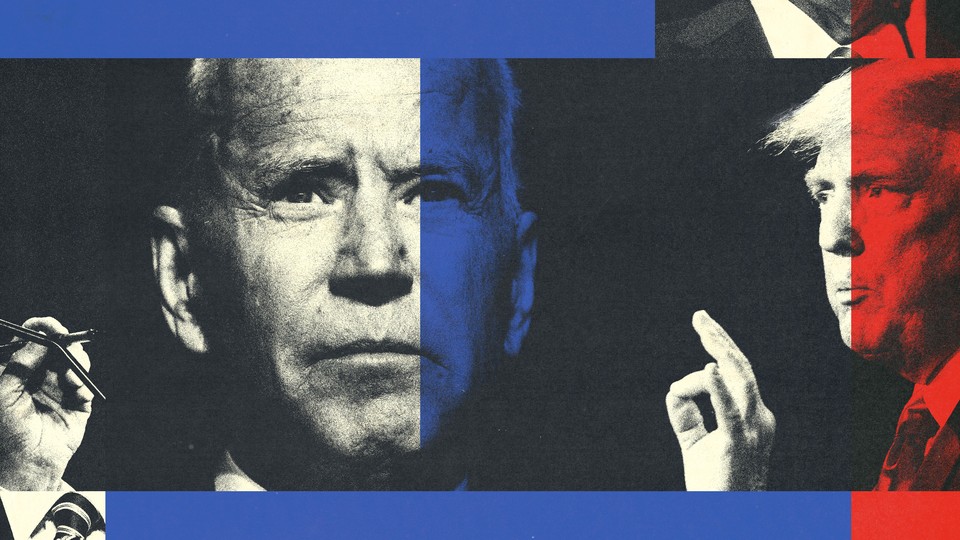

Biden’s Ever-Narrowing Path to Victory

11 min read

As Donald Trump prepares to accept his third consecutive Republican presidential nomination tonight, Democrats remain trapped in a stalemate that could ease his return to the White House.

The movement to force President Joe Biden to step aside has widespread support in the party, but probably not enough support to overcome his adamant refusal to do so. In turn, Biden’s position against Trump in polls is weak enough to leave the incumbent with long odds of winning a second term—but not such slim odds that they make the case for replacing Biden irrefutable.

Caught between the growing signs of danger for their candidate and the shrinking window to change course, Democrats are drifting toward November with widening divisions and a pervasive sense of dread. Republicans, meanwhile, are overflowing with confidence, as this week’s party convention has demonstrated. Many Democrats now fear that they face the worst possible situation: a weakened nominee who will not withdraw and is angrily feuding with donors, elected officials, and other former allies pressing for his removal.

Amid all of these concerns, the Biden campaign insists that he retains a path to victory, primarily through the three key Rust Belt battlegrounds: Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Some Democratic strategists and operatives with whom I’ve spoken since the debate agree. “Not only is the damage to Biden not as great as people are assuming, but Trump continues to be reviled,” Matt Morrison, the executive director of Working America, an AFL-CIO-affiliated group that politically mobilizes working-class people who don’t belong to unions. “That, somehow, has been overlooked in the past two weeks.”

But most Democratic political professionals—the party’s campaign managers, strategists, media consultants, and pollsters—are in a funereal mood about Biden’s chances to overtake Trump. Whit Ayres, a longtime Republican pollster who is critical of Trump, says out loud what most of these Democratic professionals will still say to reporters only under terms of anonymity. “If the Democrats persist in nominating Joe Biden,” Ayres told me this week, “they are essentially ceding the presidency to Donald Trump.”

By any measure, Trump is in a stronger position today than when he accepted his previous two presidential nominations. On the day Trump was first nominated, in July 2016, the national polling average maintained by the political website FiveThirtyEight showed him trailing the Democratic nominee, Hillary Rodham Clinton, by 2.5 percentage points. When President Trump accepted the GOP nomination again, in August 2020, that same average showed him trailing Biden by 8.4 percentage points.

Today, FiveThirtyEight shows Trump leading Biden by 2 percentage points. Yet that understates the extent of Trump’s advantage, as operatives in both parties agree. The main reason is Trump’s polling lead is greater than that margin in almost all of the swing states that will determine the election. The other reason is most of the other important measures in the polls are worse for Biden than his performance in the simple horse race against Trump. That indicates the difficulty Biden may face trying to expand his support enough to erase Trump’s lead.

Biden’s job-approval rating has been stuck at about 40 percent or less roughly since this time last year. Trump consistently leads Biden by double digits when voters are asked whom they trust more to handle the economy (with similar results for queries about immigration and crime). And in multiple polls, big majorities say they consider the nation on the wrong track, and believe that Biden’s agenda has left the country worse off.

These trends place Biden closer to the recent presidents who lost reelection than those who won a second term. The defeated incumbents include Jimmy Carter in 1980, George H. W. Bush in 1992, and Trump himself in 2020. Looking across that history, the longtime GOP pollster Bill McInturff said to me that “every conventional polling standard tells us Joe Biden is going to lose.”

