The Georgia Voters Biden Really, Really Needs

18 min read

With 224 days to go before an election that national Democrats are casting as a matter of saving democracy, a 21-year-old canvasser named Kebo Stephens knocked on a scuffed apartment door in rural southwestern Georgia.

“Hello, ma’am?” he yelled.

“What do you want?” a woman snapped back.

“It’s about the voting?” he said.

The door was in the city of Albany, a mostly Black, mostly working-class Democratic stronghold of about 70,000 people in an otherwise Republican area, the kind of place where high turnout among Black voters had delivered the White House to Joe Biden in 2020 and the Senate to Democrats in 2021.

Now it was spring, still weeks away from Biden’s unsteady debate performance, and he was behind. Polls were showing Donald Trump not only leading by several points in Georgia but chipping away at Biden’s support among Black voters nationwide. After winning just 6 percent of the Black electorate in 2016 and 8 percent in 2020, Trump was polling at about 17 percent, a figure that some Democratic strategists were dismissing as an early blip and others were calling a “five-alarm fire.” If that 17 percent held, Trump would win the highest level of Black support of any Republican since Richard Nixon got about 30 percent in 1960, a margin that could return Trump to the White House.

Meanwhile, around Albany, the mood among Democratic voters was not one of urgency. No campaign signs were staked in yards. No Biden campaign offices had opened yet, and no caravan of organizers was rolling into town. Republicans controlled the Dougherty County election board. The county Democratic Party was just creaking to life after being all but defunct for years.

In a place long defined by Democratic solidarity, old loyalties were fraying, and not only because prices were high or Biden’s message wasn’t getting out. There were also signs of the sort of frustration, resentment, and burn-it-down nihilism that has defined Trumpism. Right-wing propaganda was seeping into the social-media feeds of young influencers, and even that of Kebo Stephens, for whom saving democracy was not exactly a calling but a decent-paying job that an aunt got him until he could make his fortune as a TikTok influencer with his own fashion line.

Lately, he’d started watching TikTok videos featuring a retired U.S. Army colonel named Douglas Macgregor, a regular on Tucker Carlson’s show and the Russian-government network RT. He’d heard the colonel say “I don’t think we’ll ever get to the 2024 election.” He’d heard him say “I think things are going to implode in Washington before then.” Stephens had heard enough that he wasn’t even sure whom he might vote for anymore, and now a woman was answering the door.

“Hey, ma’am,” Stephens said, doing his best to follow a script on an app developed by the New Georgia Project Action Fund, the progressive group that had hired him. “I’m Kebo, and we’re out talking to voters today. On a scale of one to 10, how important would you say the upcoming election is for you?”

“Five,” the woman said through the crack in the door.

“Okay, and what issues affect you most?” Stephens asked. “We have things like cost of living, health care, reproduction rights, climate change, Israel-Palestine—”

“Crime,” the woman answered. “I don’t really have time for this.”

She shut the door. Stephens kept going, marking the interaction as a successful face-to-face contact, data that would filter up to Atlanta, where it would count as progress toward turning out hundreds of thousands of Black and brown voters presumed to be Democrats.

Among the many questions hovering over the election, one is how much further the old certainties of American politics can break down amid the seductions of authoritarianism and social-media propaganda. Albany, Georgia, is a startling place for such a breakdown to happen.

