Stop Pretending You Know How This Will End

5 min read

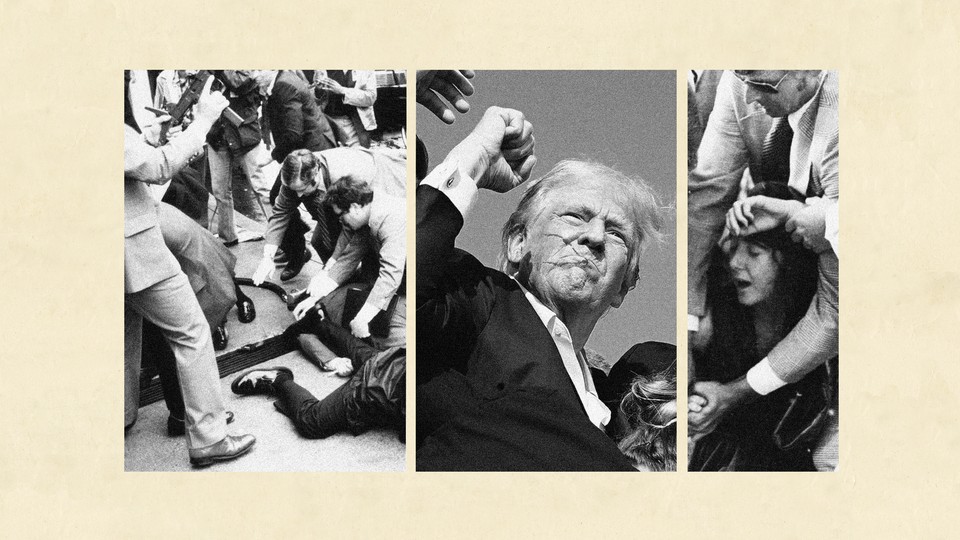

In the immediate aftermath of the failed attempt on Donald Trump’s life, pundits and politicians rushed to proclaim that they knew exactly how the awful event would affect American politics. Commentators on the left and right predicted on social media that “the election is over,” or that Trump was now fated to win in a landslide. “That’s the whole fucking election,” a Democratic House member told Semafor. A senior House Democrat told Axios on Sunday, “We’ve all resigned ourselves to a second Trump presidency.” Meanwhile, journalists foresaw an imminent escalation in violence and chaos. “We should all be terrified about what comes next,” Vox’s Zach Beauchamp wrote. On the front page of The New York Times, Peter Baker predicted that the assassination attempt was “likely to tear America further apart.”

Let me offer another interpretation of Saturday’s shocking event: Nobody knows anything. Anyone who claims to have already figured out precisely how Trump’s bloody ear will influence the 2024 election or strain the nation’s civic bonds is lying to you and to themselves. The history of failed assassination attempts in the United States and abroad offers only the murkiest indication of the path forward. “Would-be assassins are chaos agents more than agents that direct the course of history,” says Benjamin Jones, an economist at Northwestern University who has studied the effects of political assassination attempts over the past 150 years. These liminal figures—light-years from fame, yet inches from infamy—tend to change the world in minuscule ways, if they change anything at all.

The legacy of failed presidential assassination attempts in the U.S. should temper expectations that this past weekend was a world-historical event. Theodore Roosevelt was shot in 1912 campaigning for president in Milwaukee and, with Paul Bunyan heroism, continued his speech after being struck; he still lost. During a three-week span in 1975, two women tried and failed to shoot Gerald Ford. He lost his upcoming election, too. When Ronald Reagan was shot in 1981, a brief spike in his approval rating disappeared within a matter of months. It is hard to say that any of these failed attempts had a lasting effect on polls or politics in general.

True, none of those presidents campaigned during the age of social media, and none of the attempts on their lives produced an image as striking as that of a bloodied, defiant Trump pumping his fist to the crowd—an image that could “change America forever,” as one Washington Post writer put it. Perhaps American history really has been flung along some berserk causal pathway in the multiverse. But let’s give equal time to the possibility that nothing has changed at all. This presidential election is already unusual for how stable the race has been, even in the face of historic events on both sides, including the felony conviction of Donald Trump and widespread calls among Democratic elites for Joe Biden to drop out of the race. The electorate’s mind seems largely made up, given that Donald Trump has narrowly led Joe Biden for more than nine months.

The bloodied-Trump photo will surely thrill his supporters—but his supporters already supported him. In a more staid political environment, the incident might be expected to durably colonize voters’ attention, but it has already begun to be displaced by two new huge political stories—the dismissal of the stolen-documents case and the selection of J. D. Vance as Trump’s running mate—which will themselves be supplanted in due time. Within a month or two, the basic contours of the presidential election may well be the exact same as they were on Saturday morning, with Trump as a moderate but not overwhelming favorite to win his second term.

In a bygone age, historians and philosophers asserted that even successful assassinations were utterly inconsequential. The deaths of ancient rulers such as Philip of Macedon and Julius Caesar may have been dramatic, but the Hegelian and Marxist view of time saw history shaped by structural forces: class, economic growth, military development, geography. By comparison, a small knife, or a gust of wind that bends the trajectory of a bullet, was a trifle. After the death of Abraham Lincoln, the British politician Benjamin Disraeli put it bluntly: “Assassination has never changed the history of the world.”

This assumption flipped in the 20th century. Almost every chronicle of World War I treats the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand as its precipitating event. More recently, the killing of President Juvénal Habyarimana seems to have unleashed the Rwandan genocide, and historians including David Halberstam have argued that the assassination of John F. Kennedy prolonged the Vietnam War.

Successful assassinations are rare. In the 2009 paper “Hit or Miss? The Effect of Assassinations on Institutions and War,” Jones and his fellow economist Benjamin Olken amassed a data set of 298 assassination attempts on world leaders from 1875 to 2004; only 59 resulted in a leader’s death.

“When an authoritarian leader is killed, we see substantial moves toward democratization,” Jones told me. “But when that would-be assassin fails, the evidence is a mild move in the other direction, which is toward authoritarianism, even if the effect size is smaller.” When I asked how their research applied to the failed attempt to assassinate Trump, Olken stressed that failed assassinations led to a “tightening of the screws” only in authoritarian countries. “In democracies, we do not see that at all,” Olken said. “In our historical data, the United States is very much a democracy.”

The question before us today is whether and for how long that will remain true. Trump, a man who not long ago attempted to overturn the results of an election that he had decisively lost, is on the precipice of another four years as president of the United States, buoyed by a Supreme Court decision that expands the legal immunity of that office. “We’re in a time in the United States where there is more talk around authoritarianism and an increase in presidential power, along with explicit concerns around Trump’s plans in terms of being contained by checks and balances,” Jones said. “If you think of the U.S. as a democracy, you’d think this assassination attempt would have little effect on our institutions and politics. But if you think we’re edging toward authoritarianism, you might have this concern.” A successful assassination is a tragedy. A failed one is a test.