America’s Oldest Black Rodeo Is Back

10 min read

Boley is easy to miss. The flat vista of eastern Oklahoma is briefly interrupted by a handful of homes and some boarded-up buildings, the extent of the tiny town. In its heyday, Boley was a marvel of the Plains, a town built by and for Black people that attracted visitors and media attention from across the country. But now its businesses are defunct, and the steady outflow of young people has left behind an aging population of only about 1,000 people. The main reminder of the town’s glory days is the historical marker I passed on Route 62. The road took me to the wide-open fields where the Boley Rodeo, hailed as the oldest Black rodeo in America, is held every year. I arrived at the grounds early on a May morning, before the sun pierced the clouds. Karen Ekuban, the rodeo’s promoter, had already been there for hours.

The rodeo was in two days, and Ekuban and a small crew of volunteers, including her children, had been busy. She was obsessing over every detail. When new bleachers had been installed a few days earlier, she’d spent so much time directing workers to ensure that the earth underneath them was level, with no holes where people might trip, that she’d dozed off as she drove home that night. Instead of veering into traffic, her vehicle had eased onto the shoulder, jolting her alert. Ekuban told me the story with a giggle, as if nothing had happened. She was “awake now,” she said.

The annual rodeo had been a Boley tradition for more than 120 years, once regularly drawing crowds of thousands, but as of late, it had become something of a glorified family reunion for people with ties to Boley. Ekuban had a plan to try to turn that around. She’d sunk thousands of dollars of her own money and months of her time into throwing what she hoped would be the best rodeo the town had ever seen. Her goal was to raise at least $200,000 to help revitalize Boley, and bring back national attention to the town.

Without much in the way of a budget, Ekuban created a new sign to welcome the visitors she hoped would come for the rodeo. Ekuban’s new logo for Boley featured a silhouette of a cowboy on a bucking bull. She also brought on Danell Tipton, a world champion bull rider, to serve as the rodeo’s producer.