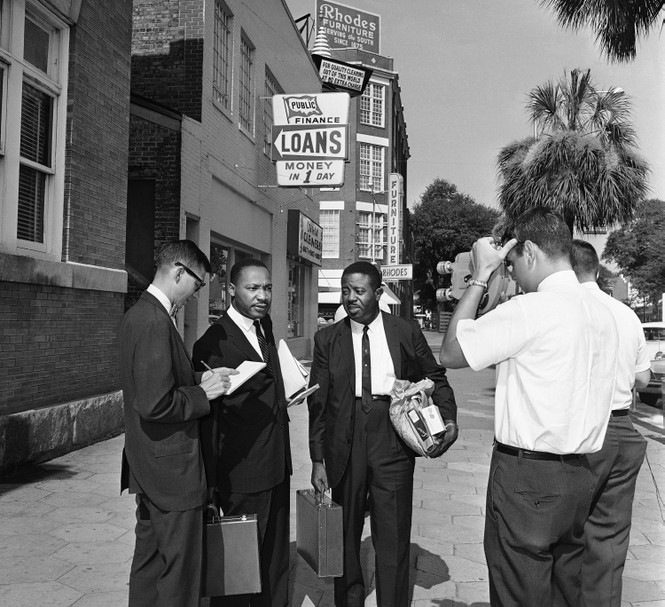

The city’s Black precincts have routinely delivered more than 90 percent of their vote to Democratic presidential candidates, a political solidarity rooted in brutal history going back to Albany’s earliest days as a commercial hub for cotton plantations. W. E. B. Du Bois described the city as a place where newly freed Black citizens stuck together “for self-protection” against the violent backlash after their post–Civil War enfranchisement. After the expulsion of Black state representatives during that period, Albany was the launching point for a protest march, a show of bravery that ended when white locals killed about a dozen participants in what is now called the Camilla massacre. The city became a battleground during the civil-rights era, when Martin Luther King Jr. led marches and Black citizens began voting as a bloc for a Democratic Party promising to advance the cause—all of which was history that Trump was trying to defy, and that Kebo Stephens had not yet learned, and now there were 217 days to go.

He and a colleague, Meacqura Sims, 23, headed out to their turf, driving through the Albany they knew. Neighborhoods of patched roofs and windows sealed with plastic. Worn-out apartment complexes owned by investors who kept jacking up rent. Blocks of payday lenders and dollar stores where Stephens noticed his food stamps buying less and less. Another shiny new car wash when the city already had more than 20. They turned into a subdivision and parked, then Stephens followed the sound of a hedge trimmer into a backyard.

“Excuse me!” he yelled to a man, who cut off the trimmer. “We’re seeing how people are feeling about voting. Do you vote?”

“We always vote,” said the man, and Stephens marked him down as a 10 on the enthusiasm scale.

He knocked on a blue door with a Welcome Home sign: “Fifteen,” declared the woman who answered, and he marked down the 15.

Sims rang a doorbell on a porch with a dead plant.

“Five,” said the woman who answered. “When I first started voting, it was a 10, but not anymore.”

“I hear that, but when we vote, we can make a real change,” Sims said, trying to follow a script that often felt wooden to her. “What issues are important to you today? Cost of living? Health care?”

“Health care definitely,” the woman said.

“Now that we’ve talked a little,” Sims read, “on a scale of one to 10, how important would you say voting is to you now?”

“I guess 10,” the woman said.

“I’m glad you feel a little more powerful,” Sims read, recording the 10.

A house with a broken-down, pollen-dusted truck in the yard: moved.

A house with falling-apart blinds: wrong address.

A house with a turned-over grill, creaking wood steps, and a crooked storm door braced with rusted paint cans: no answer.

A house with an Albany State University doormat: “I believe in voting,” said a woman, who credited Biden with getting her student loans forgiven. “That’ll be a 10.”

A few doors down: “I don’t trust neither side. Democrat or Republican.”

“Appreciate you, ma’am!” Stephens said. And on it went on a warm, sunny Tuesday when azaleas were blooming and anxiety was rising among Democratic strategists especially worried about the votes of young Black men like him.

Stephens himself was worried about so many disparate things he would not have known to worry about were it not for the viral TikTok videos that filled his phone every minute. He kept swiping through them.

He worried that the Baltimore bridge collapse was an inside job. He worried that World War III could begin at any moment. He worried a lot about his pineal gland, which he had learned was a part of the brain also called the “third eye.”

“It’s how we see our dreams,” he told me, heading to a door. “Like, when children first enter the world, it’s wide open. But it can become dull. Even school can dull the pineal gland. And as you grow up, it starts to close due to eating stuff.”

He rang a doorbell. Not home.

“Like fluoride,” he continued. “Like Red 40 dye that’s in stuff like hot chips. The FDA, they basically are not for the people.”

He crossed a green lawn to the next door. Not home.

He walked down the street, swiping to a video with more than 2 million views featuring Macgregor, whose voice drifted into the rural-Georgia afternoon.

“I think we’re going to end up in a situation where we find out the banks are closed for two or three weeks … I also think the levels of violence and criminality in our cities is so high that it’s going to spill over … I think Ukraine is going to lose, catastrophically … I also know that you get revolutionary change when people can’t eat. When they can’t afford to buy the food. When they can’t afford to buy the gasoline.”

At the next house, a woman was pulling into her driveway.

“I’m not interested,” she said through her window. “They’re not doing anything.”

