Evan Gershkovich’s Soviet-Era Show Trial

7 min read

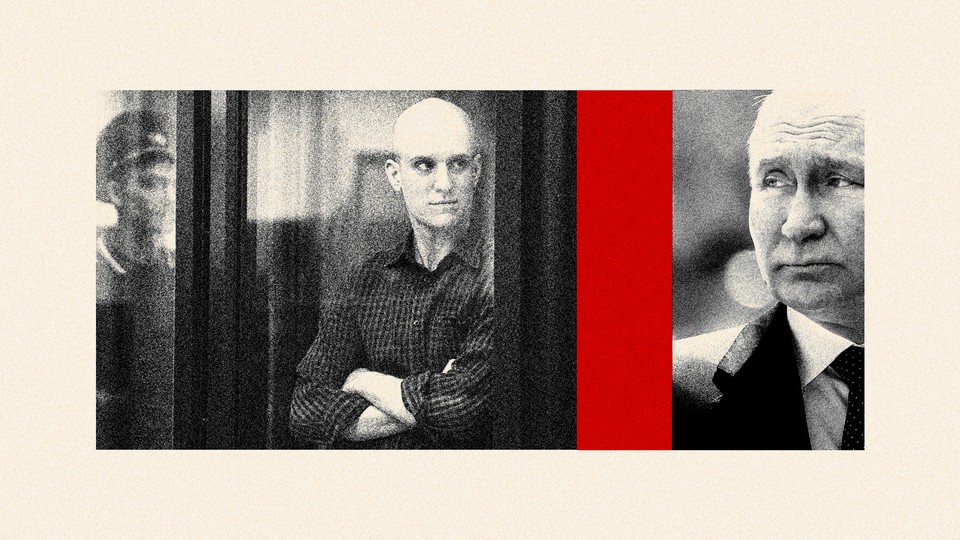

In video taken at his trial in Yekaterinburg in the Ural Mountains, the Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich looked older, gaunter, and grimmer than he did before his arrest last year. His head was shaved, and his eyes were flat and unsmiling. The change in his affect was hardly surprising: He had endured a year of questioning by Russia’s internal security agency, the FSB, and was facing almost two decades in prison.

Gershkovich’s case makes visible to Americans what those following human rights in Russia have already clocked: Russian prosecutions of political prisoners have become particularly brutal in the past couple of years, as the FSB has been reviving Soviet tactics of times gone by.

The security service has even invited public participation in these practices. Dmitry Muratov, the Nobel Peace Prize–winning newspaper editor, recalled on a recent podcast the means by which one inmate, an elderly woman, was denied the morale-boosting food parcels from loved ones that have long been allowed in Russian prisons: “I cannot get out of my mind the 20 packages of salt that some patriot with shiny eyes sent the woman,” he said. These were meant to take up her allotment for parcels. In Russia, “cruelty has become a synonym for patriotism.”

Gershkovich was first locked in the notorious Lefortovo prison in Moscow, where nobody ever meets with family. He was assigned an investigator, Aleksey Khizhnyak from the First Service of the FSB, who is well known for pressing espionage cases against both foreigners and Russians. Last month, Gershkovich, who has denied the spying allegations, was moved to the Ural Mountains for a secret trial. Last week he was sentenced to 16 years in prison.

Photographers and videographers were allowed to capture courtroom images of the Journal reporter for just 15 minutes, and journalists were told that he would not give interviews. So the world saw Gershkovich standing silently, with arms folded against his chest, observing his colleagues from a glass cage known as an aquarium. For months, the public had seen hauntingly similar images and videos of Alexei Navalny, as the Russian opposition leader seemed to waste away behind the dim, sepia glass of his cage.

Exhausted-looking defendants facing charges such as treason, espionage, extremism, discrediting the army, and terrorism have become a routine sight in Russia, paraded before cameras at Kafkaesque court hearings that turn on forced confessions. President Vladimir Putin has shown no sign of rebuilding the Gulag system that once entombed millions of Soviet political prisoners. But Tanya Lokshina, the associate director for Europe and Central Asia at Human Rights Watch, told me that today’s long sentences for political crimes, and the prosecutions of artists meant to coerce their silence, are ominously reminiscent of Soviet tactics.

So, too, is the use of duress to force confessions, another Moscow-based human-rights activist told me, speaking on condition of anonymity out of concern about reprisals. The NKVD in the Czarist era, then the KGB in the Soviet one, elicited these by humiliating, beating, and torturing prisoners, as well as separating parents from their children. Since the war began in Ukraine, says Sergei Davidis, who runs the Moscow-based NGO Political Prisoners Support, the FSB has revived the practice of coercing confessions.

Prison confessions are useful “for the most obviously fabricated cases against innocent people, in cases of terrorism, state treason, extremism, or espionage,” Davidis told me. “Prominent political prisoners don’t break, but dozens of arrested bloggers around the country admit their guilt, hoping to avoid long prison terms. The FSB, just like NKVD and KGB before them, need that for propaganda purposes, to prove their point where they have no evidence.”

