Vivek Ramaswamy Is Uninvited From My Sleepover

7 min read

I could have been a tech entrepreneur, but my parents let me go to sleepovers. I could have been a billionaire, but I used to watch Saturday-morning cartoons. I could have been Vivek Ramaswamy, if not for the ways I’ve been corrupted by the mediocrity of American culture. I’m sad when I contemplate my lazy, pathetic, non-Ramaswamy life.

These ruminations were triggered by a statement that Ramaswamy, the noted cultural critic, made on X on Thursday. He was explaining why tech companies prefer to hire foreign-born and first-generation engineers instead of native-born American ones: It has to do with the utter mediocrity of American culture.

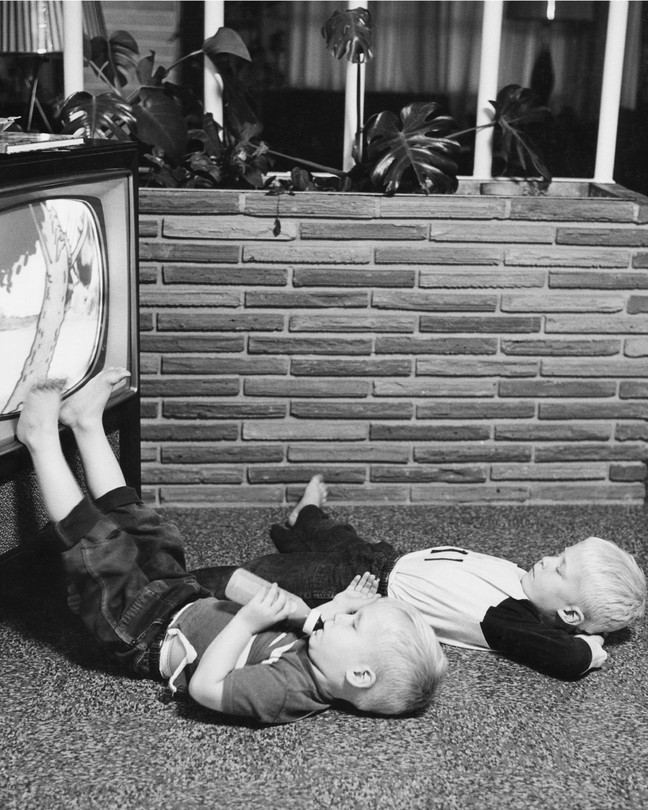

“A culture that celebrates the prom queen over the math Olympiad champ, or the jock over the Valedictorian, will not produce the best engineers,” he observed. Then he laid out his vision of how America needs to change: “More movies like Whiplash, fewer reruns of ‘Friends.’ More math tutoring, fewer sleepovers. More weekend science competitions, fewer Saturday morning cartoons. More books, less TV. More creating, less ‘chillin.’ More extracurriculars, less ‘hanging out at the mall.’”

In other words, Ramaswamy has decided to use the reelection of Donald Trump as an occasion to tiger-mom the hell out of us. No, you may not finish studying before midnight! Put that violin back under your chin this instant! No, a score of 1540 on your SATs is not good enough!

That sound you hear is immigrant parents all across America cheering and applauding.

Maybe Ramaswamy’s missive hit me so hard because I grew up in that kind of household. My grandfather, who went to the tuition-free City College of New York and made it in America as a lawyer, imbued me with that hustling-immigrant mindset. We may be outsiders, he told me, but we’re going to grind, we’re going to work, we’re going to climb that greasy pole.

And yet it never happened for me. I have never written a line of code. Unlike Ramaswamy, I have never founded an unprofitable biotech firm. What can I say? I got sucked into the whole sleepover lifestyle—the pillow fights, the long conversations about guitar solos with my fellow ninth graders. I thought those Saturday-morning Bugs Bunny cartoons were harmless, but soon I was into the hard stuff: Road Runner, Scooby-Doo, and worse, far worse.

As the days have gone by, though, I have had some further thoughts about Ramaswamy’s little sermon. It occurred to me that he may not be quite right about everything. For example, he describes a nation awash in lazy mediocrity, yet America has the strongest economy in the world. American workers are among the most productive, and over the past few years American productivity has been surging. In the past decade, American workers have steadily shifted from low-skill to higher-skill jobs. Apparently, our mediocrity shows up everywhere except in the economic data.

Then I began to wonder if our culture is really as hostile to nerdy kids as he implies. This is a culture that puts The Big Bang Theory on our TV screens and The Social Network in the movie theaters. Haven’t we spent many years lionizing Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Sam Altman? These days, millions of young men orient their lives around the Joe Rogan–Lex Friedman–Andrew Huberman social ideal—bright and curious tech bros who talk a lot about how much protein they ingest and look like they just swallowed a weight machine. When we think about the chief failing of American culture, is it really that we don’t spend enough time valorizing Stanford computer-science majors?