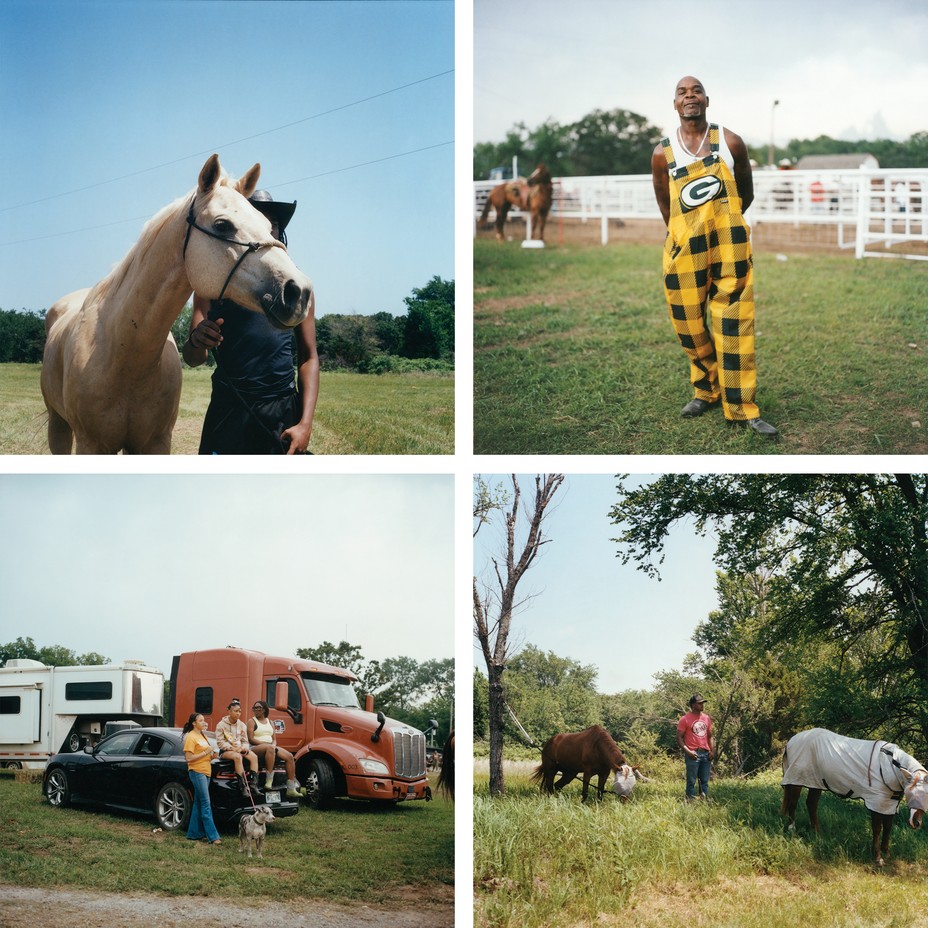

Members of the community turned out to help. Henrietta Hicks, an 89-year-old judge whom Ekuban affectionately refers to as “Grandmother,” offered her home to Ekuban the night of her near accident. Other old-timers and close friends stopped by to lend a hand. I watched as they worked up a sweat, carrying provisions that they hoped would feed thousands of visitors. All the while, Ekuban’s phone chimed, sending a notification for each ticket bought online. As the sun set, a caravan of trailers carrying horses and bulls arrived.

Ekuban’s aspirations for the rodeo echo the ambitions of her forebears. In 1866, a year after the Civil War ended, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation signed a treaty with the United States. In that agreement, all Black people who had been enslaved by the Muscogee Nation were emancipated and provided with full Creek citizenship privileges, including the right to landownership. (The Muscogee Nation would later redefine citizenship to exclude the descendants of those enslaved people, a decision that some descendants are challenging in court.) Abigail Barnett and her father, James, a freedman of the Muscogee Nation, were deeded the land that would become Boley, and many other Black Creek citizens settled nearby. After the arrival of the Fort Smith and Western Railway, in 1903, J. B. Boley, a white railroad agent, helped the community incorporate, a process completed in 1905. According to the historical marker in town, Mr. Boley had faith in the Black Man to govern himself and persuaded the railroad to establish a townsite here.

In those days, Oklahoma was promoted by a network of boosters as a promised land for Black people, part of a larger movement to establish Black autonomy and self-governance throughout the West. Some 50 Black towns popped up across Oklahoma from 1865 through 1920. This movement was closely associated with the work of Edward McCabe, who’d risen to prominence when he became the state auditor of Kansas, the first Black person to be elected to a statewide office in the West. McCabe moved to the Oklahoma Territory after two terms in office, hoping to make it a majority-Black state. In an 1891 speech, he laid out his vision. “We will have a new party, having for its purpose negro supremacy in at least one State,” he said, with “negro State and county officers and negro Senators and Representatives in Washington.” Answering the summons of McCabe and others, thousands of Black people chose to forsake the dominion of Jim Crow for Oklahoma.

The very existence of Boley, and other towns like it, proved what was then—in many white people’s minds—a radical proposition: that Black people could thrive on their own. Booker T. Washington visited the town in 1905 and marveled at its two colleges, its abundance of land. Unlike in other Black communities in America at the time, many of which struggled, the original guarantee of citizenship and property rights in Boley under the 1866 treaty gave citizens a measure of security and wealth to pass on. Even decades after Boley’s founding, the allure of freedom and the ability to own the land under their feet drew Black families—including Ekuban’s Mississippian parents—from across the South.

The exact origins of the Boley Rodeo are lost to time, although we do know that it likely arose organically from local customs that predated the town itself. Rodeo, descended from practices established by Spanish and Mexican ranchers, had been molded into its modern form through the participation of Black cowboys, and Boley’s iteration formalized it locally as an event. Even in its early days, the Boley Rodeo regularly drew spectators of all races from Oklahoma and elsewhere, and inspired several other rodeos across the South and the West. One year, Joe Louis, the legendary boxer, made an appearance. The rodeo was always an important source of income for the town.

