RIP, the Axis of Resistance

6 min read

Iran’s Axis of Resistance, an informal coalition of anti-Western and anti-Israeli militias, was already having a terrible year. But the loss of the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad may have dealt the knockout blow.

Syria was both the organizing ground and the proof of concept for the Axis. Assad owed his throne to its armies, which helped him kill hundreds of thousands of civilians in the civil war that began in 2011. Unlike other members of the Axis, Assad wasn’t an Islamist. He also had real differences with Hamas (the only Sunni member of the Axis) and the Yemeni Houthis. But other than Iran itself, Syria was the only United Nations member-state to be considered part of the Axis, and its territory was crucial. Iran passed supplies through Syria to Hezbollah, in neighboring Lebanon, and used it to gather its multinational, mostly Shiite armies of militants from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and elsewhere.

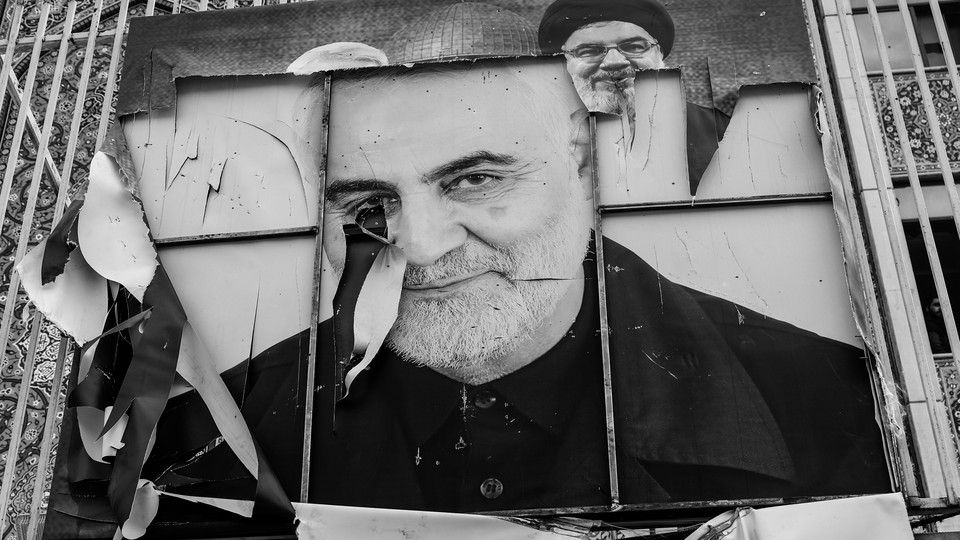

The Axis has come under pressure before, but never like this. In 2020, an American drone killed Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the expeditionary arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the Axis’s fabled leader. The Iranian regional project suffered a blow then, but a survivable one. In a rousing speech at her father’s funeral in Tehran, Soleimani’s daughter Zeynab promised that three of her honorary “uncles” would exact revenge for her father’s death: the Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, the Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh, and Assad. Within the past four months, all three of these avengers have been dispatched from the scene—Haniyah and Nasrallah killed by Israel, and Assad now a refugee in Moscow.

With Assad gone, Iran faces a reckoning. Why did it spend tens of billions of dollars and thousands of lives on a regime that collapsed like a house of cards? Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, delivered a defiant speech last Wednesday, insisting that the Axis was alive and well. He chalked up the fall of Assad to an “American-Zionist plot” and said that Tehran would have saved his regime if it could have, a significant admission of his own regime’s weakened capacities. He called on his supporters to “not fall into passivity” and pledged that the “resistance” would yet expel the United States from the region and “uproot Zionism, with the grace of God.” But Khamenei’s bravado isn’t fooling anyone. Israel had already battered the Axis, and Syria’s Turkey-backed Sunni Islamists have completed the job. Khamenei is barely able to respond to Israel’s repeated attacks on Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, and even Iran itself. His policy has failed.

The end of the Axis is good news. Iranian-backed militias have brought little but misery to the region. They’ve undermined the sovereignty of several Arab countries and intensified religious hatred and sectarianism. Iran’s rulers once claimed to offer an exportable Islamist model that could rival both capitalism and communism. But then they went and governed their own country as a corrupt and repressive oligarchy, giving the lie to such pretenses. All that remained to unite the Axis members was the quest to destroy Israel. As a result, instead of building a better life for their constituents, the Axis members made their countries into Iranian beachheads in a shadow conflict with the United States and Israel.

Iranian leaders often boasted that they controlled four Arab capitals (Damascus, Beirut, Sanaa, and Baghdad). Last week, the Axis lost Damascus. The others are also slipping from Tehran’s grip. In Beirut, Hezbollah has lost many of its field commanders in its war with Israel, and the Lebanese people are running out of patience with the militia. In Baghdad, Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al Sudani’s government enjoys the support of several Iranian-backed militias, but seems not to feel overly constrained by Iranian interests: Iraq did not lift a finger last week to save Assad, and it has maintained close ties with Western allies in the region, such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. The Houthi-led statelet in Yemen remains profoundly anti-Israel and anti-Semitic, and it continues to threaten international shipping in the Red Sea, but it has always been a local movement with looser ties to Tehran than the other members of the Axis. Finally, recent reports suggest that Hamas has agreed to cede the future administration of Gaza to a committee that would include both it and its rival, Fatah—a sign that just over a year after its murderous attack on Israel touched off the most recent conflagration, Hamas, too, is on the back foot.

But the most important capital to be affected by the fall of the Axis is Tehran. Khamenei’s regional policy was supposed to keep the U.S. and Israel at bay. It appears to have done the opposite. In the past 14 months, Israel has battered the Axis and directly attacked Iranian territory for the first (and second) time. Tehran never even answered the Israeli strikes of October 26, because it knew it had few palatable options for doing so. Its bluff called, Iran is now in a corner. And to make matters worse, next month Donald Trump will return to the White House, likely bringing his policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran back with him.

Khamenei’s 35-year rule over Iran has impoverished and isolated his country while making it ever more politically repressive. His hard-line faction is also politically marginalized at the moment, as both the president and the conservative speaker of Parliament have made clear that Iran’s priorities need to be economic development and making a deal with the West. Some believe that the fall of the Axis might persuade Iran to dart toward a nuclear bomb. But decision makers in Tehran know that this would likely incur a ferocious response from the U.S. and Israel, and they may well prefer to take their diplomatic chances on striking a deal with the new American administration.

Nobody will miss the Axis of Resistance. But the history of the Middle East has demonstrated that the demise of a bad actor is not sufficient to produce better ones. The Axis will leave a vacuum that other unsavory forces could fill. What the affected countries will need to avoid that outcome is a combination of foreign direct investment and the will to mediate their internal differences. The two are linked: Disputes are much easier to solve when all parties have a reasonable prospect of prosperity.

There is a public appetite for this agenda. In 2019, the peoples of both Iraq and Lebanon rose up in movements with two central demands: to end the sectarian power-sharing system that empowered the Axis militias in these countries, and to build effective public services. The most conspicuous symbols of the two movements were their countries’ national flags. These were anti-Axis uprisings, in which Iraqis and Lebanese sought to prioritize their own countries over the Axis’s plans for revolutionary havoc in the region.

Suppose that, following the Axis’s collapse, the region became one of stable, cohesive nation-states that pursued economic development rather than war. The democratic dreams that fueled the 2011 Arab Spring would still remain distant—but Iran’s revolutionary project for the region would at last come to a definitive end.