Then I had even deeper doubts about Ramaswamy’s argument. First, maybe he doesn’t understand what thinking is. He seems to believe that the only kind of thinking that matters is solving math problem sets. But one of the reasons we evolved these big brains of ours is so we can live in groups and navigate social landscapes. The hardest intellectual challenges usually involve understanding other people. If Ramaswamy wants a young person to do something cognitively demanding, he shouldn’t send her to a math tutor; he should send her to a sleepover with a bunch of other 12-year-old girls. That’s cognitively demanding.

Second, it could be that Ramaswamy doesn’t understand what makes America great. We are not going to out-compete China by rote learning and obsessive test taking. We don’t thrive only because of those first-generation strivers who keep their nose to the 70-hour-a-week grindstone and build a life for their family. We also thrive because of all the generations that come after, who live in a culture of pluralism and audacity. America is the place where people from all over the world get jammed together into one fractious mess. America was settled by people willing to take a venture into the unknown, willing to work in spaces where the rules hadn’t been written yet. As COVID revealed yet again, we are not adept at compliance and rule following, but we have a flair for dynamism, creativity, and innovation.

Third, I’m not sure Ramaswamy understands what propelled Trump to office. Trump was elected largely by non–college graduates whose highest abilities manifest in largely nonacademic ways—fixing an engine, raising crops, caring for the dying. Maybe Ramaswamy could celebrate the skills of people who didn’t join him at Harvard and Yale instead of dumping on them as a bunch of lard-butts. What part of the word populism does he not understand?

Most important, maybe Ramaswamy doesn’t understand how to motivate people. He seems to think you produce ambitious people by acting like a drill sergeant: Be tough. Impose rules. Offer carrots when they achieve and smash them with sticks when they fail.

But as Daniel Pink writes in his book Drive, these systems of extrinsic reward are effective motivational techniques only when the tasks in front of people are boring, routine, and technical. When creativity and initiative are required, the best way to motivate people is to help them find the thing they intrinsically love to do and then empower them to do that thing obsessively. Systems of extrinsic rewards don’t tend to arouse intrinsic motivations; they tend to smother them.

Don’t grind your kids until they become worker drones; help them become really good at leisure.

Today, when we hear the word leisure, we tend to think of relaxation. We live in an atmosphere of what the theologian Josef Pieper called “total work.” We define leisure as time spent not working. It’s the pause in our lives that helps us recharge so we can get back to what really matters—work.

But for many centuries, people thought about leisure in a very different way: We spend part of our lives in idleness, they believed, doing nothing. We spend part of our lives on amusements, enjoying small pleasures that divert us. We spend part of our lives on work, doing the unpleasant things we need to do to make a living. But then we spend part of our time on leisure.

Leisure, properly conceived, is a state of mind. It’s doing the things we love doing. For you it could be gardening, or writing, or coding, or learning. It’s driven by enthusiasm, wonder, enjoyment, natural interest—all the intrinsic motivators. When we say something is a labor of love, that’s leisure. When we see somebody in a flow state, that’s leisure. The word school comes from schole, which is Greek for “leisure.” School was supposed to be home to leisure, the most intense kind of human activity, the passionate and enjoyable pursuit of understanding.

The kind of nose-to-the-grindstone culture Ramaswamy endorses eviscerates leisure. It takes a lot of free time to discover that thing we really love to do. We usually stumble across it when we’re just fooling around, curious, during those moments when nobody is telling us what to do. The tiger-mom mentality sees free time as a waste of time—as “hanging out at the mall.”

A life of leisure requires a lot of autonomy. People are most engaged when they are leading their own learning journey. You can’t build a life of leisure when your mental energies are consumed by a thousand assignments and hoops to jump through.

A life of leisure also requires mental play. Sure, we use a valuable form of cognition when we’re solving problem sets or filling out HR forms. But many moments of creative breakthrough involve a looser form of cognition—those moments when you’re just following your intuition and making strange associations, when your mind is free enough to see things in new ways. Ninety-nine percent of our thinking is unconscious; leisure is the dance between conscious and unconscious processes.

The story Ramaswamy tells is of hungry immigrants and lazy natives. That story resonates. The vitality of America has been fueled by waves of immigration, and there are some signs that America is becoming less mobile, less dynamic. But upon reflection, I think he’s mostly wrong about how to fix American culture. And he’s definitely not getting invited to my next sleepover.