heaneys, because my father’s sabbatical year was upon us. Once Ellen and I had re-enrolled at our Dublin school and settled back into our Irish life, we drove north to spend a week with the Heaneys in Belfast.

Of course I knew about the Troubles, but I’d never seen a militarized border before. Tom warned us to be quiet while an officer took our passports and inspected the trunk of the Morris Mini for weapons. Our mother was at the wheel because Tom refused to learn to drive a car, while Ellen and I sat in the back seat, staring out anxiously from beneath a welter of books and the glinting gold wrappers of a dozen Cadbury Milks. A few soldiers (“They’re so young,” my mother said) watched us in a wary and—in the manner of all soldiers on shit deployments—contemptuous way. The mystified officer who waved us through seemed to figure that we were creatures of extreme naivete who would be dealt with, one way or another, once we were in Belfast.

The country roads were beautiful, but terrible things happened on them. For two decades, the most frightening sound in the north was the screech of brakes preceding a bomb being thrown through the doors of a dance hall or pub. The “proxy bomb” was created during the conflict, such a well-designed instrument of terror that it was later deployed as far away as Colombia and Syria. Gunmen stop a driver on a country road and force him to get into the driver’s seat of a waiting car that has been loaded with a bomb. He will drive that car into whatever target he’s told. The gunmen’s leverage is absolute: They have the man’s family at gunpoint back at the farm—perhaps they will remind him of what the children were wearing that morning.

I remember that Seamus was haunted by an incident in which a van full of workers was stopped by masked men, who demanded that everyone get out and stand in a line. The Catholics were ordered to come forward. In fact, only one of the men was Catholic. The man next to him secretly took his hand and pressed it: Don’t do it; we’ll cover for you. But for whatever reason, habit or loyalty, he stepped forward—and all of the others were swiftly machine-gunned. The ambushers were Catholics.

In Berkeley, one of Seamus’s Black friends once asked him to explain what was happening in the north of Ireland, and when he’d finished a brief accounting, his friend said, “I don’t know the words, but I sure recognize the tune.” It was the old thing, the thing that people do to one another. And as the violence continued, the threads holding the tapestry together started to snap.

Belfast frightened me, but once we got to 16 Ashley Avenue, nothing bad could happen. It was like a family reunion. Ellen and I watched The Magic Roundabout with the boys, and every night at dusk, Seamus and the other men on the street would unroll concertina wire at the ends of the block.

One evening, the adults were planning to go to a party while Ellen and I watched the boys—the babysitter had backed out. Ellen was extremely beautiful and getting more so by the month. My parents didn’t seem to care that their teenage daughter was stuck at home, fed a constant diet of Seán Ó Riada and the Irish rebellion of 1798, but Marie did. Other young people would be at this party, and Marie many times said it was a shame that Ellen couldn’t go too. I was determined to save the night, and I insisted that I would be the babysitter. Everyone thought it was a weird idea—no one more so than the little boys—but I’m an adamant person. Marie told me that I could call her at the smallest hint of trouble.

Everyone left, the boys got into their pajamas, and we hit the Richard Scarry pretty hard. Soon they were asleep. I felt amazing and useful and like a teenager myself. But after about an hour, I started hearing noises—muffled booms, shouting. Perhaps they were the sounds of any normal city at night, but Belfast in 1972 wasn’t a normal city. I looked in on the little boys, and realized I had taken on more than I could handle. What in the world was I going to do if I had to get them out? In defeat, I called Marie, and she came home. All the rest of my life, I’ve regretted doing it. I could have been the hero; I could have been the Ellen!

Because what was happening in the north was so violent, because it was unfolding in an English-speaking country, because it could be read as an ethnic minority’s final fight against empire, and—perhaps most important—because it involved Ireland, a country from which millions of Americans claimed ancestry, the Troubles quickly became not just a European story but a global one. And because the six counties of the north were filled with children going to school, women shopping, farmers walking cows down tiny lanes to be milked, and young people’s dances and secret spaces, they produced a river of blood.

