Five Books That Changed Readers’ Minds

6 min read

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Welcome back to The Daily’s Sunday culture edition.

When selecting a new book, it can be comforting to return to what’s familiar: the genres you know you love, the authors whose perspectives you share. But sometimes, the best books are the ones that challenge rather than confirm your expectations. For any reader looking to try something different, The Atlantic’s writers and editors answer the question: What is a book that changed your mind?

Siddhartha, by Hermann Hesse

The most memorable reading moments of my life came from a period of deep change: high school. Although I loved moody English-class staples such as TheCatcher in the Rye,A Separate Peace, and The Great Gatsby, the book that really cracked my brain open was Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. I can still see myself dog-earing and underlining the royal-blue, 160-page paperback during the summer between eighth and ninth grade. I was raised Catholic, and to the credit of my Jesuit high school, Siddhartha was required reading for all incoming freshmen. The 1922 German novel, which follows the titular character’s search for meaning, offered a glimpse into Eastern religions and could not have been further from the constraints of the Catholic Church. Thanks to the book, at age 14, I developed a genuine curiosity about the other side of the world—and above all, I learned that there was a form of spirituality available to me that didn’t require going to a physical church.

— John Hendrickson, staff writer

Panther,by Brecht Evens

Panther, by the Belgian cartoonist Brecht Evens, could be mistaken at first glance for a children’s picture book. Its early sections are appropriately whimsical: After her cat dies, Christine, a young girl who lives with her father, is visited by a talking panther. A charming, ever-morphing creature who explodes her world into color and calibrates himself carefully according to her needs, he is the consummate imaginary friend—and if the reader sometimes senses that he is something else, something wrong, they do their best to quash their unease.

I picked up Panther on a whim during the early pandemic—I liked the look of the sinuous, candy-hued panther on the cover, and I wanted something easy and adorable. So much for that: Panther was one of the most harrowing reading experiences of my adult life, a claustrophobic, slow-unspooling nightmare that jolted me out of my malaise. It challenged my conception of the medium’s boundaries, and punctured my belief in my ability to protect myself and others. Even now, thinking about it, I can feel the bile rise in my throat.

— Rina Li, copy editor

All Over but the Shoutin’, by Rick Bragg

Like John, I’ve sourced my pick from my high-school English class. Before I read All Over but the Shoutin’, a memoir by the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Rick Bragg, I didn’t care much for nonfiction writing—most of my exposure to the genre consisted of dense, stuffy textbooks and dry biographies of dead world leaders. But I’ll never forget the unfamiliar mix of emotions that seized me when I read the first page of the book’s prologue: “I used to stand amazed and watch the redbirds fight. They would flash and flutter like scraps of burning rags through a sky unbelievably blue, swirling, soaring, plummeting.”

Bragg writes about growing up poor in northeastern Alabama, the son of a woman who picked cotton and cleaned homes to give her kids a future, and a man who couldn’t step out from under the shadow of war. He introduced me to the art of creative nonfiction, challenging my early belief that lyricism could be found only in novels. This revelation set me on my current career path: Every time I read a story with sentences that sing like his, I return to that feeling of discovery.

— Stephanie Bai, associate editor

The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century, by Michael Denning

“What does it mean to labor a culture?” Michael Denning’s study of Depression-era working-class culture examines a diverse coalition of American artists, unionists, and intellectuals who toiled to answer this question after the economic upheaval of 1929. Though not its generation’s political victor, this “Popular Front” alliance communicated a lasting vision of anti-fascist social democracy using the forms of a newly minted culture machine: radio, Hollywood films, recorded sound.

Denning’s decision to decenter the role of the Communist Party distinguished The Cultural Front from other histories of Popular Front culture; his narrative makes room for those who left the party (or never claimed allegiance to it at all) but held on to a vision of political solidarity in their work. Among the more prominent figures he traces is the novelist Richard Wright. (Eighty years ago, The Atlantic published two essays by Wright—excerpts from his posthumous memoir—describing his break with institutional communism.) Wright depicted drivers, postal workers, and hotel janitors struggling to earn a living wage. “It is not Wright’s pessimism that is most striking,” Denning writes, “but his promise of community.”

— Sam Fentress, associate editor

Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, by Tom Holland

My mother was a Reform Jew. My father grew up Southern Baptist but later became not so much an atheist as a virulent anti-theist. So, depending on which parent had my ear that day, I was raised to believe that Christianity as an ideology fit somewhere on the spectrum between “silly and wrong” and “literally the worst thing ever.” Tom Holland’s Dominion, a book about Christianity and its influence, changed my mind in several ways. First, Holland persuasively argues that the tenets of Christianity—and its emphasis on universal rights for the poor and downtrodden—were revolutionary for its time. Second, he showed me that even secular Western modernity is suffused with Christian concepts, and that ideas as opposite as “wokeness” and fundamentalism draw water from the same tributary of thought.

— Derek Thompson, staff writer

Here are three Sunday reads from The Atlantic:

- The warehouse worker who became a philosopher

- Cape Cod offers a harbinger of America’s economic future.

- Kamala Harris defines herself—but not too much.