“Yes, ma’am, I hear that a lot,” Stephens said, and asked for the one-to-10.

“Probably a one,” the woman said, offering that she always voted Democratic. “This year I don’t think I can do it. I thought if Trump runs again, I might vote for him.”

“It’s a lot of stuff that’s hard to understand,” Stephens said, and they went off script for a while, talking about gay marriage, toxic music lyrics, and immigrants who worked for local farms, factories, and chicken-processing plants.

“I’ve been seeing stuff where they are bringing people over to live basically for free,” Stephens said, referring to some video he’d seen.

“I’m not prejudiced, but they’re taking over,” the woman said, and then she was quiet, thinking about what she might do in November.

“I probably just won’t vote,” she said.

When the conversation ended, Stephens marked her down as “canvassed.”

And now there were 201 days to go.

At his rallies, Trump was saying that immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country,” and he was promising mass deportations. He was calling his political opponents “Marxists, Communists, and fascists” and vowing to use the presidency to prosecute them.

And far away from Albany, in the northwest corner of the state, Republican activists were already weeks into an aggressive effort that was one reason many Trump supporters were energized and optimistic about their prospects of winning Georgia and the entire election.

The strategy was being spearheaded by the group Turning Point USA, which had announced a $100 million campaign to zero in on so-called low-propensity voters, people who did not vote regularly but had been identified as likely pro-Trump based on factors such as possessing a gun license. The group had developed its own app, which geolocated the names, addresses, and phone numbers of those voters in targeted counties. Its website featured a huge clock ticking down the days until the election, and week after week, local GOP leaders were pushing the app out to their members and rallying around the idea that the nation would not survive another Biden presidency.

“We’re going into what could arguably be the last election in the U.S.A. as we know it this November,” the chair of the Paulding County GOP had told 40 people at a regular monthly meeting. “It’s time for us to do something.”

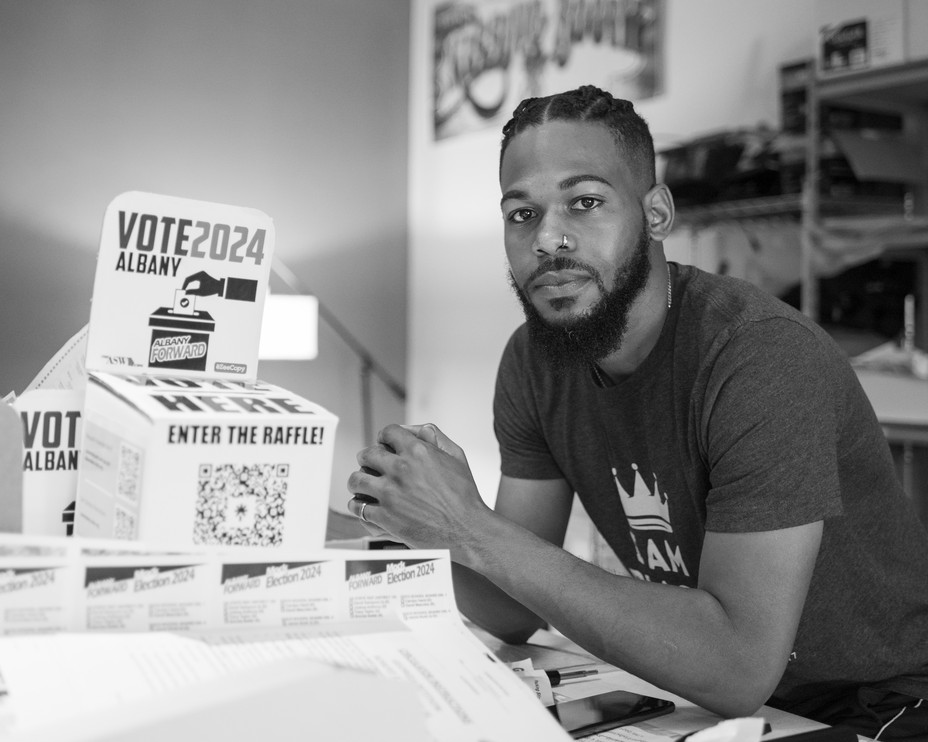

Meanwhile, the regular monthly meeting of the Dougherty County Democratic Committee convened at a public library in Albany. On a warm Thursday evening, 10 people attended. Since the county party relaunched in 2022 after a decade of infighting, mostly the same people always showed up—among them a teacher, an accountant, a former newspaper reporter, two retirees, and Demetrius Young, 53, a city commissioner worried that these well-meaning people did not fully grasp what could be coming.