What did people want from Seamus Heaney at that time? Everything. There was tremendous pressure for him to turn his poetry into a form of opinion writing and take moral command of the situation. He would never have done anything like that. He was a poet, not an on-call political-versification machine. More than that, he understood that what was happening didn’t fit into a neat rubric of oppression and colonial rule. This was a 14-year-old headed to band practice who was abducted, hooded, and murdered. This was an 11-year-old on her way to school when a bomb exploded in her father’s car. This wasn’t an academic debate about the Stormont government or the British army’s casual use of rubber bullets. This was hell.

Seamus in the early ’70s had become very interested in the bodies that had been discovered in the bogs that stretch across Northern Europe. This type of bog has the perfect conditions to preserve bodies for thousands of years. The majority of those that have been found were Iron Age people, and despite their wide geographic distribution, they tend to have commonalities: A great number were naked, except for perhaps a ceremonial piece of clothing or jewelry; their stomachs were filled with a gruel of local grains; and many had been murdered. Some had been staked into the bog with wooden pegs, as though to protect them from theft or interference, or even to offer them as a sort of display.

In 1950, an archaeologist named P. V. Glob, who was employed by a museum in Aarhus, Denmark, oversaw the removal of a body from the village of Tollund—the astonishingly well-preserved corpse of a man killed more than 2,000 years earlier. Glob wrote a book about that find and several others, and he gave it a riveting title: not The Bog Bodies, but The Bog People. Who were they? What did they tell us of their beliefs and their cultures?

Seamus knew bogs well; he’d cut turf on the family farm in County Derry. And he knew the things that had been pulled out of bogs: the skeletons of giant Irish elk, long extinct; clay jars still filled with butter. The Bog People inspired him. Soon after his return from Berkeley, he published “The Tollund Man,” a terrifying abduction of a poem that casually welcomes you on a short journey before grabbing hold of you and taking you right down to the underworld.

“Some day I will go to Aarhus,” the poem begins, like an epic:

To see his peat-brown head,

The mild pods of his eye-lids,

His pointed skin cap.

Already the poem is turning, taking you to the place in the bog “where they dug him out,” wanting to see the “gruel of winter seeds / caked in his stomach.” We are in the territory of Robert Graves and the White Goddess:

I could risk blasphemy,

Consecrate the cauldron bog

Our holy ground and pray

Him to make germinateThe scattered, ambushed

Flesh of labourers

Laborers, brothers, children, old men—the ambushed dead; the missing; the disappeared.

We’re in the underworld now, chthonic and mad, as the townspeople point at the Tollund Man while he is raced in a cart to his murder. How was he chosen? How is anyone chosen?

The famous last stanza of the poem is the answer to the question people didn’t even know how to pose about the river of blood.

Out there in Jutland

In the old man-killing parishes

I will feel lost,

Unhappy and at home.

Seamus often compared his bond with Tom to the one between father and son. “I suppose you’re destined to be a father-figure of sorts to me,” he wrote to Tom in 1974. “Blooming awful.”

Seamus had a father, of course, the farmer and cattle dealer Patrick Heaney. But Tom was his “literary foster father.” In the year that Seamus arrived in California, he later told an interviewer, his “head was still basically wired up to English Literature terminals.” It was Tom, he said, who gave him a “far more charged-up sense of Yeats and Joyce” and the “whole Irish consequence.”

Seamus was a poet in a country known for them. My father often said that Seamus came early into a sense not merely of his talent, but also of the obligations that went along with it. But he didn’t necessarily want to be a poet of the madness unfolding in the north. Of the Tollund Man he later said: “Even if there had been no Northern Troubles, no mankilling in the parishes, I would still have felt at home with that ‘peat-brown head’—an utterly familiar countryman’s face.”

