Start With a Lie

25 min read

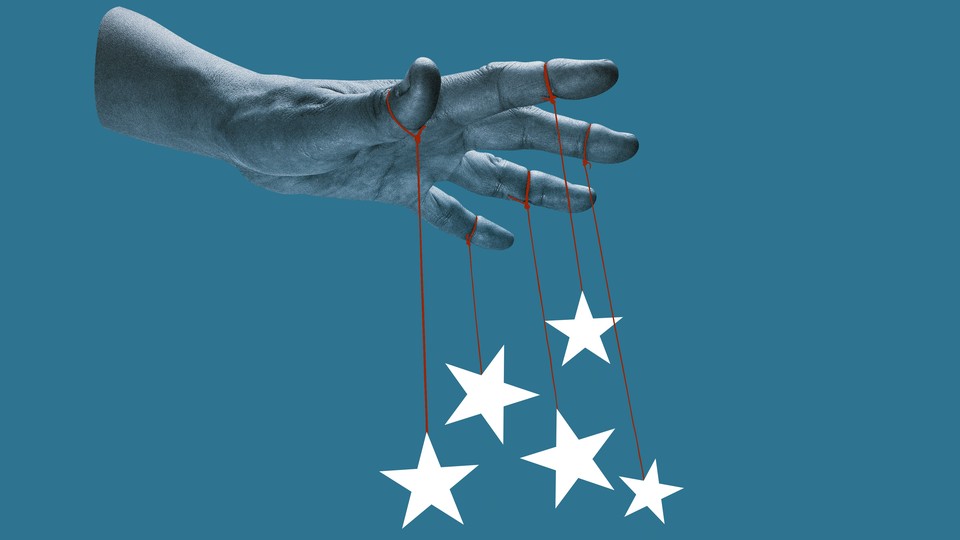

The corruption of democracy begins with the corruption of thought—and with the deliberate undermining of reality. Stephen Richer, an election official in Arizona, and Adam Kinzinger, a former Republican congressman, learned firsthand how easily false stories and conspiracy theories could disorient their colleagues. They talk with hosts Anne Applebaum and Peter Pomerantsev about how conformism and fear made it impossible to do their jobs.

This is the first episode of Autocracy in America, a new five-part series about authoritarian tactics already at work in the United States and where to look for them.

Listen and subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Pocket Casts

The following is a transcript of the episode:

[Music]

Anne Applebaum: Peter, picture this: A harsh winter has finally come to an end. Exhausted and ragged, America’s Revolutionary Army soldiers are huddled in tents. It’s Valley Forge. It’s 1778. And on a makeshift stage, a group of George Washington’s officers are putting on a play. It’s called Cato, A Tragedy.

Peter Pomerantsev: So they put on togas in the middle of a war?

Applebaum: History does not record what costumes they wore nor why, exactly, they were putting on a play at that particular moment. We do know it was one of Washington’s favorite plays. It was very popular in colonial America. It tells the story of the end of the Roman Republic, a democracy in its time, which was destroyed by a dictator, Julius Caesar.

Pomerantsev: So basically, Washington and the founders, you know—their vision of the end of democracy was to be a dictator taking the capital by storm and grabbing power.

Applebaum: Every generation has a vision of how democracy dies, and this was theirs.

Pomerantsev: I mean, today when I’m in America, I hear a lot of, like, references to: The Nazis are coming. The fascists are coming.

Applebaum: You and I have both lived in countries that became more autocratic over time, meaning that the leader or the ruling party usurped more and more power, eliminating checks and balances. And we both know that this doesn’t necessarily look like stormtroopers marching in the streets.

Pomerantsev: And it happens sort of slowly, almost imperceptibly, like mold eating away a building. And it’s like these little things that actually show you that you’re going in the wrong direction.

Applebaum: Things become even more dangerous when people are sick of the political conversation and just want it to end, and they want someone to come along and end it.

[Music]

Applebaum: I’m Anne Applebaum, a staff writer at The Atlantic.

Pomerantsev: I’m Peter Pomerantsev, a senior fellow at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University.

Applebaum: This is Autocracy in America.

Pomerantsev: In this podcast, we are not talking about some distant, dystopian, totalitarian state.

Applebaum: This is not a show about America’s future. It’s about the present.

