Eight Books That Will Inspire You to Move Your Body

9 min read

This summer, in Paris, the Olympics will once again invite billions of people from around the world to watch some of the best athletes alive compete. Viewers tune in not necessarily out of love for the 20-kilometer race walk or the canoe slalom, but because of how sports are perfect metaphors for human drama. In the euphoria or devastation of the Games, our own struggles, both ordinary and existential, are made concrete: We see the possibility of transcendence, the basest instincts for treachery or cheating, the heartbreak of unrealized dreams, and the limits of human endurance. The athletes—and the spectators—belong to something larger than themselves.

Clearly, athleticism, exercise, and sports all lend themselves to heightened narrative stakes, and writers know this well. The thrills of competition, or of pushing one’s limits, don’t need to be Olympic-level to be compelling, however: In literature, amateurish endeavors and personal fitness can take on the same epic sweep as the events of the biggest games and leagues in the world. Authors frequently use the pursuit of athletic goals to reveal the complex, nuanced relationship that exists between the mind and the body.

These eight books—stories of swimmers, baseball players, and avid basketball fans—ask questions about what it means to approach and sometimes surpass limitations, and may inspire readers to pursue athletic goals of their own.

The Art of Fielding, by Chad Harbach

In American fiction, sports usually show up in one of two ways: Either they’re a figurative lens for understanding a main character, or the protagonist’s fortune depends on his success on the field. In Harbach’s novel, baseball does both. It serves as a symbol for a kind of sepia-toned American hopefulness and as a metaphor for the connection between a boy and his father. But the games in The Art of Fielding have very literal consequences. When Henry Skrimshander is recruited to play baseball for Westish College, a fictional liberal-arts school with a tenuous claim to Herman Melville, the sport becomes a path to a life outside his rural North Dakota town. As readers come to know the other players and coaches, the game turns into a microcosm of hope, ambition, and disappointment. In a narrative anchored by allusions to Melville’s work and a fictional classic baseball book, also titled The Art of Fielding, the players, coaches, and professors at Westish weather injuries, romantic entanglements, and questions that transcend baseball. One character muses, “He’d never found anything inside himself that was really good and pure, that wasn’t double-edged, that couldn’t just as easily become its opposite.”

Poverty Creek Journal, by Thomas Gardner

Gardner’s Poverty Creek Journal might appear, on the surface, to be something many compulsive endurance athletes know well: a straightforward record of a year’s training. But under that guise, this collection of lyric essays is a profound meditation on aging and grief, cut through with beautiful Annie Dillard–like observations of the landscape where the author runs. As the year goes on, the rituals of each morning’s training session reveal Gardner mourning after his brother’s unexpected death (“Cold rain this morning, 45 degrees, crying hard by the time I hit the pond,” he writes of one run). He threads the words of Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and Virginia Woolf through his reflections on the 2007 mass shooting at Virginia Tech, where he teaches, and he contemplates the tragedy’s devastating effect on the community. In contrast to the typical runner’s log, Gardner’s specifics of time and distance are only proxies for musings on the companionship of his training partners or, as middle age slows his pace, on the undeniability of his eventual death. Writing well about something as seemingly low-stakes as amateur distance training is hard. But in Gardner’s work, running only happens to be the means through which he observes the world, and his observations are those of a poet.

You Will Know Me, by Megan Abbott

The past decade has forced a public reckoning with the predatory culture of elite gymnastics, and Abbott’s 2016 thriller is deeply familiar with the decades of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse that so many athletes endured in top training programs. The immense pressure these institutions put on gymnasts—and their families—is central to the novel’s conceit. Told from the perspective of Katie, the mother of an aspiring Olympic gymnast named Devon, Abbott’s novel plays with the tension in how parental involvement can both protect children and harm them: The gymnasts’ parents, including Katie, live out their competitive fantasies and pursue vendettas through their kids. Then, when an unexplained death shocks the gymnastics world, it becomes clear that Katie—a woman who knows the intricacies of her daughter’s diet and workout routine, and the exact contours of her leotard-clad physique—does not know the secrets Devon has been keeping. That paradox makes plain how even when a child’s schedule is carefully controlled and their body fastidiously monitored, their internal life is ultimately their own.

Fit Nation: The Pains and Gains of America’s Exercise Obsession, by Natalia Mehlman Petrzela

Years into her career as a cultural historian, Petrzela, a New School history professor, turned her attention to the history of America’s obsession with fitness—in part because to outsiders, her passion for exercise seemed at odds with her academic life and interests. In chronicling the evolution in America’s attitude toward exercise from skepticism to an equation of fitness with moral superiority, Fit Nation brings the academic and athletic worlds together. The book touches on the history of the sports bra, Title IX’s impact on women’s participation in sports, the first running boom, the mania for aerobics and yoga classes of the past, and how current brands, such as Barry’s and Peloton, have become shorthand for an entire set of ethical, aesthetic, and financial positions. Exercise, Petrzela argues, is no longer just about bodily benefits; it’s also the manifestation of our collective, if fraught, belief that fitness represents virtue.