Beyond these downbeat views of his record, Biden faces bleak assessments of his personal capacity. The most obvious problem is the consistent polling finding that a majority of voters believe he lacks the mental and physical ability to do the job now, let alone for another four years. But Biden is also struggling on other measures that derive from this central concern. In a CBS/YouGov poll released earlier this month, just 28 percent of voters described Biden as tough and only 18 percent called him energetic; for Trump, the comparable numbers were 65 percent in each case. And that survey was taken before Trump’s defiant response to being shot on Saturday.

That searing event may serve as the bookend to last month’s presidential debate in what has been a disastrous spell for Biden. The debate compounded existing concerns about Biden’s weakness, then the assassination attempt reinforced perceptions of Trump’s strength.

“You put a picture of Trump shaking his fist in the face of an assassin alongside a picture of Biden’s blank state in the debate, and there you have the choice,” Ayres told me. Trump’s critics in both parties fear that such a vivid contrast could validate Bill Clinton’s famous maxim that, in American politics, “strong and wrong” usually beats “weak and right.”

Against these headwinds, the Biden campaign maintains that it still can compete for all seven of the swing states across the Sun Belt and Rust Belt. But hardly any other professionals in either party believe that Biden can plausibly win Georgia or North Carolina in the Southeast; as for the southwestern battlegrounds of Arizona and Nevada, polls consistently show Trump leading there as well.

The dominant view among Democrats is that the most—perhaps the only—plausible path to stopping Trump runs through the industrial Midwest. If Biden sweeps Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, and holds every other state that he won in 2020 by 2.5 points or more, he would reach exactly the 270 Electoral College votes he needs to win. (That arithmetic would also require Democrats to hold the District of Columbia, as well as the congressional district centered on Omaha, Nebraska, in one of the two states that award some of their electoral votes by district.)

Jen O’Malley Dillon, the Biden-campaign chair, claimed in a recent memo to staff that the Sun Belt states are still within reach, but she did acknowledge that winning the big three Rust Belt states was “the clearest pathway” to victory. As O’Malley Dillon noted, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin are each part of what I termed in 2009 the “blue wall.” That referred to the 18 states that ultimately voted Democratic in all six presidential elections from 1992 through 2012.

Recent history offers Democrats some reasons for optimism about the Rust Belt battlegrounds. Trumpwon the 2016 election because he dislodged Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin from the blue wall by a combined 78,000 votes. But after Trump’s unexpected breakthrough then, resistance to him has powered a substantial Democratic recovery in all three states. In 2018, Democrats won the governorship of those states; in 2020, Biden won them all fairly comfortably; and in the 2022 midterms, the Democrats swept the three governorships again—in each instance, by wider margins than Biden’s victory two years earlier.

Biden’s position is relatively stronger in these three Rust Belt battlegrounds than in the four Sun Belt ones largely because of the surprising racial inversion shaping the two parties’ coalitions this year. Compared with 2020, Biden’s support has eroded considerably more among nonwhite than white voters and more among younger than older voters (trends that his campaign says have persisted after the debate in its own polling). That shift has left the president facing a tougher climb in the younger and more racially diverse Sun Belt states than in the older, less diverse industrial ones—a head-spinning reversal for strategists of both parties.

Reinforcing the Biden campaign’s imperative of focusing on the Rust Belt is the fact that the minority population there is concentrated among Black voters. Democrats believe they have a better chance of reversing Trump’s early inroads with this demographic group than with the Hispanic voters more plentiful in the southwestern states.

Biden usually runs better in Wisconsin than in any other swing state. As for Michigan, Adrian Hemond, a consultant for Democrats and progressive causes, told me, “You can’t feel great about it, but you certainly can’t feel like all is lost.” Of the three states, Biden is performing most poorly in the one with the most electoral votes: his original home state of Pennsylvania. But if Biden can’t sweep all three former blue-wall states, every other path forward for him is rocky.

The Biden campaign’s message to legions of distraught Democrats comes down to one word: wait. The core of its case for recovery is that Biden will revive when, in the final weeks of the election, voters fully weigh reelecting Trump.

“We know that the election for many voters is still not clearly defined as a choice between Biden and Trump,” Dan Kanninen, the Biden campaign’s battleground-states director, told me this week. “Once we do define that choice on the issues—on the record of Joe Biden, on values, on what Donald Trump represents—we move voters to our camp. We know the voters whom we have to win back favor us quite a bit more on all those fronts.”

Moreover, Kanninen said, Biden has spent months building a grassroots organization to deliver that message in the swing states, while Trump and the GOP are now scrambling to catch up (with a big financial assist from Elon Musk). “When those core issues are front and center for voters, with an apparatus in these states,” Kanninen told me, “and with trusted messengers that can drive that home to voters, that’s how you win.”

Biden advisers maintain that he is still well positioned because so many of the voters who have moved away from him since 2020 are from traditionally Democratic-leaning constituencies—particularly younger, Black, and Latino voters. “The people who are still making up their minds in this election—and there are enough of them in the key battleground states that the president can win—do not like Donald Trump,” Molly Murphy, one of Biden’s pollsters, told me. “They have deep concerns about him. Those double dislikers feel much more intensely negative toward Trump than toward the president. That is why this is not yet settled.”