Pomerantsev: There are authoritarian tactics already at work in America, eating away at the guardrails that prevent a leader from usurping power, and we are going to show you where.

Applebaum: Look at what we have already: widening apathy, politicized investigations, the embrace of the strongman cult.

Pomerantsev: And in this episode: psychological corruption.

Applebaum: Peter, when did you start to see things in the United States shift—shift away from a democratic culture?

Pomerantsev: Look, it’s a slightly personal issue for me. My parents were Soviet dissidents in Soviet Ukraine, where I was born. They were arrested by the KGB. We were exiled in the late 1970s (I was still a baby at the time), and after the fall of the U.S.S.R., I went and lived in Russia and Moscow from 2001 to 2010. That was the first 10 years of the Putin era and, in that time, I saw Russia degrade from a really rotten democracy to a really aggressive dictatorship.

And I actually remember one moment quite clearly: This must have been still during the Obama era. I was visiting the U.S. on holiday or for a work trip or something, and I suddenly found myself among groups of people who subscribed to this idea of birtherism, that Obama had not been born in America.

Applebaum: Exactly. And if he wasn’t born in America, then he’s not qualified to be president.

Pomerantsev: But it was the way they were talking about it. I mean, the evidence was not important to them. I mean, you could provide loads of evidence that Obama had been born in America—that wasn’t the point. The way they were using this conspiracy was kind of a real warning sign.

This wasn’t like, I don’t know, the Kennedy assassination, where people try to find the truth out. Here, people I met who signed up to the birther conspiracy didn’t care about evidence. They said things I heard in Russia when it was fading into dictatorship. They would say, I don’t know. The truth is unknowable. There are no such things as real facts or even evidence. But what did matter was how you signaled your political affiliation by making a conspiratorial statement.

Applebaum: Yep, and this is exactly how a conspiracy theory—a big lie—functions in an autocratic political system. It helps the leader, the autocrat, establish who’s loyal, who’s on our side, and who’s not. You know, if you promise to believe in the made-up story, then you can work for the government or the party or whatever, and if you don’t, you’re out. And so this then, not merit or hard work, determines who gets promoted and who runs things.

Pomerantsev: To show that you belonged to the Putin system, you had to repeat absurd lies that people Putin was arresting were guilty of totally absurd charges. You had to agree that Nazis were taking over Ukraine. You know, that could be socially very awkward at first, and people could get quite aggressive, especially when they were drunk. And after a while, it just became dangerous because if you disagreed with these absurd statements, with these conspiracy theories, then you were essentially an enemy of the state. And that would become incredibly dangerous.

Applebaum: When I first saw birtherism unfolding in the U.S., my first reaction was, No way is this happening here. Americans can’t fall for this kind of garbage.

Pomerantsev: Sorry—why did you think Americans were immune, just out of interest?

Applebaum: Wrongly, I imagined our political system is too big, and our democracy is too well anchored, and people don’t believe in conspiracy theories. And obviously I was wrong.

Pomerantsev: You know, once you get into this world where truth is a subset of power, it basically means that you can’t have democratic debate anymore.

[Music]

Applebaum: Eastern Europeans are familiar with the idea of ruling by conspiracy. But in contemporary America, this is new. And it’s so new, in fact, that I’m not sure Americans realize the significance of it.

Stephen Richer: In May of 2021, Donald Trump accused me of deleting files from the 2020 election. And that was—it’s just hard to describe, but it’s a little bit like the Eye of Sauron. With that, when it’s turned on you, you feel it, and people start contacting you, and you get a lot of ugliness directed your way.

Applebaum: Stephen Richer is an election official in Maricopa County, Arizona. And this disorienting accusation began, at first, as something completely impossible for him to imagine: that the president knew his name and was releasing statements directed at his office.

CNN newscaster Erin Burnett: Tonight, a bitter feud erupting among Arizona Republicans over an election audit of the state’s most populous county.

Fox 10 Phoenix newscaster Ty Brennan: Trump released a statement yesterday saying, quote, “The entire database of Maricopa County in Arizona has been deleted. This is illegal, and the Arizona state Senate, who is leading the forensic audit, is up in arms.”

Applebaum: At first, it felt somewhat impossible for Richer to take this kind of accusation seriously. He knew it wasn’t true. He could see all the files on the county computers every day he went to work. They hadn’t disappeared at all.