The Week Ahead

- AfrAId, a horror film about an AI digital assistant that starts to get too involved in a family’s life (in theaters Friday)

- Season 4 of Only Murders in the Building, a comedy-mystery series about a trio of amateur podcasters who investigate murders (premieres Tuesday on Hulu)

- My Child, the Algorithm, about the writer Hannah Silva’s conversations with an AI chatbot about love, dating, and parenting (out Tuesday)

Essay

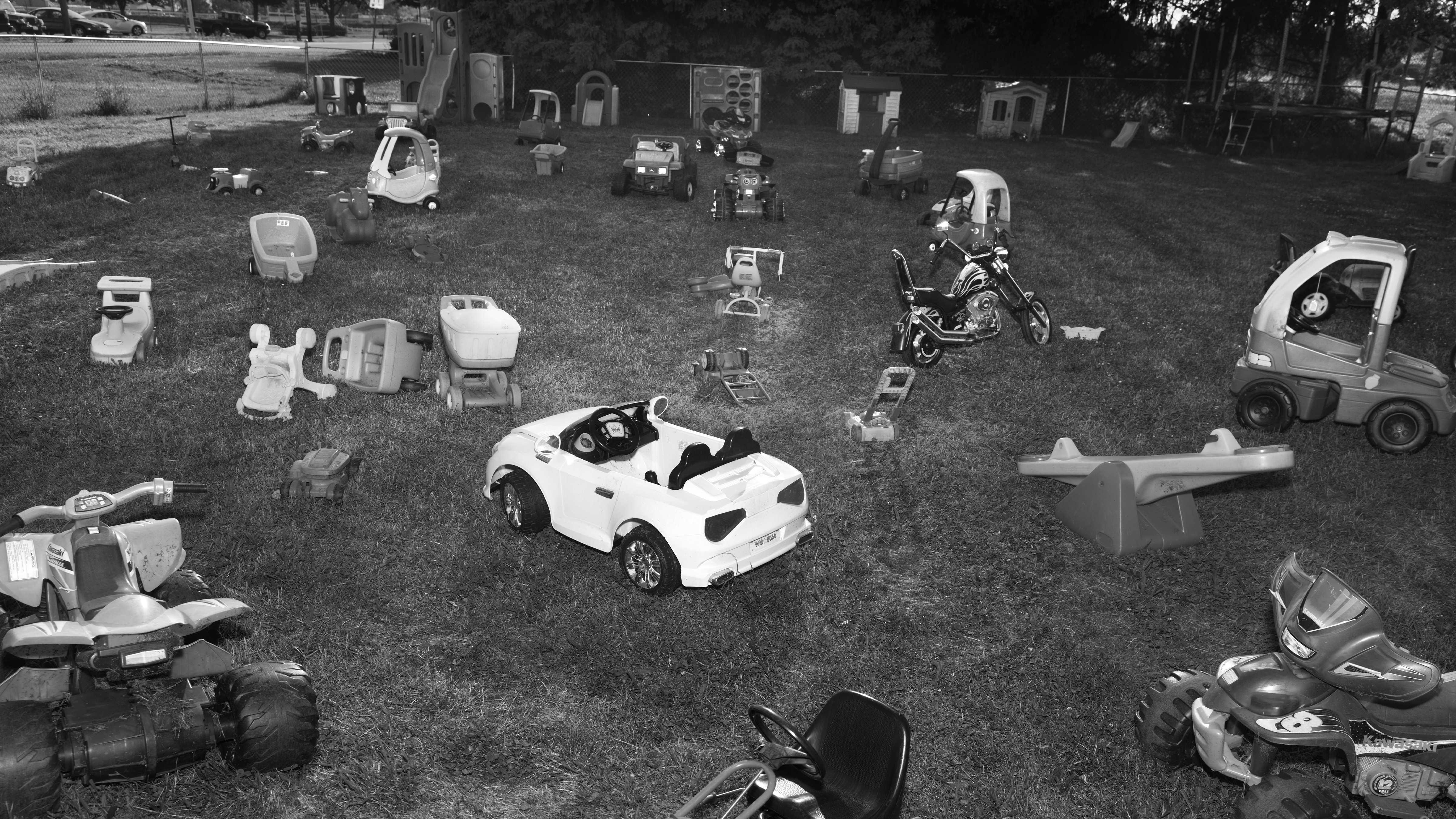

How to Solve the Summer-Child-Care Nightmare

By Elliot Haspel

To all the frantic parents who’ve survived yet another year of the summer-child-care shuffle: I salute you.

It’s a well-established fact that in the United States, finding summer child care can be hell. In a nation with lengthy breaks from school—and no guaranteed paid time off from work for adults—parents are left largely on their own to cobble together camps and other, frequently expensive, arrangements …

Solving this problem isn’t so complicated; it’s not like, well, trying to coordinate camp schedules.

Read the full article.

More in Culture

- A horror movie about befriending the rich and powerful

- What Gena Rowlands knew about marriage

- A bloodier, more mediocre The Crow

- Emily in Paris doesn’t need a makeover.

- Someone is watching. Is it God, or your boss?

Catch Up on The Atlantic

- Trump and the cocaine owl

- The asterisk on Kamala Harris’s poll numbers

- Tim Walz’s understudy could get a history-making promotion.

Photo Album

Check out these photos showing the residents of Iceland’s Westman Islands on patrol to find and rescue misdirected young puffins.

Explore all of our newsletters.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.