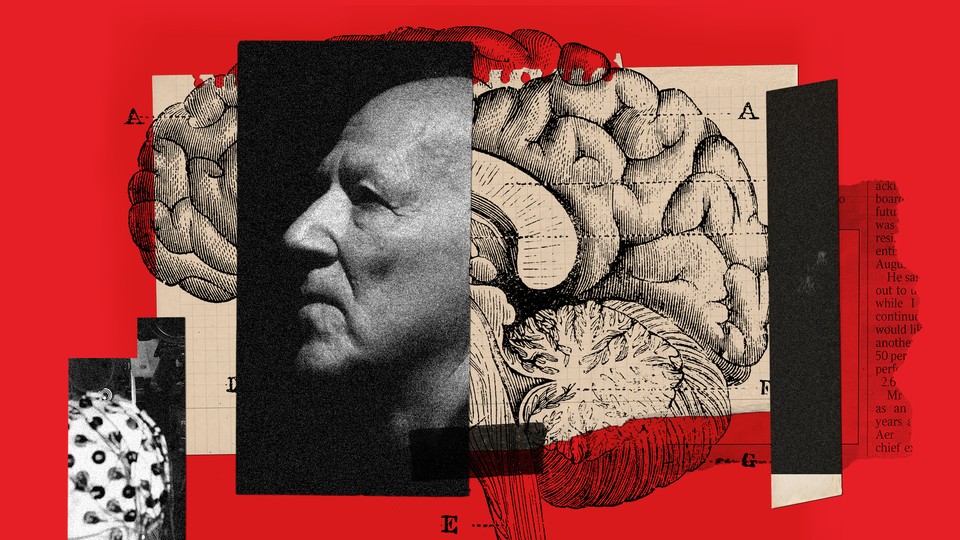

Inside the Human Brain—Or Werner Herzog’s, At Least

5 min read

Once, at the height of COVID, I dropped off a book at the home of Werner Herzog. I was an editor at the time and was trying to assign him a review, so I drove up to his gate in Laurel Canyon, and we had the briefest of masked conversations. Within 30 seconds, it turned strange. “Do you have a dog? A little dog?” he asked me, staring out at the hills of Los Angeles, apropos of nothing. He didn’t wait for an answer. “Then be careful of the coyotes,” Herzog said. “The coyotes will come and eat it. That’s what they do. They hunt for little dogs.”

I felt for a second as if I had entered a Herzog documentary, because this is what he does: allows himself to articulate the inner ping-pong. Many people might stand in the middle of a jungle thicket and have this kind of deep thought (as Herzog once did on camera): “We have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth and overwhelming lack of order.” But they would most likely keep it to themselves. Herzog’s sense of wonder seems to overspill any filter, whereas mine hides behind the curtain of shame most of us possess. And even if, now that he is in his 80s, this guilelessness has become a bit of a shtick (he has voiced self-serious versions of himself multiple times on The Simpsons), it is still his charm. It helps that his Teutonic timbre makes even his most obvious observations or glaring inanities sound somehow, weirdly, profound.

In his latest documentary, Theatre of Thought, Herzog applies himself to the mysteries of the human brain. The topic is more scientific and technical than most of his directorial targets, which tend to indulge his abiding interest in nature’s violent and irrational ways—grizzly bears and volcanoes, cave art and albino crocodiles. Just how uncomfortably geeky a match this is for the more intuitive Herzog becomes apparent less than 15 minutes in, as he is listening to Darío Gil, a head researcher at IBM, sketch out the details of quantum mechanics on a whiteboard. Herzog suddenly lowers the audio on Gil’s lecture and amplifies his own voice-over. “I admit that I literally understand nothing of this,” he says, “and I assume that most of you don’t either.”

If I can spoil things a bit: Herzog learns very little about the brain. Yes, he goes on an extensive tour of cutting-edge research, discovering that scientists are coming closer to reading our thoughts, that we may soon be able to control artificial limbs with our minds, that quantum computers might replicate the workings of the cerebral cortex. But the mystery of thought, of consciousness, remains a mystery. Herzog himself closes his film by embracing defeat, saying that he is now even “more mystified.”

This might sound like the exercise was a dud, except that we also spend almost two hours inside Herzog’s noggin, and it is a wild one. His questions and digressions, which leave the scientists staring dumbfounded at the camera in awkward silence (which he prolongs for our pleasure), do a much better job of illustrating the intricacies of the human mind than any MRI.

Consider this short, random sampling of Herzog’s interjections, following the earnest efforts of researchers to explain their pioneering work:

“Would you like to communicate with a hummingbird?”

“So you could somehow press a button and taste a schnitzel?”

“Could it be that we all live in some sort of constructed fantasy world?”

“If somebody were dying and they had this interface, could the person, right after dying, report back to you that there is heaven?”

“How stupid is Siri?”

“Is this building behind you for real?”

At first, these questions seemed almost like a stunt; the closest corollary that came to mind was Sacha Baron Cohen’s Ali G, asking ridiculous questions with a straight face and making comedy out of the interviewee’s struggle to answer. But the responses themselves didn’t hold much attention—though I will say that many of these scientists had a shocking openness to Herzog’s repeated insistence that we might all be living in a Matrix-like simulation. And Herzog was not setting up a joke. He was just letting his mind meander where it wanted.

Just over a minute into a conversation with Tom Gruber, a computer scientist who helped create Siri, Herzog’s attention is snagged on a TV in the background of the shot, which is playing a looping video of fish swimming in schools. “I got intrigued by the images on the screen behind him,” Herzog’s voice-over suddenly cuts in. And he’s off in a reverie, Gruber’s talking head replaced by shimmering clouds of fish swerving in unison. Herzog wonders out loud: “Do fish have souls? Do fish have dreams? Do they only dream this landscape? Do they think? Do they have thoughts at all? And if so, what are they thinking about? Is the same thought simultaneously in all of them?”

This is easy enough to giggle at. But the contrast between the quantifying impulses of the scientists and the gloriously squiggly lines emerging from Herzog’s brain is revealing. Herzog often refers to himself—including at the beginning of this documentary—as a poet, though he’s not particularly known for writing verse. What he seems to mean is that there is the realm of information, and then there is something deeper—a set of existential questions, a way of looking at the world and cutting right to good and evil, to the soul, to the nature of nature. I wouldn’t necessarily place more value on this poetic approach to the problem of being human than a scientific one, but set against Herzog’s musings, the scientists do end up seeming too clinical and mechanistic about what goes on in our heads. I know which approach I would prefer to discuss over schnitzel.

One researcher from UC Berkeley, Jack Gallant, shows Herzog how specific voxels—tiny spots on our cortex—correspond to different concepts. It is possible to decode the brain this way, identifying where these notions live. But when Gallant shows Herzog an example of one voxel’s contents, the result seems more Dada than data: the concepts “sheriff,” “goose,” “brown,” “robin,” and “purse” all exist in the same place. The question of what it means that these ideas are grouped together in the folds of our brain seems better answered by a poet. And Herzog comes to his own dismissive conclusion, one that’s easy to endorse: “Where our numbers and names and concepts are located can be mapped, but there is no map of our thoughts.”