Brennan: In response, Republican recorder Stephen Richer sent out a tweet saying, quote, “Wow. This is unhinged. I’m literally looking at our voter registration database on my other screen. Right now. We can’t indulge these insane lies any longer.”

Applebaum: And then these claims started to take hold with other big players in the Trump circle.

Richer: Christina Bobb from One America News Network was here. The “Stop the Steal” candidates throughout the country would come into Arizona and almost pay pilgrimage, pay homage to that production.

Applebaum: And were the attacks on you—what were they accusing you of doing?

Richer: Everything from rigging tabulation equipment to falsifying evidence to deleting electronic files to, you know, turning my back on my people to not maintaining proper chain of custody. I just—the breadth is really breathtaking. Some of it is quite imaginative, and never in a million years would I have thought that somebody would have accused me of shredding ballots from the 2020 election, feeding them to chickens, and then burning the chickens to cover the evidence.

[Music]

Pomerantsev: It’s something right out of the sort of absurdist stories that you hear about politics in Eastern Europe, where the regime is using absolutely nonsensical charges against you, and their very absurdity shows that you’re kind of powerless to fight back. Because how do you fight back against somebody accusing you of feeding chickens with election ballots?

Applebaum: Right. This was the kind of archetypic, absurdist thing that happened in communist Poland or communist Czechoslovakia. You know, you would be accused of something ludicrous or ridiculous, and there would be no way to defend yourself. But the whole system would somehow take it incredibly seriously.

Pomerantsev: You can’t actually fight back against absurdity. It’s actually very—well, let me put it differently: It starts off funny, and then it becomes really creepy.

I kind of always thought, just like you did with birtherism and with conspiracy theories, that in the U.S., false accusations would be quickly knocked down by the press—just by the system that is, at the end of the day, grounded in some sort of rationality. Or at the very least, I kind of thought that somebody like Stephen Richer—who, well, let’s put it very basically, is a white election official, not a particularly vulnerable member of society—that they would be able to defend themselves pretty easily against blatant lies. But that is not what was happening at all.

Applebaum: No, in Maricopa County, which is a completely ordinary part of America, we see not just accusations of fraud but ridiculous accusations of fraud, and they were being taken seriously.

Richer: I remember vividly one of the meetings I went to in front of a group of about 50 grassroots activists in the Republican Party, and the first question they asked was, Were the tabulation machines in 2020 connected to the internet?

And we had just had three professional elections-technologies companies come in and test that very thing, among other things. So I knew, categorically, as sure as I possibly could, that the answer to that was no. But you could look into their faces and see that that was not going to go down well.

And I said it, and then it turned into just a lot of shouting, a lot of obscenities, and then ultimately following me out to my car.

Applebaum: It got personal, and it got much worse from there.

Richer: A man from Missouri made a phone call telling me, in no uncertain terms, what he thought of me and what he was going to do because I had said that President Trump’s comments were unhinged regarding his allegations that I had deleted the files.

Applebaum: And do you think that the people who criticized you or attacked you—do you think they believed Trump, or had they departed already from any idea of reality, or was it something they said for political reasons?

Richer: The politicians say it for political reasons. I think the people online and a lot of the people from the Republican grass roots of Arizona who email me really believe it. And it conforms to what they want to believe about the world, which is, I think, a real victimization right now and an explanation of how they lost in 2020 that isn’t simply that more Arizonans voted for Joe Biden, because I don’t think they want to embrace that possibility. And it’s incompatible with the world that they see around them when they go to Trump events and see Trump flags, and their neighbors voted for Trump.

[Music]

NBC 12News newscaster Tram Mai: It appears to be official. Arizona’s attorney general has opened an investigation into the 2020 presidential election. Former Maricopa—

Richer: Mark Brnovich was somebody that I was on friendly terms with, and he had told me that he knew it was all nonsense, but we moved more and more apart as he continued to indulge it. And then, in the late months of 2021, he launched a criminal investigation into the 2020 election over six months.

Pomerantsev: So, Anne, how did we actually get here? There’s a statement from then-President Trump. Then there’s pilgrimages from national figures to Maricopa County.

Applebaum: Exactly. This is where rumors and talk transformed yet again, not just into dramatic pilgrimages and pressure campaigns but now into an actual criminal investigation by the Arizona attorney general.