He listened as the new chair recounted the success of a recent local candidate forum. She thanked the volunteers who had handled the sound system. She thanked the ones who had set out refreshments. Then she reported that the county’s GOP-controlled election board had denied an initial request to expand Sunday early-voting hours, when Black churches traditionally encourage members to go to the polls. Someone else mentioned that a neighboring county had instituted “pop-up” voting sites that were popping up in mostly Republican areas, and now Young raised his hand.

“We have to remember that we are dealing with election deniers, still,” he said, trying to inject some urgency into the room. “We are dealing with insurrectionists, still.”

He had grown up hearing firsthand accounts of the Albany Movement, the local campaign to challenge segregation that had ended with one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s biggest defeats. The local police chief had famously studied King’s tactics, then publicly embraced nonviolence to avoid bad press, even as he mapped out all the jails within a 60-mile radius and conducted mass arrests of protesters, including King, eventually negotiating King’s exit from the city with segregation intact. Young worried that a version of the same story was happening now. Democrats weren’t just struggling to turn out their base; they were also being outmaneuvered all over Georgia.

He reminded everyone that during the Senate runoff in 2021, a city commissioner had partnered with True the Vote, a conspiracist election-denier group, to challenge nearly 3,000 local voter registrations, and that a new state law had made such challenges easier. He reminded them that just down the road in Coffee County, Trump allies had allegedly breached voting equipment in an attempt to steal the election, helping to trigger the sprawling racketeering case that Trump’s team was successfully stalling in Atlanta.

He reminded them of what had happened at one polling place in October 2020, when he and other volunteers working with the group Black Voters Matter had been giving out bottles of water to people who’d been standing in line for six hours to vote, some of them fainting in the heat. A white woman had confronted Young, accusing him and the other volunteers of violating election rules. At one point she pulled out a gun and called them “dogs” and “Communists.” Later she claimed that she was “scared” because the group reminded her of the 1960s-era Black Panthers. State election officials found that the volunteers had broken no rules, and referred the woman to state prosecutors. But the more lasting impact was that another new election law was passed, this one forbidding volunteers from passing out water near polling places. Another reduced the number of drop boxes for absentee ballots. Gun laws had also changed; in 2022, Georgia became an open-carry state.

“So,” Young said as the meeting broke up, “the stakes are even higher than in 2020. It’s go time.”

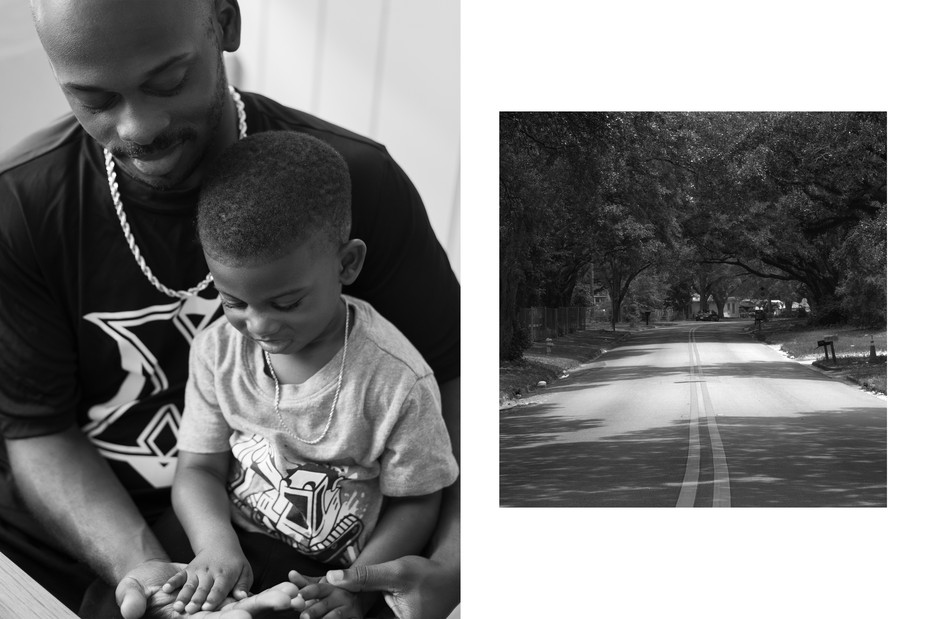

The next afternoon, he drove through his ward, on the south side of town, past old churches where King once spoke. He noted the falling-down house where his mother, Albany’s first Black female lawyer, had launched the lawsuit that integrated the city commission—the kind of case that has become more difficult to win in recent years as a conservative Supreme Court majority has dismantled the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