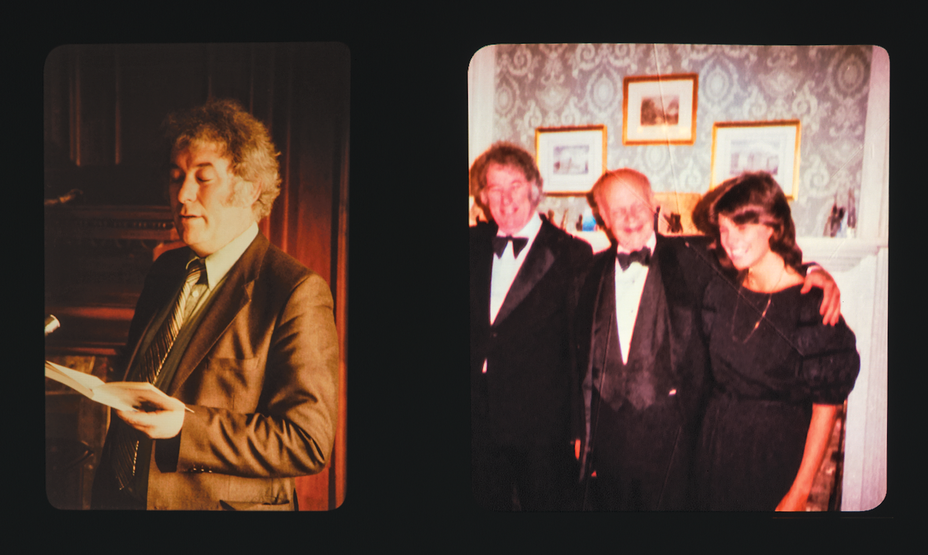

Even as a global figure, Seamus never stopped being grateful to Tom for playing what he saw as an essential role in his development as an artist. In the collection of letters, I came across one he’d written to a friend soon after Seamus had accepted the Nobel Prize in Stockholm. He and Marie were in New York, where they’d driven the two hours to my parents’ house on Long Island—“a chance to see Tom and Jean Flanagan and sit with them in gratitude and sage memory, friendship and wonder at what can happen to a youth from the fields.”

As the years went on, Seamus quietly took care of all kinds of needs that Tom had. One year we lived in Ireland in a rental house that had the basics, including a set of cheaply made but brand-new furniture. What it didn’t have was a bookcase. Tom was working on a novel, and his office looked like a graduate student’s squat until Seamus showed up with wood and nails and stain, and built my father a bookcase.

Near the end of Tom’s life, when he was becoming frail, my parents bought another house in the Berkeley Hills, and Seamus came out to see it. My father was anxious to show him the impressive study, which ran the length of the house in a gabled attic. It was a magnificent space but had a very steep staircase, and the second Seamus saw it, he said my parents had to get a banister put in.

My mother (a former nurse and essentially the breathing apparatus of one Tom Flanagan) had of course been saying that since the day they moved in, and my father (pretty much the hair shirt of one Jean Flanagan) had ignored her. Each time she raised it anew he would say, “Banister, banister, awk, awk,” like she was a parrot in a cage. (I’m telling you, this was one of the world’s great marriages crammed with enough nuclear-level rage to split the world apart like two plates.) But when Seamus said “banister,” my father got the banister.

I used to think that my father was my ace in the hole. He had the same handwriting as Santa Claus, who was, of course, God. He was at absolute ease in any group of great thinkers and writers, and because of him, I grew up around many remarkable people. Sometimes when we were talking, he would say, “That’s a good point,” or even “That’s a very good point.” He never said it to jolly me along; he said it when I’d made a good point. To this day, if you were to observe me thinking—while gardening or cooking or waiting in the TSA line—you might hear me mutter, “That’s a very good point,” and at first opportunity, I’ll go write it down.

Why would a girl with such a wonderful father ever need a second one? Because someone must have dropped Tom on his head as a baby. A streak of cruelty ran through him that could be channeled into incredibly destructive behavior, sometimes directed at himself, more often at the three people he loved most: my mother, my sister, and me.

If you had caught up with me 20 years ago, or even 10, I would have showered you with shocking tales. But something happens when you turn 60. You just let go. You finally realize there isn’t ever going to be a reward for thinking about something and talking about it. And you realize (terrible truth though it may be) that, as Philip Larkin—of all people!—reports, “what will survive of us is love.”

One of the many things I inherited after my father’s death was Seamus’s loyalty. My parents died within a year of each other. Hardly a tragedy: I was almost 40! But who has ever been closer to their difficult parents? My position in the family was that of a suitcase to the traveler. Half of the time it’s an unholy burden, but when you see it thundering back down the luggage chute, you could weep with relief. I was deeply loved, and I was never left behind.