Richer: He committed 10,000 man-hours to investigating it. It is especially scary to think that somebody who is willing to indulge these delusional beliefs could have been the chief prosecutor for the state of Arizona.

Pomerantsev: Anne, I just can’t help feeling there’s a bigger story here. It’s not about just what happened in Arizona. It’s about: How did something so unhinged, something so absurd become so normalized in the Republican Party?

Applebaum: There are a lot of people, including a lot of Republicans, who are trying to understand that. That’s after the break.

[Music]

Applebaum: Peter, Adam Kinzinger is a former Republican congressman in Washington, where a lot of examples are set that then trickle down to state and local politics. Kinzinger was in office from 2011 to 2023, and he saw the changes in the party as they were happening, and he played along with them a little bit himself, at least for a while, before changing his mind completely.

Adam Kinzinger: Yeah. So, you know, I was raised during the time of Reagan, when I started to pay attention to politics and, you know, always just really believed in the role of America. I grew up hearing that America is this force for good. You know, I was alive during the Soviet Union. I saw, at a young age, the Berlin Wall fall. I saw the iron curtain torn down. And I gave credit for that to the Republican Party, you know, the party that was unabashedly pro-America.

Applebaum: Peter, Kinzinger was very idealistic, like many people who join Congress. But then he discovered that the reality of politics wasn’t always so noble and that, to be part of the party, sometimes you go on TV to say things that rally the base.

Kinzinger on TV recordings, overlapping: Yeah, well, look: This is obviously a reason why I think we need real border security—

—but that ISIS has grown to where it even eclipses Al Qaeda—

Congress may be unpopular. Look, we all get that. We understand it. But that doesn’t mean Congress doesn’t exist. That doesn’t mean you conveniently get to throw out the Constitution.

Applebaum: Kinzinger’s ability to speak for the party on TV and elsewhere got more complicated because right after Donald Trump’s inauguration—immediately—Trump started saying absurd things about how he’d had the largest crowds in history. No one had ever seen so many people on the National Mall.

Kinzinger: Yeah, just shortly after that, you know, dismissing what we see in pictures.

Pomerantsev: The pictures showed that it wasn’t a very big crowd out there. So, you know, he was sort of saying that to be part of his group, part of this new political in-group that rules the country, you’ve got to repeat these absurd statements, and that will show that you’re one of us.

Applebaum: Exactly. In this case, it was ridiculous. I mean, who cares how many people were at the inauguration? But he insisted that his press spokesman get the National Park Service to lie about how many people there were, because only through forcing people to lie, forcing institutions to lie, could he prove their loyalty. And this is another classic piece of authoritarian behavior.

Pomerantsev: Authoritarianism doesn’t start with something huge. It’s like taking or giving a tiny, little bribe—five bucks or something. It doesn’t sound like a big thing. But that’s it. You’re hooked. And then it’s just like cotton candy. It reels you in. It just gets bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger.

Applebaum: Right. So all the while, Adam Kinzinger was increasingly forced into a kind of mental gymnastics. He did, for a while, continue to go on TV, speaking for the GOP on issues that he cared about but without fully aligning himself with the commander in chief.

Kinzinger on TV recordings, overlapping: I agree with what the president’s saying about Iran. I think him pulling out of the nuclear deal was huge. Iran has, by the way, about 40,000 troops in Syria.

Obviously, I think there’s some things I wish he wouldn’t put on Twitter. But when it comes to some of these issues, like with North Korea, I think there’s benefit in that unpredictability—

I wish what the president wouldn’t do is show any kind of division with his intelligence chiefs. I think it’s not beneficial for us. It’s not beneficial for our presence on the world stage.

[Music]

Pomerantsev: You can really hear Kinzinger trying to find a way to be loyal to his party and yet keep his integrity and criticize the leader.

Applebaum: And he continued to try and find that balance, but he found less and less camaraderie among members of his party, especially as the investigation into President Trump’s ties with Russia began.

Kinzinger: This was during the Russia investigation. This person—all I remember is they were a sane, rational person—just said, Yeah, but I think the Democrats are making this up to go after him.