He glanced at the yards. Still no Biden signs. He stopped to see his aunt, Helen Young, who owns a barber shop in a rambling old house that had become the unofficial Democratic headquarters during the years the local party was fallow.

When Stacey Abrams launched her first campaign for governor, and her strategy to turn Georgia blue, in 2017, it was Helen Young who had taken the local campaign director under her wing. She put up volunteers in her house and shared a thick folder full of contacts across dozens of counties, from Albany south to Florida and west to Alabama. During the 2020 election, it was Helen Young who had relentlessly called Biden’s office for signs until finally his campaign sent an 18-wheeler full of them, which she distributed all over southwestern Georgia. When members of Black Voters Matter cranked up their operation, her nephew Demetrius had used his aunt’s contact list, mapping a route they drove in vans, playing music and handing out bags of collard greens to inspire people to vote.

“It was old-school,” he said now.

“I put balloons all up and down the street,” his aunt was saying.

That had been the mood in 2020, when Albany had suffered badly from the coronavirus, and the police killing of George Floyd had spawned protests all over the country. There was a sense of urgency.

Now the list was in some drawer. A TV was on inside the shop, and in the late afternoon Helen Young and her friend Tijuana Malone were half-listening to another sprawling CNN panel chewing over Biden’s prospects. Their own panel of two supported him, even if they did not feel the same enthusiasm as they did in 2020. They recalled Abrams’s second campaign, in 2022, when a strategist had set up an office on the third floor of a bank, which had struck them as a remote and unfriendly location that only some out-of-touch consultant would choose.

“They sent a strategist who didn’t know anything about here—a degreed professional,” Malone said. “I could feel the absence of us.”

“I had to have my own Abrams signs made up,” Young said. “And I feel I’m going to have to do the same thing for Biden this time.”

And now there were 198 days to go.

The Biden campaign announced that seven offices would be opening across Georgia. White House officials were emphasizing record-low unemployment and the strongest post-pandemic economy in the world, but in the craggy parking lot of a Piggly Wiggly, a shopper named Renee James was worrying about food prices. “What I don’t get here, I go to the Dollar Tree to get, but Dollar Tree is up. Now it’s Dollar Tree Plus.”

It was hot, and she put her one bag of groceries into her trunk.

“They’ve got a smaller area for $1.25 items, but it’s just potato chips and stuff like that. Oatmeal cookies were $1.50, and now they’re $3.50 or $4.50. Towels are $5, and they used to be $1.50. I’m just cutting back,” she said. “Like, I prefer wings, but today I got drumsticks because they were on sale. Me and my husband have about $200 a month for food, and if we run out, we just bring a couple of plates from my son’s.”

Regarding November, she said, “I’m still weighing that out.”

On CNN, an ever more sprawling nightly panel had shifted focus to the minutiae of Trump’s hush-money trial. A New York Times/Siena College poll would soon show Trump widening his lead in Georgia to 10 points. A prominent Democratic strategist, reluctant to openly criticize her party, was telling me privately, “I think the entire political landscape has shifted. I think we are in denial.”

And in another corner of Albany, with 195 days to go, a voter named Adam Inyang was telling me, “I think the Democratic Party has failed a lot of folks. Unfortunately, the GOP side isn’t the answer either. The answer is to exit and create a better system.”

He was 34, and had grown up in a Democratic household. He knew the local civil-rights history but was also part of a network of young Black men drifting away from all of that.

His shift began when his job running a print shop took him to the Washington, D.C., area, where he was opening a new store inside Reagan National Airport. He would see politicians and pundits traipsing to their gates, and sometimes he’d chat with them, and he began to think that what he saw on TV was a kind of performance. This was in 2014, the year when the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City, among others, sparked the Black Lives Matter movement. Inyang had joined the protests breaking out in D.C., at one point as part of a group aiming to shut down a highway, only that began to feel like a performance too. As he recalled it, the protest was more supervised than defiant.