The 1960s marked the heyday of both Boley and its famous rodeo. According to The Black Dispatch, a newspaper in Oklahoma City, at least 10,000 people attended the event in 1961. The rodeo that year featured acts such as Billy “The Kid” Emerson, a Black rock-and-roll pioneer, and a full orchestra from Houston. In 1963, the same newspaper noted the growth in the “small Negro metropolis,” marked by the five new businesses that had sprung up on Main Street.

But as has been the trend in much of rural America—particularly Black rural America—Boley has suffered from the loss of capital and the gravitational pull of city life. In recent decades, many young people left in search of opportunities elsewhere, and the elders who remained struggled to keep the memory of the old days alive. Boley’s self-reliance had been lauded by white politicians and business executives, but when the town struggled, they lost interest, leaving it to wither.

Over time, the rodeo faded as well. Before Ekuban pitched her plan, it seemed possible that the rodeo might disappear entirely, and that—in a state where history books rarely mention places like Boley—the history might disappear too. Even with Ekuban’s intervention, there are no guarantees.

Ekuban left Boley after high school, some 35 years ago, with no interest in returning. But she eventually discovered that the place had a hold on her. Her mother had taught for decades in the now-defunct school, and her father had served as superintendent. Ekuban remembers how sporting events were held at the local prison, one of the town’s main employers, because there were no facilities elsewhere. When she returned to the area, she bought a house in nearby Spencer, another majority-Black town in Oklahoma. Ekuban started several revitalization projects, because she wanted to cultivate the beauty she saw in her hometown. But after she learned more about Boley’s history from “Grandmother” Hicks, Ekuban’s says her desire to help took on new significance.

She wanted to impress that significance upon the rodeo’s supporters, and to explain just why its success was important. So, the day before the rodeo, even with plenty of setup work left to do, Ekuban gathered a group of friends and family members. They drove to Tulsa to visit the Greenwood Rising History Center, which commemorates Tulsa’s Greenwood District, a neighborhood that had been established by Black people as part of the same wave of migration that built Boley. Greenwood was a thriving community that grew so prosperous, it gained national fame under the moniker “Black Wall Street.” But in 1921, a mob of white assailants attacked and burned the district, killing as many as 300 Black residents and leaving thousands more homeless. The massacre was a tragic reminder of the limits of the optimism of boosters like McCabe, who believed that a Black state could offer “equal chances with the white man, free and independent.” But the exhibition also shows that, even if only briefly, the exertions of Black people themselves brought McCabe’s vision to fruition.