And I remember specifically thinking, You know that that’s not true. But then I started to understand, like, you can convince yourself of anything. If you have to rationalize your behavior, you can convince yourself of anything. So if you know that you have to defend Donald Trump, despite his ties to Russia or his sympathy to Russia—if you know that and, you know, that’s hard for you to do—you can convince yourself that the Democrats are making this up.

You can start out doublespeaking and saying one thing to one group and another thing to another. But, eventually, even the leaders, even those pushing out the false narratives, eventually they get corrupted too, and they believe their own garbage. And that’s a very dangerous moment.

Pomerantsev: It’s a dangerous moment and also sort of the infection of mental corruption spreading. I saw the same thing happen in Russia as it tipped into being a full-blown autocracy.

It was around 2014. I remember the moment very clearly: Russia had just invaded Ukraine, and people that I knew who worked in state media and the bureaucracy—who’d always been so cynical, sort of smirking when they repeated the government’s lines, signaling that they knew that all the propaganda was a stupid game, that they were just playing along—suddenly, when the war started, they had this completely blank look and this total seriousness as they repeated the government lies, that the revolution in Ukraine, which was this incredible act of heroism by the Ukrainian people, was, I don’t know, all a CIA plot. I kept on looking for their old smirk—the little glint in the eye—but suddenly they were just delivering it like zombies. Something had changed. They knew now that they had to inhabit these lies fully if they were going to survive in a new paradigm.

Applebaum: And this vulnerability to mental corruption is very human. It’s just like what happened in 2015 when the plane-crash conspiracy theory in Poland started to take hold.

Pomerantsev: This is the plane-crash conspiracy that the former government had actually been—what? Brought down by—

Applebaum: The president’s plane crashed carrying a lot of military and political leaders as well. And the plane crash was an accident. It was extensively investigated. The black boxes were found. There had been a pilot error.

But then, the late president’s brother, who was also the leader of what was then the political opposition in the parliament, began claiming that the crash was deliberate—maybe it was caused by his political rivals, maybe by the Russians. A lot of people dismissed this. There was no evidence for it.

But once there had been a change of power—once the president’s brother’s party was in charge of the government, the conspiratorial party—then all kinds of people suddenly thought, Well, you know, they won. They must be right. The conspiracy must be true. And even if it’s not true, it’s in my interest to repeat it. And then they began to repeat the same lies as the people in charge.

Pomerantsev: “Truth,” and I’m saying that in inverted commas, becomes whatever the powerful say it is. I’m often asked, like, Do Russians believe in all the lies that Putin’s propaganda says?

Applebaum: And it’s completely the wrong question. Completely wrong.

Pomerantsev: Exactly. It’s the wrong question. Because, you know, if you think about belief as, you know, a set of beliefs that you’ve thought about and you’ve worked out and you’ve decided that represents you—you know, these are your thoughts, what you stand for—I mean, that matters in a society where your opinion matters.

But here it’s the other way around. You say that which marks your belonging in order to feel some sort of psychological comfort. But tomorrow if the line changes, well, then you’ll believe that.

[Music]

Kinzinger: You look at Nazi Germany, and you’re like, How could an entire population of Germans do what they did? And I understand it now, because if you’re living in an environment where there’s so much pressure, you can convince yourself of anything. I’m not comparing Republicans to Nazis, but I can see now how, when that pressure is so intense, you can convince yourself of anything simply to survive.

I have come to believe in my life that people, more than they fear death, they fear not belonging. I think there are more people that would step in front of a train to save a child than there are people that would be willing to leave their party and be an outlier.

Pomerantsev: For me, I find it somewhat petrifying because basically this means a political system where truth and facts and evidence—they aren’t a currency anymore. You can’t have a democratic debate about anything, really. What Adam Kinzinger is talking about here, it’s a very, very anxious moment. And I’m not quite sure how you go back from that moment.

Applebaum: And, of course, it’s also true that once you aren’t having a conversation about reality, you’re not talking about things that have actually happened, then you’re in a different kind of political conversation. Then all you have is anger and emotion and people expressing themselves in order to confirm their identities or to attack somebody else’s identity.

And then you’re not talking about health care or roads or how to build bridges, where the next investment should be or how high taxes are. Instead, you’re in a different kind of politics. And I do think that America crossed into that world.

