One Law for Corruption, Another for Immunity

8 min read

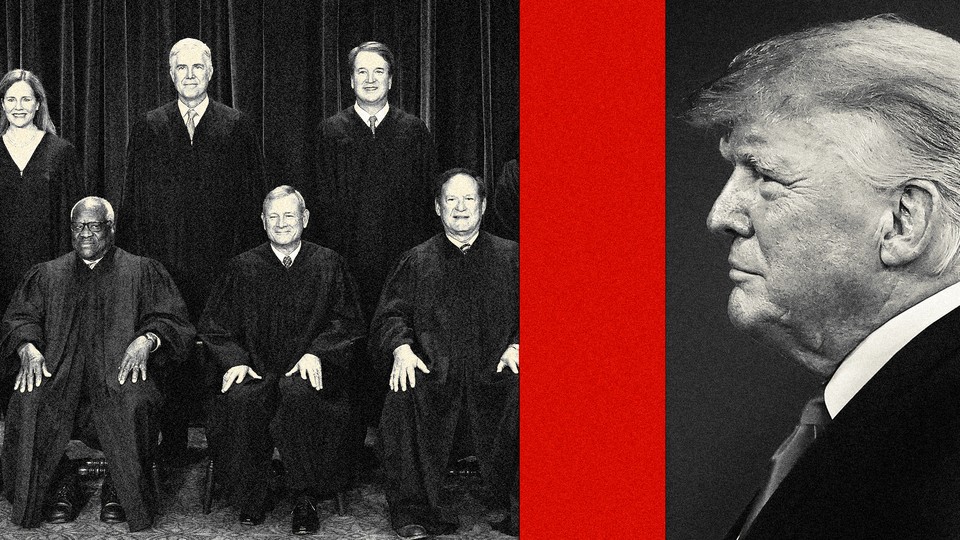

Democrats in Congress have been developing proposals for the reform of the Supreme Court for years—and this week, we learned that President Joe Biden is warming to the idea. Although a series of controversial cases recently decided by the Court has given new impetus to this movement, the need for an overhaul lies less in the rulings’ seeming rightward swing and more in the pretexts the justices have used to reach them. The Court’s reasoning is becoming more and more incoherent as the conservative majority tosses aside even its own recent jurisprudence in order to serve ideological dogma.

This month’s Supreme Court decision granting presidents at least presumptive immunity from criminal prosecution for much of what they do in office is a case in point.

It seems reasonable on its face: A democracy can hardly function if the Justice Department is free to prosecute a former president for executing policies that some successor happens to dislike. Read as an effort to ward off such a scenario, the concept is sound—but the details choke it. How is a prosecutor to distinguish “official from unofficial actions,” the opinion wonders, before offering guidance for answering that question.

To the dismay of Donald Trump’s critics as well as many historians and legal scholars, the Court staked out expansive boundaries for the “official” category. The ruling’s generosity runs entirely counter to a separate body of jurisprudence stemming from a series of cases on public corruption. There, the Court clearly defined what counts as an official act and what does not. The answer? Not much makes the grade.

If that precedent were respected, no item listed in the federal indictment of former President Trump for trying to reverse the outcome of the 2020 election would qualify as an official act. But the only way the Roberts Court could achieve its objective of erecting a shield around the nation’s chief executive was to contradict its own rationale for shielding a state’s chief executive.

Eight years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts signed the opinion in McDonnell v. United States,a decision that was stunning for its unanimity as much as for its content. It overturned the jury conviction, upheld on appeal, of a former Virginia governor for corruption. Governor Bob McDonnell had accepted some $175,000 worth of loans, cash handouts, and presents from Jonnie Williams, a businessman who dabbled in repurposing tobacco for supposedly benign products. In return for his money and bling, this would-be pharmaceutical executive wanted McDonnell to induce Virginia state universities to conduct clinical trials on a tobacco-based formula with a view to obtaining FDA approval. At the very least, Williams hoped that McDonnell could get the pills, which he claimed could treat inflammation, covered under the Virginia government employees’ health plan.

Proving bribery under U.S. laws, which have defined the act more and more narrowly over the past several decades, is not easy. You have to tie the briber’s gifts directly to something the public official does in return. Such an explicit quid pro quo transaction represents a tiny subset of the clever ways that well-heeled individuals and corporations make it worth an official’s while to further their interests.

Still, in the McDonnell case, prosecutors met the standard. They satisfied the jury that the quidand the quowere closely connected in the governor’s mind. For example, according to time stamps on emails, only minutes elapsed from when McDonnell checked with his benefactor about a promised $50,000 loan to when he asked his chief counsel to join him on devising strategies for clearing obstacles to the clinical trials Williams wanted.

Jurors and appellate-court judges had no doubt, in other words, that McDonnell had leveraged his position as governor to help Williams. But such help qualifies as part of a quid pro quounder the federal bribery statute only if the steps the officeholder takes to fulfill his side of the bargain are “official acts.” So, just like Trump v. United States, McDonnell hinged on which acts count as official.