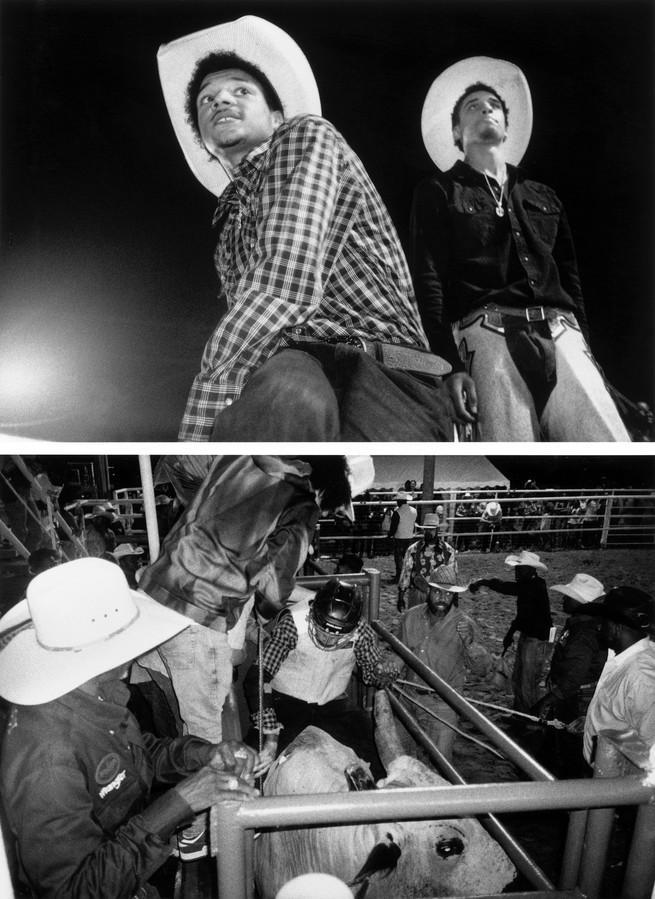

In front of the exhibits showcasing the golden age of Black Oklahoma, Ekuban told the crowd how early Boleyites had journeyed hundreds, in some cases thousands, of miles to unfamiliar territory, and then dug, carved, and heaved their way to independence. They built schools, gristmills, homes, universities, churches, and hospitals. They bore children, and one generation passed down its story to the next. Part of that story was the Boley Rodeo. For more than a century, cowboys had sought to ride atop the bulls and broncos as long as their will and body would allow. They did this for money and acclaim, yes, but also for a less tangible reason: because, no matter how many times they were knocked off their horse, dusted up, and trampled on, trying was always their salvation.

By the morning of the rodeo, Ekuban had sold more than 1,400 advance tickets, and she hoped thousands more would purchase admission at the gate. She’d already banked more than $20,000 from ticket sales.