Pomerantsev: There might be something else going on as well, because at some level, you know, people who are inhabiting this anti-fact, anti-truth identity—at some level, they must always know that that’s not quite them. You know, even if they’re now performing it very seriously, they’re still performing it.

Applebaum: And so you’re saying there’s a psychological cost to having a kind of double life?

Pomerantsev: And when they see someone like a Kinzinger calling them out, saying, Hold on. You weren’t like this before. This is not true, then that sort of just causes this sort of visceral anger.

Applebaum: Yeah, I think it’s anger because someone like Kinzinger is letting down the side. But also, he’s able to say things in a freer way, and there’s a kind of jealousy there as well. That’s also the moment when he was ostracized. And for Kinzinger, it finally happened when he made his decision to vote for the impeachment of President Trump.

CBS newscaster Anthony Mason: “Congressman Adam Kinzinger, one of the growing number of House Republicans to publicly say they will vote to impeach the president. He joins us now.”

Kinzinger: To me, I think by the time that impeachment vote came up, I was blown away that it was only 10 of us.

I mean, you know, when I broke with the GOP—yeah, I guess there’s any number of ways people react. Some were confused. Did you become a Democrat now? Are you a Democrat? Like you only have two options or something—like, you know, the idea of being somebody that actually could think for yourself was foreign to these folks.

And so when you make the decision to go against the party, to leave the party, first off, you realize who your friends are, and then you realize you don’t have near as many as you thought you did.

Applebaum: Can you remember any specific people who dropped you or who were nasty to you?

Kinzinger: Oh yeah. You know, the guy I fought with in Iraq sent me a text that said, I’m ashamed to have ever flown with you.

Applebaum: Wow.

Kinzinger: And there was nothing about our friendship or our time in Iraq together that was political. We fought the enemy. But all of a sudden, he’s ashamed to have fought in a war with me because—what? He disagrees with my political stand?

Applebaum: What Kinzinger found when he was speaking freely was not only did his relationships with people around him change but his whole life became much more dangerous.

Kinzinger: We had people, you know, all in the name of Christ, for some reason—and I say this as a Christian. It’s embarrassing to me for people to say that they want the Lord to strike me and my family down. Why? Because I told you the truth? Because the Bible I looked at, the truth was what you’re supposed to be telling.

People wishing my son, who was six months old at the time, would die. I mean, these are the kinds of things that you just, like—you realize the rot in people’s lives. But I was less concerned about those making calls and leaving messages when they’re drunk on Fox News than I was about the people that wouldn’t bother calling. Because, to them, it would be some just battle to go and kill a congressman, right?

[Music]

Pomerantsev: And, I mean, it’s kind of extraordinary in all the worst possible ways. A U.S. congressman in the United States of America who’s afraid that he’ll be murdered because he refused to go along with a set of utter lies about the 2020 election and the assault on the Capitol. And, you know, one has to feel for Kinzinger and kind of admire him. But he was experiencing these threats at a really high level.

And I can’t forget about the story we started with in Maricopa County in Arizona: Stephen Richer. In a sense, he was far more vulnerable there, and he and his team were having the full weight of the Republican law machine come down on them.

Applebaum: I asked Stephen Richer to talk to me about that.

Applebaum: How did this impact your day-to-day life? Did your commute to work change? Did you think differently about trips to the grocery store or anything like that?

Richer: We took certain precautions at our homes. We built a new security system. And security just got baked into the elections-administration puzzle so much more, such that all of our facilities are just very secure facilities now.

I would say the biggest impact it’s had is just where I go. I don’t put myself into some of the places where, quite frankly, I feel I need to be speaking because they need to be hearing some of this—places where I don’t know if it would be smart, and it certainly wouldn’t be fun.

Applebaum: Meaning places where there are Republicans?

Richer: Like the grassroots groups, you know, where it’s a gathering of 50-plus people who are, you know—they’re angry. They’re angry about life. They’re angry about the world. They’re certainly angry about the 2020 election. And certainly a lot of their anger has been directed towards people like me.

Applebaum: Not all this anger just stays in people’s heads. You have the attempted murder of Congressman Steve Scalise in 2017; the plot to kidnap Michigan’s governor, Gretchen Whitmer, in 2020; a gunman outside the home of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in 2022. And also, in that same year, a man broke into Nancy Pelosi’s house intending to kidnap her and wound up smashing her husband’s head with a hammer instead.