Six months after Tom died, I was suddenly diagnosed with aggressive and life-threatening breast cancer. I felt a strong need to keep the information contained to as small a group as possible. I thought it would hurt my career if people knew I was that sick, and also, in a primitive way, I thought that the fewer people who knew about it, the better the chance it wasn’t real. But somehow Seamus found out.

So many of Seamus’s letters in the collection begin in apology—over and over again, he makes amends for being so egregiously late in responding to someone. And yet, not 10 days after the diagnosis, a letter arrived from Seamus and Marie. They were aghast at the completely “arbitrary insult upon health and beauty.” Soon after, another letter: He’d heard I’d come through surgery, “as valiantly and gracefully as the great spirit you are and have been.” They would be in St. Lucia for 10 days—probably to visit their friend, the poet Derek Walcott—and he told me how to reach them if I needed them.

Everyone who knew Seamus has a story like that. He had a sense of obligation to others that in anyone else would be incapacitating. Once, when my own children were small, I took them to visit Seamus and Marie. After tea and hugs, we climbed into the taxi, and the driver said, “So you’ve been to see the great man.” Almost around the corner was a billboard with his picture on it, promoting a new documentary. By his later years, there was no escaping himself, and the endless duties the role entailed. He may have fantasized about ditching those duties, but he never shirked them.

The letters helped; the poems too. After I first got sick, and in the years since, I have returned often to some of his most famous lines, from The Cure at Troy, which argues for faith in an unseen future. Seamus didn’t believe in a force as mere as optimism. He believed in something far greater and more powerful: hope.

So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that a further shoreIs reachable from here.

Believe in miracles

And cures and healing wells.

It was because of those lines that I started ignoring the oncologists who insisted that I would never be cured.

When a public person dies as suddenly and shockingly as Seamus did—on an ordinary August morning in 2013, in a hospital corridor on his way to surgery—before the family has an hour to confront the unthinkable, the news flies out the window and circles the world. It was an international story, of course, but in Ireland, the grief was personal, intense, self-reflective.

Whatever it means to be Irish—whatever qualities of heart and mind, whatever generosity and love for the very earth and rocks of that island—millions of Irish people were convinced that Seamus Heaney embodied it. All over Ireland, the grief was not just for a storied Irishman and a great poet. The grief was for a friend.

Two days after he died was the All-Ireland football semifinal. Dublin versus Kerry, no kidding around, and 80,000 people packed into Croke Park. Before the match, a photo of Seamus appeared on two giant screens, and almost unthinkingly, as though rising for “The Soldier’s Song,” everyone in that stadium stood up. The announcer said: “We’d like to mark the passing of one of our greatest literary icons, the Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney.” And with that, the entire crowd began clapping. The announcer said that in addition to his great works and awards, Seamus had played underage football for Castledawson in Derry. The weight given to that last fact was the same as to the first ones. It meant: He was one of us. Among the sacks of letters to The Irish Times was one written by a man called Frank Munnelly: “As a nation we are a man down.”

The funeral was in Dublin, and the burial was in Bellaghy, and the roads were lined with people. Seamus had read his poetry around the world, and been welcomed everywhere, but he never had any doubt about where the journey would end: in the graveyard of his parish church. “We are welcoming Seamus home,” said the parish priest, while 2,000 mourners strained to hear him. The family was there, of course: those children of the father who had never once failed them and had only and always loved them, and, in the center of everything, always—Marie. Michael (now Mick) spoke briefly, informing the world of Seamus’s last words—a text to Marie that read, “Noli timere”: Don’t be afraid.

My parents don’t have graves. We were a very anti-death family. They had both suffered devastating losses when they were children, and so they tried to keep the very notion of death a secret from us for as long as possible. When Ellen texted me, “Have you heard about Seamus?,” I knew it could mean only one thing. But for a minute or so I stopped myself from Googling his name. I was giving reality a chance to sort itself out. My rational self reported that if he was dead, then there would someday be a grave and a gravestone, and I instantly decided that if that was true, I would never go see them. It would be an acceptance of a fact I was fighting against.