Overturning two lower-court rulings, a unanimous Supreme Court decided in 2016 that none of the ways prosecutors showed McDonnell helping Williams counted as an official act. McDonnell’s activities deemed not to be official included: instructing his subordinates to meet with and listen favorably to Williams, having his staff organize a gala event at the governor’s mansion aimed at persuading state-university researchers to conduct clinical trials, and leaning on subordinates to make the decisions Williams wanted.

“To qualify as an ‘official act,’” Roberts spelled out, “the public official must make a decision or take an action on” a matter that “must involve a formal exercise of governmental power”—a lawsuit, for example, or a determination before an agency. Although “using [an] official position to exert pressure on another official to perform an ‘official act’” is an official act in its own right, “simply expressing support” does not equate to such pressure, according to this interpretation.

What are the implications of this McDonnell precedent for U.S. presidents?

The August 2023 indictment of Trump for conspiracy to defraud the United States (among other counts) includes a list of actions that the then-president and his alleged co-conspirators took to further their objectives. According to prosecutors, the president and his associates tried to “get state legislators and elections officials to subvert the legitimate election results,” and they discussed opening investigations with Justice Department officials and options for blocking certification proceedings with then–Vice President Mike Pence and members of Congress. To use Roberts’s own words, the co-defendants were “simply expressing support” for a course of action in calls and meetings with other officials. Under McDonnell,that activity is ordinary political practice and does not amount to deciding anything or even using governmental authority to pressure those officials to do anything.

The defendants also organized meetings of fraudulent state electors that, in the words of this month’s ruling, were allegedly “attempting to mimic the procedures” that real electors follow. But according to the McDonnell decision, “setting up a meeting” or “hosting an event” does not equate to “a formal exercise of governmental authority” or “qualify as an ‘official act.’”

Americans who believe that their president should be subject to the same laws as they are might reasonably take heart. Lower courts that are now charged with making specific determinations on each of Trump’s actions should be free to apply the same standards of official conduct that the Supreme Court laid out in McDonnell. The recent immunity ruling would still have the effect of stalling the January 6 case, but at least it would not serve as an invitation to Trump, if he is reelected, to behave even more egregiously in the future.

But that world of logical consistency is not the one that the Roberts Court has fashioned. Nothing in its recent history, or in the text of the Trump opinionitself, suggests that the majority has that much respect for its own prior work. Instead, Roberts has ignored, even contradicted, the precedent that he himself authored. In his guidance on how to tell official and unofficial acts apart, for example, he instructs lower courts not to “deem an action unofficial merely because it allegedly violates a generally applicable law.” That is, a decision or an order may be illegal, but it still enjoys presumptive immunity.

The exceptions to McDonnell continue. Trump, Roberts writes, met with “senior Justice Department and White House officials to discuss investigating purported election fraud.” Yet those discussions with subordinate officials are no longer considered informal chitchat, as they are under McDonnell: Even though no “decision or action” is taken on a matter resembling a determination before an agency, “Trump is absolutely immune from prosecution for the alleged conduct involving his discussions with Justice Department officials.”

As for discussions with Vice President Pence in which Trump expressed support for obstructing the congressional certification of the 2020 election, the former president enjoys “presumptive immunity.” The slightly weaker formulation is due only to Pence’s alternate role in that context as president of the Senate, answerable to another branch of government, rather than as a subordinate to the chief executive.

The same inconsistency applies to Trump’s interactions with state officials and private citizens. Under McDonnell, such conversations—none of which reached the level of a decision or a formal action—are unofficial. But again, the Roberts Court reverses its prior determination, saying that each exchange must be examined for potential connections to Trump’s constitutional duty to “take care that the laws are faithfully executed.” Even social-media posts and speeches to partisans favoring his second-term candidacy may, in this rendition, qualify as official acts.

Americans puzzled by these two contradictory Supreme Court rulings should take note of one striking consistency: whom the outcome favors. By defining the same plain words in opposite ways, each decision shelters a chief executive from legal review. McDonnell could not be convicted, because almost nothing he did as governor qualified as an official act; Trump’s prosecution could not move ahead, because Roberts’s guidance called almost everything the then-president did official, and therefore safe from scrutiny.

After the Supreme Court’s deeply unpopular Dobbsv. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision in 2022, which similarly disdained precedent by effectively repealing the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade, Roberts went on a campaign to shore up the Court’s flagging reputation. “The legitimacy of the Court,” he told a Colorado audience that year, “depends on the fact that it satisfies the requirements of the statute and the constitution, as John Marshall put it, to ‘say what the law is.’”

But justices are not licensed to say that the law is whatever they want it to be. They’re supposed to apply standards consistently. Apparently gripped by an ideological bent for protecting chief executives’ prerogatives—including to break the law—the Roberts Court dismantled that elementary rule of jurisprudence. So long as it keeps making things up this way, it will keep earning the contempt of the American people—not only for itself but also for the laws it is supposed to uphold.

Trump needed no pretext to despise U.S. laws and find ways to circumvent them. The Roberts Court’s legacy may include encouraging him, should he regain office, to refuse to relinquish his newly expanded power voluntarily. Is that what Roberts and his cohorts want?

If so, and if they’re willing to torture logic to get it, this danger—not the substance of any one decision—is the most urgent reason for reforming the Supreme Court.