Pomerantsev: And then, of course, this summer, a 20-year-old in Pennsylvania tried to kill Donald Trump at a rally. The bullet grazed his ear.

Applebaum: But all of these examples involve big names—congressmen, Supreme Court justices. In Arizona, we’re talking about local government workers. This is a county election office. And yet, Richer and his team in 2021 are being questioned and harassed and threatened and even investigated by the state’s attorney general, under pressure from the president of the United States. And this was really hard on Richer’s staff.

Richer: There’s a number of people for whom this was a job, and they found it on a county website, and they like the people that they’re working with. They like that it’s consistent. And it rattled quite a few people. Some of them would come to me, just alarmed: Am I going to be arrested?I didn’t do anything.

Pomerantsev: Anne, this is a really important moment, where it’s not just about conspiracists believing their own reality. They start to force it onto other people. People start feeling really awkward and guilty and start internalizing the guilt. I mean, a bit of your brain starts going, Well, did I do it? What if they’re right? What if two plus two equals five? What’s going on here?

Applebaum: It’s unsettling, and people talk about it years later and don’t always recover. I mean, the moment when they were afraid of being arrested for some absurd political claim, the moment when they were forced to say something or do something they didn’t believe—these are moments when you suddenly feel a sharp break with what’s supposed to be normal and what life is supposed to be like.

[Music]

Pomerantsev: Let’s be frank: People get accused of murders they haven’t committed. I mean, there’s all sorts of horrible things that happen, even in the most, you know, advanced democracies. So these things happen.

What’s happening here is a political attack on one of the institutions, the electoral commission, that is meant to guarantee the facts of our democracy. So it’s a sort of strategic attack on the infrastructure of reason that supports a functioning democracy.

Applebaum: Well, the infrastructure of reason is still standing in Maricopa County. The Kafkaesque investigation into Richer ended, and the attorney general in Arizona is an elected position. A Democrat now holds the job.

NBC 12News newscaster Mark Curtis: For almost a year, the state’s top prosecutor concealed his own investigators’ reports that would have showed Arizonans that there was no evidence of election fraud in 2020. Now that Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich has left office, his Democratic successor, Kris Mays, released the reports today.

NBC 12News newscaster Caribe Devine: Team 12’s Brahm Resnik is joining us in studio with more on these bombshell reports. Brahm?

NBC 12News reporter Brahm Resnik: Yeah, keep in mind that former—

Pomerantsev: This slew of prosecutions and personal attacks has a very direct consequence on democracy. It means that ordinary people just don’t want to be part of it. They don’t want to work in these jobs without which democracy doesn’t actually happen.

Applebaum: I asked Stephen Richer what he’s doing these days in order to recruit and rehire at the county clerk’s office.

[Music]

Richer: I tell them: You get a front row seat to history. I tell them that 10, 20, 30 years—whatever it is—from now, this will be a chapter in American textbooks. And for whatever reason, of all the bars in all the towns in all the world, Maricopa County figures in prominently to this conversation, and our office figures in prominently.

[Music]

Applebaum:Autocracy in America is hosted by Peter Pomerantsev and me, Anne Applebaum. It’s produced by Natalie Brennan and Jocelyn Frank, edited by Dave Shaw, mixed by Rob Smierciak. Claudine Ebeid is the executive producer of Atlantic audio, and Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

Pomerantsev:Autocracy in America is produced by The Atlantic and made possible with support from the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University, an academic and public forum dedicated to strengthening global democracy through powerful civic engagement and informed, inclusive dialogue.

[Music]

Applebaum: I suppose that was a happy ending of a kind. Although, this summer, Richer lost a Republican primary. The investigations ended, but many Arizonans continue to believe that the 2020 election was stolen.

Pomerantsev: What happens if the courts are undermined and are willing to go along with that conspiracy? What if the psychological corruption becomes political corruption? What if the online mobs shouting about conspiracy theories and the people calling congressmen to threaten their children—what if those people get control of a congressional committee, a government department, or a courthouse?

Applebaum: It’s beginning to happen already.

Renée DiResta: That, for me, was a real Oh, wow moment, because I thought, Surely, we’re not that far gone. And then, yeah—and then I realized, Maybe we are, actually.

Applebaum: That’s next time on Autocracy in America.