Few outside Trump’s own campaign would dispute that resistance to the former president remains substantial, with most voters viewing him unfavorably, many considering him a threat to democracy, and crucial elements of his agenda and record—such as extending his 2017 tax cuts for the rich and corporations, and overturning Roe v. Wade—remaining unpopular.

Even so, many operatives in both parties consider it wishful thinking—“delusional,” Ayres said—to believe that Biden’s standing in the polls will inevitably rise as voters focus more on Trump. Strategists in both parties believe that the doubts about Biden’s capacity will prevent him from shifting voters’ attention solely to Trump.

If anything, the comparison between the two tends to benefit Trump: Retrospective assessments of his job performance now typically exceed his highest ratings during his actual presidency. That may be because voters are reconsidering Trump primarily on the issues that cause them the most discontent with the current president—inflation, the border, and crime—rather than on other aspects of Trump’s tenure they disliked at the time. Although Biden has virtually monopolized TV ad-buying across the swing states all year, a new survey released this week showed that Trump’s retrospective job approval was now at least 7 points higher than Biden’s current one in all of them. That is a formidable advantage.

Tresa Undem, a pollster for progressive groups and causes, points to a further flaw in the strategy of framing the race as a referendum on Trump: It requires Biden to drive home a cogent negative message—something that he has shown little consistent ability to do. “Biden’s problem is that polling for months and months shows that he has zero room for error just to have a shot at winning,” Undem told me. “That’s where the ability to campaign effectively becomes a real issue—articulating one’s record, one’s vision for the future, and the threat in clear, inspiring, and convincing ways. Is he up for that?”

Like many other worried Democrats, she fears the answer is no. That’s why Undem, along with the great majority of Democratic strategists and donors I’ve spoken with since the debate, desperately wants the party to replace Biden with another nominee, probably Vice President Kamala Harris. Yet no clear consensus to replace Biden has emerged among Democratic voters, elected officials, or interest groups.

The movement to replace Biden seems to wax and wane on an almost hourly basis. Yesterday, Representative Adam Schiff, who is running for a U.S. Senate seat in California, provided new momentum when he called on Biden to withdraw; late in the day, ABC’s Jonathan Karl reported that Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer had privately urged Biden to step aside in a meeting last weekend. But the president still appears dug in. And Biden’s allies are pushing forward with a plan to short-circuit opposition by holding an online roll-call vote of delegates to renominate him before the Democratic convention opens in Chicago on August 19—though yesterday they backed away from the accelerated timetable first proposed. More twists seem inevitable before Biden’s fate as leader is settled.

The implications of a Trump victory extend far beyond a second White House term. If a decisive Trump win in November also delivers an unassailable Senate majority, that could reshape American life and the underpinnings of our constitutional democracy long after 2028.

Democrats this year are defending three Senate seats in states Trump is virtually certain to win (West Virginia, Montana, and Ohio); five more seats in swing states where Biden now trails (Arizona, Nevada, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin); and several other seats in blue-leaning states where the presidential contest looks unexpectedly close (including New Mexico and New Jersey).

Democrats have been reassured by polls showing that their Senate candidates are ahead in almost all of those states (except for West Virginia and, intermittently, Montana). Far from clear, though, is whether Democrats can maintain those advantages if Biden loses badly: In 2016 and 2020, just one Senate candidate, out of 69 races, won in a state that favored the other party’s presidential candidate.

Concern is growing among Democrats that Republicans will show up in droves to support Trump after he was nearly assassinated last weekend, whereas Democratic-leaning younger and nonwhite voters may feel too dispirited by Biden’s struggles to do the same. Resistance to Trump did spur big turnout in Democratic constituencies for the 2018, 2020, and 2022 elections (defying predictions of a “red wave” in the latter case). But Undem speaks for many Democrats when she questions whether hostility toward Trump will sufficiently offset disillusionment with Biden. “I keep wondering: Will people vote 100 percent against someone and zero percent for someone?” she told me. “Maybe if the threat becomes big enough, but it seems pretty dang hard.”

If a turnout edge does develop for Republicans, many of the Democratic senators now leading in swing states where Biden is trailing could also fall short. The consequences of such a surge cannot be overstated. It could allow Republicans to establish a majority in the Senate that would prove insuperable for Democrats until at least 2030 (because very few Republican-held Senate seats will be vulnerable to Democrats in the cycles before then).

With Trump back in the White House, a sustained Senate majority would give the GOP more than enough time to nominate and confirm much younger replacements for Supreme Court Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, both of whom are in their mid-70s. That could lock in a conservative majority on the Court until as late as 2050.

These are among the very high stakes that Biden and Democratic leaders are gambling with as the president insists, despite his obvious vulnerability, that he remains the best hope of preventing a second Trump presidency. As for Trump, such a restoration, which seemed inconceivable in the days after the January 6 insurrection, moves a step closer tonight with his address to a jubilant Republican National Convention.