But a few months ago, a full decade after he died, I went at last to Bellaghy. My husband took me—“Stalwart Rob,” as my father described him in his last letter to Seamus—and we sailed over the “invisible border,” as it’s now called. There’s no more signage than there is crossing a state line in America—in fact, none at all.

The sky was darkening because we were late; we’d been having lunch with Marie and Mick in Dublin and hadn’t wanted to leave. We arrived at St. Mary’s church under a spitting rain that would suddenly let up, in bursts of revelation and transfiguration, as Irish rains do. Halfway down the graveyard, dark marble austere against the hard gray of the church wall, the headstone seemed almost to hover a few inches off the earth because of the famous line carved into it: “Walk on air against your better judgement.”

It’s from a poem, “The Gravel Walks,” and it gives you the ability, the permission, to hold the full, complicated equation of life lightly. I repeat it often. I’ve been sick for many years now, and whenever I get a call that explains some bad finding, I listen stoically and then remind myself that I’ll walk on air despite the news.

The words are for the world—ours and that of future generations—but most of all, I imagine them as a private communication to Marie. The point of the entire operation was always Marie, the quarry turned way of life.

I’d bought three pots of violets at SPAR market, in the village, and I put the flowers next to the gravestone, feeling a bit sheepish, as though I was performing something I’d learned from the movies, or television, though Seamus—and Tom, come to think of it—would have approved of SPAR market. It was the right way to go about it.

I was inclined to stay there forever; why else had I come? But it was getting cold, and Rob gently kicked at some of the gravel in the path between graves.

“The kingdom of gravel was inside you,” the poem says. “Hoard and praise the verity of gravel. / Gems for the undeluded. Milt of earth.” And yet that’s the poem that ends in air, with the gentle counsel to establish yourself “somewhere in between” the earth and heaven, the gravel and a song.

Then, just past where Rob was standing, I saw a much older headstone, weathered, but its letters clearly read HEANEY. And, in smaller print, beneath:

Erected by Patrick Heaney

In Memory of his son Christopher

Died 25th Feb. 1953 Aged three years.

It jolted me in a way Seamus’s grave hadn’t. Christopher was Seamus’s little brother, who ran into the road and was struck by a car and killed. “Mid-Term Break”—one of the first poems people read when they discover Seamus’s work—is about Seamus receiving the news at 14, when he was away at boarding school, and then coming home.

In the porch I met my father crying—

He had always taken funerals in his stride—

Seamus hated crying—“blubbering”—and I always wondered if this terrible scene was a reason for that.

The baby cooed and laughed and rocked the pram

When I came in, and I was embarrassed

By old men standing up to shake my hand

A child dead, and a sudden manhood foisted upon Seamus. His early poems are so familiar to me that the events they record can seem like the ones in fiction, the responses of the speaker those of a fictional character. But there was Christopher’s grave, just as real as his brother’s, just as much a marker of a human life.

I’ve been a Catholic since my baptism, but the only Catholic tradition I remember my father handing down to me was lighting a candle “for the dead of the family.” Catholicism provides you with something no rational approach to the world ever will: a cosmology of intercessors, saints. It’s a religion that acknowledges, openly and from the very beginning, that faith itself is a mystery. Walking out of that graveyard left me with a bleakness, but I didn’t have time to confront it, because I was already entering the church so that I could light a candle for the dead of my family.

We can’t escape it: losing the people we love and need the most. Each death has to be countenanced as a fact, squared away in the record books. But there are people so well known to us, so loved, that death is one more thing that can be turned to air.

When Tom died, Seamus wrote an obituary for him in The New York Review of Books : “Since our first meeting in 1970, he was like a father to me and like a typical Irish son I felt closest at our times of greatest silence and remoteness.” He described a few of their endless car trips and excursions; only Tom and Seamus would scramble down a cliff path in Antrim to see the site where Roger Casement had wanted to be buried. Let no stone be unturned, no vigil unattended. And then Seamus quoted the poem he’d written at the time of his own father’s death:

And there was nothing between us there

That might not still be happily ever after.

This article appears in the January 2025 print edition with the headline “Walk on Air Against Your Better Judgment.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.