“The police actually guided us onto the interstate,” he told me. “The police blocked the traffic for us. They started counting down because they only gave us so much time. I’m up on the median with my fist in the air. I got my photo taken and all. And I’m like, Okay, I’m seeing how all these parts are working together. You’re not making any change if the police are controlling your protest. I was like, We’ve got to stop this symbolism and find out what really brings change.”

He came back to Albany and ran for city commissioner on a platform of lowering utility rates and preventing crime. He lost, a result he blamed partly on old-guard Democrats, who he felt were afraid to support him. Then he began to think that maybe the old guard was part of the problem. Then, he said, “I went back to square one.”

For him, that was Huey P. Newton, the revolutionary founder of the Black Panther Party, whose lesser-known predecessor was established in rural Lowndes County, Alabama, in 1965 as a challenge to the local Democratic Party, at that time still controlled by white supremacists. Inyang had read about Newton in school. The idea of Black self-reliance appealed to him. So did the idea of third-party politics. Alternative news sources appealed to him too, especially an Indian journalist named Palki Sharma on a YouTube channel with 5 million subscribers, and the podcast of the conspiracy-minded British actor Russell Brand.

“Now that people can get real news as opposed to propaganda like CNN and Fox, people are able to say ‘We’re sending billions where? For what?’ That’s why folks are looking at RFK and Cornel West,” he said, naming third-party candidates he liked. “Those people are saying what matters to me. Stop the wars. Feed our kids here. Invest in business here.”

He wasn’t worried that voting third-party might help Trump win, or that Trump posed a threat to constitutional democracy.

“The whole Constitution can suck it,” he said. “That’s why we need a third party. That’s a trash piece of paper that protects a few people. It was not written for us. Tear that sucker up. Burn it. Start over. It does not represent the U.S. we actually live in.”

Inyang had his own YouTube show, which he streamed from the back of the print shop he now owns, and one of his favorite guests was another young Black influencer in town named King Randall, whom Inyang had known long before Randall accumulated nearly 300,000 social-media followers.

“On Instagram, you describe yourself as a Christian, a conservative,” Inyang had begun one interview with Randall last year. “Does that mean you’re Republican? Did you vote for Trump?”

Randall was wearing a Make Men Great Again sweatshirt, and a red Nike hat. “I’m not impressed by any president or politician,” he said. “But I would have preferred Donald Trump to Joe Biden.”

He, too, had grown up in a Democratic household. He had joined the Marine Corps, and returned to Albany at a time when gun violence was spiking, and decided that he needed to do something to help young men in his own neighborhood. He started tutoring. He started a summer camp where he taught boys handyman skills, which he called the X School for Boys. Then, in the summer of 2020, with protests raging after the police killing of George Floyd, he had tweeted out a video of the boys laying sheetrock, writing, “This is my way of fighting for black men while they’re alive.”

Within a few hours, the post went viral, and when he scrolled through the responses, nearly all were from white Trump supporters who lived outside Georgia. “This is beautiful!” read one. “This is wonderful!” read another. “How can I donate?”

His social-media following ballooned. He got a DM inviting him and his students to the Trump White House, and they flew to Washington for a tour. A wealthy Utah businessman flew them in a private jet to Salt Lake City, taking them tubing and skiing and giving them a gold American Express card for the duration of the visit. Randall attended the right-wing Conservative Political Action Conference. He began to think Tucker Carlson made sense when he blamed societal collapse on the emasculation of men, a claim that vaguely resonated with Randall’s religious upbringing, and his sense that the Democratic Party cared only about Black women.

“I think Black men want to get back to some sense of traditionalism,” he told me. “Matriarchy is not working for our community. Our young men are falling by the wayside. Nobody is asking Black men what they want. What they need.”

But now King Randall was getting what he needed. He had a steady stream of donors, 40 acres of land for a school he was building, a contact for Governor Brian Kemp, and a contact for Trump’s campaign. Recently, he’d met a staffer for Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

With 194 days to go, Kennedy was polling around 7 percent in Georgia, about the same percentage that Biden was trailing Trump by, whom Randall did not yet want to endorse and Inyang did not like—though both welcomed the chaos Trump had unleashed.

“I am so glad that Trump has fissured the world so much that now third parties are a much more strong, viable option than ever before,” Inyang said. “The Democratic Party? God rest their soul.”

And now it was June. Less than five months to go.