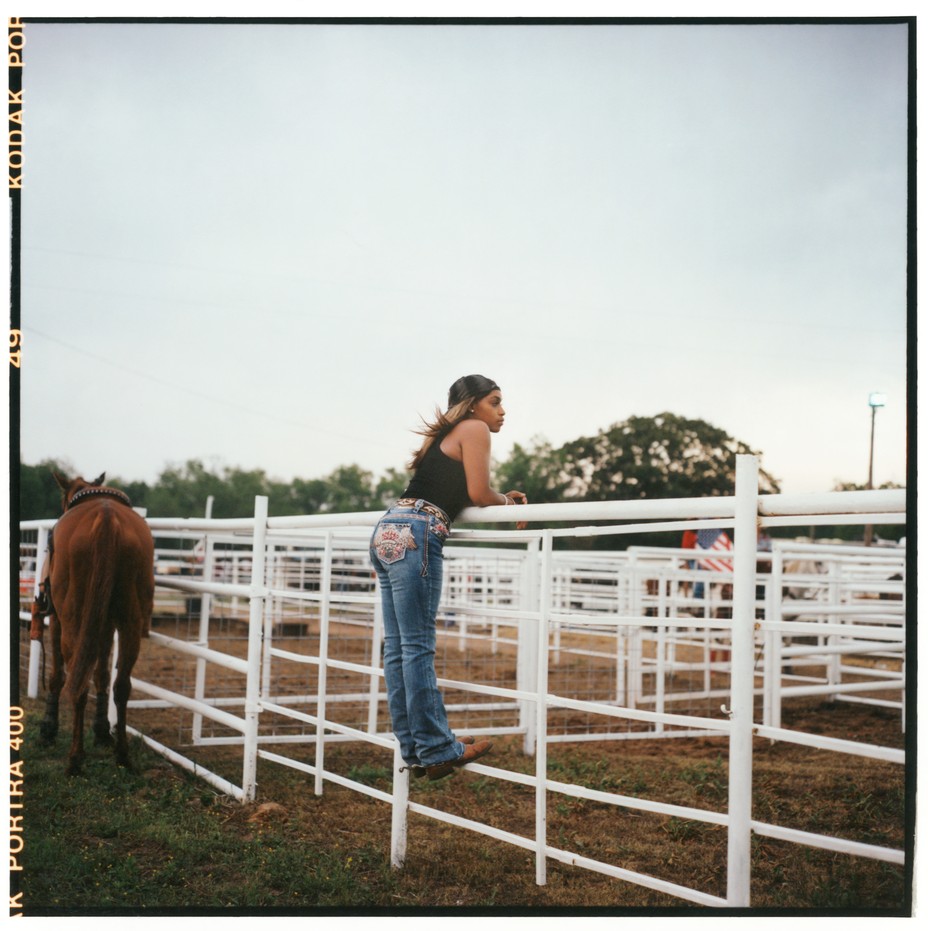

A parade of souped-up classic cars, followed by dancing, flag-waving spectators, opened the event. Willie Jones, a country singer who was featured on Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter album, performed. And then, at 7 p.m., the cowboys entered. The gates to the east of the arena opened and the horses galloped through, kicking up huge clouds of dust.

For the first time in weeks, Ekuban breathed easy. If only for a moment, she could return to the wonder she had experienced as a kid. But then, just 30 minutes into the rodeo, she spoke with her husband, whom she had appointed to liaise with local police and security. Attendance had surged to more than 5,000 people. Without enough seats, some spectators were hanging on the white railing of the rodeo arena. Ekuban had to tell her husband and the police officers to close the gates to the rodeo grounds.

As the sun set, young cowboys proved their mettle by riding half-wild broncos, the muscles of both man and beast straining to prevail. When the bulls came out, the competitors traded their cowboy hats for padded helmets. Away from the action, Ekuban watched as attendees bought merchandise from stands run by her fellow Boleyites.

Finally, it was time for the centerpiece of the rodeo: the Pony Express, a relay race on horseback, a tradition unique to Oklahoma rodeos. In the finals, the Country Boyz faced off against newer competitors, the Yung Fly Cowboys. Four riders from each team lined up, whispering in their horses’ ears.

The gun fired, and the competitors took off. Riding half-ton horses, they went around the track furiously. The Yung Fly Cowboys finished first, unseating the Country Boyz as champions. In a moment that might have seemed strange at any other rodeo, the stereo system swapped out the country music that had been playing all day for “Get in With Me,” by the Florida rapper BossMan Dlow. The winning crew’s music blared, and winners and losers alike recited every lyric.

The rodeo was over.

Today, with the success of Cowboy Carter, with the breakthroughs of Black country artists such as Shaboozey, with the growing prominence of Black rodeos including Bill Pickett’s Invitational, and with increased awareness of the Greenwood District through vehicles like the HBO miniseries Watchmen, it’s easier than ever to see the Boley Rodeo’s legacy. In popular culture, the mélange of Westerns and cowboys and country music that is often called “Americana” has been associated with a particular vision of liberty, in which the people most entitled to the possibilities of the West are white men who mastered the land and its inhabitants. But Boley and its rodeo helped create a countertradition—that of the Black West. In this tradition, Black people who had every reason to give up on America instead struck out for places like Boley and dictated the terms of their belonging.

The Black West is a compilation of stories often overlooked or forgotten. As someone from Oklahoma, I’ve long wondered why our histories—of rodeos and of the dreams of leaders like Edward McCabe—don’t appear in many mainstream depictions of Black life. It is our obligation to salvage and reimagine these remnants.

When it was all over, Ekuban had sold about 3,500 tickets to the revitalized rodeo, and had raised more than $270,000 from ticket sales, donations, sponsorships, and investments. She deemed it enough of a success to start planning the next one before the spectators had even left. It remains unclear whether the rodeo can actually attract enough money to save Boley, but the event undoubtedly helped spread the word about the town’s history and culture, and that was, in itself, a kind of victory. I was surprised when Ekuban, an eternal optimist, seemed to acknowledge how quixotic her mission is. “Boley will never be what it was,” she told me, then added: “But who says it can’t be better?”

This article appears in the January 2025 print edition with the headline “Boley Rides Again.”