Ivan Pavlov runs a team of Russian defense lawyers in exile that has worked on about a hundred espionage and state-treason cases. They call their group the First Service, echoing the name of the FSB department that handles state-treason cases. Pavlov told me that pressure to confess is not reserved for only activists and politicians: The FSB has turned the screws on “journalists, doctors, artists, scientists, pensioners, and even schoolchildren.” He worries that lawyers in political cases “advise clients to shut up, they advise them to bend to not make things worse,” he told me. “That is utterly wrong. Political prisoners are left alone, face-to-face with the most powerful secret police.”

Political Prisoner Support, Davidis’s group, counts 778 political prisoners in Russia, not including an estimated 7,000 Ukrainian civilians incarcerated in relation to the war. The United Nations calculates that Russia is holding more than 33 journalists behind bars. Appearing in an aquarium is a good indicator that a defendant is likely to do prison time, Davidis noted. A week before the Gershkovich trial, he told me, “There is no hope of acquittal for Gershkovich right now; of course he is going to be pronounced guilty.”

The targets of many current political trials are not even people accused, however falsely, of espionage, or of helping the West implement sanctions. They are independent thinkers, such as the playwright Svetlana Petriychuk and the director Yevgenia Berkovich, who produced a play about the exploitation of Russian women’s loneliness by Islamist radicals. Both ended up in glass cages, facing charges that their award-winning play justified terrorism.

As they awaited trial, Petriychuk wrote in a letter published by Rain TV, the authorities “put us in a cell with real murderers,” including a woman accused of cannibalism: “Somebody did not like a play, so they put a director and a playwright in such a cell.” On July 8, Berkovich and Petriychuk appeared handcuffed in court, where they were sentenced to six years in prison for “justifying terrorism” in their theatrical production. Neither accepted the charges.

Pavlov told me that many people facing such charges do hold out. “The FSB offered one of my clients, a 76-year-old professor named Viktor Kudriavtsev, leniency if he testified against one of his students. Kudriavtsev refused,” Pavlov said.

I spoke with some older Russian intellectuals who told me that Soviet repression under Leonid Brezhnev, or even Yuri Andropov, was mild compared with what dissidents now suffer under Putin. “We are dealing with street thugs in power,” Victor Shenderovich, a 65-year-old satirist, told me earlier this month. “The bandits know too well how to handcuff their victims to a pipe and make people suffer for a confession, or just for the fun of it. The Soviet regime was ugly, but nobody thought of killing the No. 1 political prisoner, Andrei Sakharov. Putin’s executors don’t blink.”

On February 27, another famous defendant, 70-year-old Oleg Orlov, appeared in handcuffs at a show trial in Moscow. Orlov, a co-chair of the Nobel Peace Prize–winning human-rights group Memorial, had documented the Kremlin’s abuses for more than three decades. A dozen muscle-bound security guards paraded him out of the courtroom to serve a two-and-a-half-year prison term for criticizing the army. He was not given a chance to say goodbye to his wife of 50 years.

Khizhnyak, the prosecutor in Gershkovich’s case, is well known for his coercive skills. Paul Whelan, the Canadian American citizen who was charged with espionage in Russia in 2018, was also assigned to Khizhnyak. Whelan petitioned for a change on the grounds that, as he told the court, “The Сaptain of the FSB Aleksey Khizhnyak humiliates my dignity and threatens my life.” His request was denied, and today Whelan is serving a 16-year sentence in a prison camp in Mordovia, where he is not allowed to receive mail or read books.

In 2019, Khizhnyak investigated an accusation of state treason against Antonina Zimina, the former head of a Baltic cultural center in Kaliningrad. She told prison observers that Khizhnyak directly informed her that he would never allow a doctor to see her.

Pavlov has known Khizhnyak for many years. “He is not a big man in size, in his 40s, not anybody you’d remember,” he said. FSB operatives, like the Gulag guards before them, are very often nondescript and mostly forgotten. But the names of the dissidents they torment enter into history.

Here is one: Ilya Yashin, a 41-year-old opposition leader and former Moscow city-council member, is serving an eight-and-a-half-year sentence for disseminating “fake news” about the Russian army in December 2022. In May, he was put in solitary confinement in a concrete box, called a “shizo” in Russian prison lingo, measuring 2 by 3 yards and reeking of sewage. The punishment was for 15 days, but as they reached a close, the guards added another 12.

In a court appearance on July 18, Yashin described his tiny cell as “kartser,” a word for isolation punishments in the Soviet gulag. Political prisoners are supposed to suffer, go crazy, freeze, and starve there, he said: “It’s not normal to torture people with smelly cells, hunger, and cold, and forbid them to see their relatives. There should not be methods once practiced by the NKVD and gestapo in our country, even if the president thinks that is an effective method.”

The court ruled that Yashin should be moved—to PKT, or “cell-type confinement,” a mere half step less punitive than shizo, for an indefinite time.