The Trap of Making a Trump Biopic

5 min read

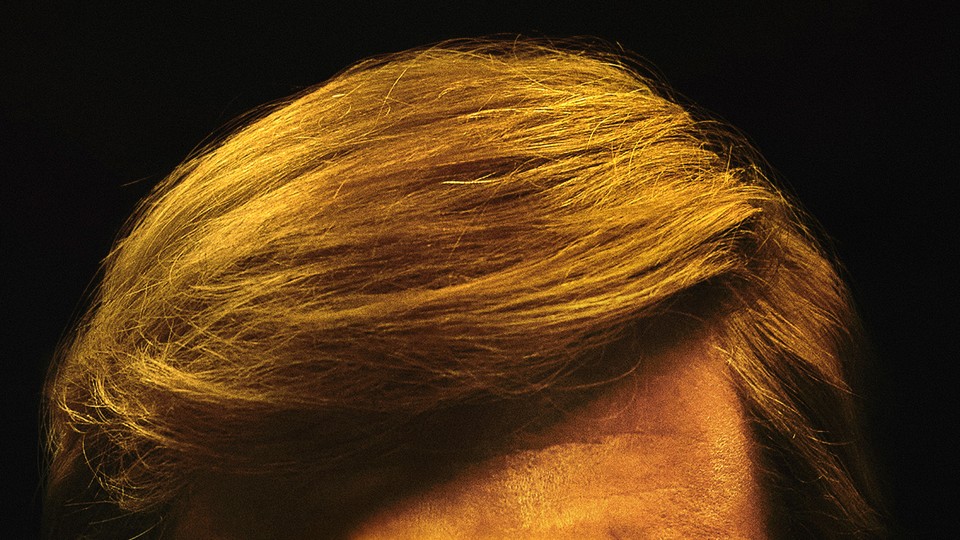

As the young Donald Trump in the new film The Apprentice, Sebastian Stan slouches while he walks, pouts while he talks, and delivers every line of dialogue in a near monotone. Such behaviors tend to form the foundation for any recent Trump performance, but Stan delivers more than a comic impression. He finds complexity in these hallmarks: an instinctual defensiveness in those hunched shoulders, a frustrated petulance in the scowls. It’s precise work, in other words.

If only the film around him were just as carefully calibrated. The Apprentice attempts to chart Trump’s rise from real-estate businessman to future presidential candidate by focusing on his early career in the 1970s and ’80s, when, under the tutelage of the pugnacious lawyer Roy Cohn (played by Succession’s Jeremy Strong), he learned how to project power and not just crave it. The film is a muddy exercise in Trumpology that never answers the biggest question it raises: What does chronicling Trump’s beginnings illuminate about one of the most documented and least mysterious men in recent American history?

Not much, as it turns out. Yet the film struggled to find a U.S. distributor willing to back it during production; Trump is a polarizing figure, after all, and famously litigious. After its debut at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, The Apprentice indeed faced legal threats from the Trump campaign, leaving it languishing for months in search of any company that might help it reach American audiences—the ones most likely to see, and be affected by, the film. Briarcliff Entertainment, a small company that has begun to develop a reputation for picking up controversial projects, stepped in and launched a Kickstarter campaign to crowdfund the movie’s theatrical run, which begins Friday.

But the director, Ali Abbasi, an Iranian Danish filmmaker whose previous film, Holy Spider,turned a real-life serial-killer case into a fascinating drama, has insisted that The Apprentice isn’t meant to truly be about Trump; rather, it’s an outsider’s perspective on America through its most divisive avatar. “We wanted to do a punk-rock version of a historical movie,” Abbasi told Vanity Fair, citing Stanley Kubrick’s transporting epic Barry Lyndon as an inspiration. He, along with the screenwriter Gabriel Sherman, a journalist who has long covered Trump, intended to “strip politics” from the story altogether.

The idea of a politics-free film about Trump may be provocative to some viewers, but The Apprentice never quite achieves this goal. The action unfolds in two parts: In the first, the 20-something Trump, still attempting to carve out a real-estate career and climb the social ladder, is dazzled by Cohn’s celebrity. He tails him around New York City for much of the 1970s while absorbing Cohn’s three tenets for success: Attack, attack, attack; admit nothing, deny everything; and claim victory, never admit defeat. In the second part, Trump has come to embody those rules fully. It’s only a two-year time jump, from 1977 to 1979, yet it feels jarring, because the Trump of the ’80s is more ruthless than Cohn ever was. And that decision, to skip past depicting his shift toward callousness, prevents the film from fulfilling Abbasi and Sherman’s aim of interpreting America’s transformation. It drops plenty of tasteless hints at present-day Trump instead: A scene of him being intrigued by the potential new slogan for Ronald Reagan’s first presidential campaign—“Let’s make America great again!”—is played for laughs. When, during an interview, he scoffs at the prospect of launching a political campaign himself, the shot holds for an extra beat, as if daring viewers to chuckle along with him.

By omitting the years when Trump started coming into his own, The Apprentice delivers a summary of his character rather than an arc. Take his relationship with Ivana (Maria Bakalova), for instance: In the film’s first half, Trump is a hapless suitor, literally falling over during an attempt to impress her. In the second half, he is seen assaulting his now-wife in their home in a violent scene that likely drew the Trump campaign’s ire. (The scene is based on Ivana’s recounting of an incident in a 1990 divorce deposition, which she later recanted; Trump also denied the allegation.) The contrast underlines the difference between a power-hungry man and an actually powerful one, but it doesn’t show us the trajectory itself. The Apprentice suggests that Cohn hastened whatever rot was already present in his protégé, but its early scenes portray the opposite—that Trump, at his core, was simply naive. He desperately attempts to contribute to his family’s real-estate business; he idolizes his older brother; he displays a simpering loyalty to Cohn. Abbasi may have wanted to avoid putting his finger on the political scale—to steer clear of sympathy or condemnation—but the result is a shallow, murky portrait.

Perhaps this lack of substance is meant to evoke the flimsiness of the TV show the movie is named after. But The Apprentice offers glimmers of more nuanced ideas. It is handsomely shot, the production design making 1970s New York look like it’s in a state of decay, with the grime extending to the staging: Trump, in one of the earlier, more dynamic scenes, corners Cohn in a bathroom to convince him of his worth. The best parts of the film engage with how Cohn boosted his own ego and drew considerable pleasure from molding Trump into his image; Stan and Strong deliver committed, electric performances in their scenes together. But the energy fizzles when The Apprentice descends into a supercut of the younger Trump’s lore. It re-creates some of his most braggadocious interviews. It shows his reported scalp-reduction surgery. It ends in 1987, with him meeting the ghostwriter of his memoir. When an ailing Cohn finally confronts Trump for avoiding him, the encounter feels perfunctory, a mere interruption of an extended clip show.

The Apprentice could have delved into the Trump persona or explored how it calcified. But by trying to avoid how Trump’s past reflects his current approach to politics—his zero-sum relationship to power, his pettiness and egotism—while simultaneously winking at viewers’ knowledge of him, the film lands itself in a trap. Abbasi and Sherman’s intent—to hold today’s Trump at arm’s length and dramatize his backstory in “punk-rock,” cheeky fashion—is inherently flawed, because separating Trump’s philosophies from his transformation as a public figure means dulling the story of any potency or relevance. Even the one relationship, between Trump and Cohn, that feels potentially insightful gets diminished by the end. The film becomes an exhausting reenactment of familiar events instead—a safe endeavor that coasts on its protagonist’s infamy.