Endure, by Alex Hutchinson

For the purposes of Hutchinson’s book, endurance is defined by a researcher as “the struggle to continue against a mounting desire to stop.” For all the technological advances in the study of brain and sports science—the core-temperature-measuring pills used by Nike, the study participants pedaling to exhaustion—a great deal about the way the brain communicates with the rest of the body remains unclear. What’s also unclear is how humans can consistently reach the physical limits of their performance. Why, for instance, can the ultramarathoner Diane Van Deren summon the strength to break into a relative sprint near the end of a multiday trail-record attempt—especially when she must begin each morning by crawling until endorphins have numbed her pain enough that she can get on her feet? The book explores the distinct nature of discomfort and fatigue along with the relationship between anxiety and resilience, and asks if new (and contentious) techniques such as brain training might prepare athletes to persist in the late stages of competition. The questions Hutchinson poses about limitations are frequently specific to extreme endurance sports, but his book is also filled with instances in which ordinary people have managed seemingly impossible feats of endurance. Coupled with his stories of professionals who come up short, these anecdotes make clear that our quest to push onward is both universal and universally complex.

Spirit Run, by Noé Álvarez

Álvarez’s memoir of his participation in the 2004 Peace and Dignity Journey, a 6,000-mile endurance relay from Alaska to the Panama Canal, begins with a prologue of lyrical vignettes that introduce a handful of his fellow runners: a teenage mother whose baby died at seven weeks old, a Dené elder from Alaska, a young Bay Area man who emigrated from Mexico as a child. “And then,” Álvarez writes, “there’s me.” Álvarez’s own story begins with his childhood in the Yakima Valley of Washington, the son of Mexican agricultural workers, and then segues into a young adulthood marked by his search for spiritual and cultural belonging. Álvarez signs up for the Peace and Dignity Journey in hopes that the arduous work will open possibilities for connecting to Indigenous history, to his Purépecha grandfather’s culture, and to a larger community. He meditates on identity and home, but he also complicates the traditional quest narrative readers might be expecting: His willingness to write honestly about loneliness and doubt, and to acknowledge that a run—no matter how meaningful—cannot eradicate those emotions entirely, is welcome.

Basketball (And Other Things), by Shea Serrano, illustrated by Arturo Torres

Serrano’s illustrated history and reference book about basketball, and sometimes only tenuously related culture, is hilarious. It manages to be both specific enough (with pages of tables on Michael Jordan’s career statistics) and irreverent enough (it features a ranking of fictional characters who hoop including The Office’s Jim Halpert and Air Bud the dog) to appeal to a wide range of readers. Serrano poses hypothetical NBA death matches, speculates about who ought to be in the NBA-villain hall of fame, and ranks the greatest NBA conspiracy theories alongside the “three most interesting philosophical quandaries tangentially connected to a Carmelo Anthony cameo in a movie or TV show.” In the book’s introduction, written by the former NBA player Reggie Miller, Miller theorizes that basketball, more than football or baseball, has uniquely crossed over into daily American life. The sport is relatively accessible, and you don’t need a lot of gear or space. “Whether you played or just watched, we all grew up with it,” Miller argues. “Basketball is always there.” Even for those among us for whom the game was slightly less there—perhaps limited to 1990s starter jackets, High School Musical, or shouting “Kobe” when throwing trash into a bin—the book is delightful and moving.

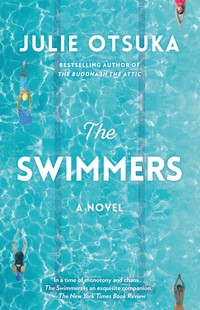

The Swimmers, by Julie Otsuka

Otsuka’s novel opens with brief, elliptical introductions to the dozens of men and women who swim at the subterranean pool on an unnamed university campus. “Most days, at the pool,” Otsuka writes in the first-person plural, “we are able to leave our troubles on land behind. Failed painters become elegant breaststrokers. Untenured professors slice, shark-like, through the water, with breathtaking speed … And for a brief interlude we are at home in the world.” Later, she moves to a second-person point of view, and readers come to more intimately know Alice, a swimmer with dementia who appears occasionally in the novel’s first section; through the eyes of her unnamed daughter, we grieve Alice’s decline and death, and we also mourn the fact that her child understands only vaguely what the pool meant to her mother. Although the specifics of the water and its swimmers are particular to Otsuka’s world, the notion of a place out of time—one where bodily repetition allows the bereaved, hopeful, disappointed, and imperfect among us to be relieved of the heartbreak of regular life—resonates far beyond the novel.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supportingThe Atlantic.