The Everyday Warfare of Voting in America

10 min read

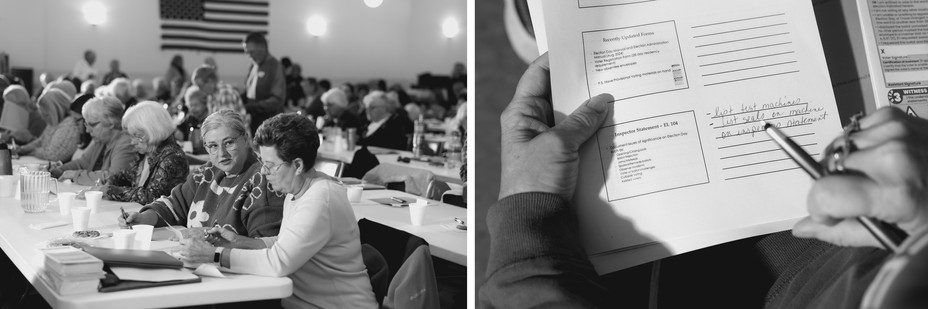

When Melissa Kono, the town clerk in Burnside, Wisconsin, began training election workers in 2015, their questions were relatively mundane. They asked about election rules, voter eligibility, and other basic procedures. The job was gratifying and enjoyable; they helped their neighbors while sipping coffee.

But over the past few years, everything has changed. Kono now finds herself fielding questions about what to do when approached by suspicious voters who ask provocative questions or gripe about fraud. She’s added an entire training section dedicated to identifying threats and how to report them. “I never in a million years imagined that that would be part of my curriculum,” she told me. Kono has yet to receive any direct threats herself—perhaps, she thinks, because Donald Trump won the popular vote in her area in 2016 and 2020—but she fears that things may be different this time around. “What I do hear is I know the election is not rigged here, but in other places,” she said. “And I’m honestly worried sometimes: What if Harris wins? What if it gets too close? And now they start questioning me or coming after me, when I have nothing to do with the outcome.”

Around the country, election officials have already received death threats and packages filled with white powder. Their dogs have been poisoned, their homes swatted, their family members targeted. In Texas, one man called for a “a mass shooting of poll workers and election officials” in precincts with results he found suspicious. “The point is coercion; the point is intimidation. It’s to get you to do or not do something,” Al Schmidt, the secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, told me—to get you to “stop counting votes, or we’re going to murder your children, and they name your children,” a threat that Schmidt said he received in 2020. This year, the same things may well happen again. “I had one election official who said they called her on her cellphone and said, ‘Looks like your mom made lasagna tonight; she’s wearing that pretty yellow dress that she likes to wear to church,” Tammy Patrick, the chief programs officer at the National Association of Election Officials and a former elections officer in Maricopa County, Arizona, told me. “It’s terrorism here in America.”

These workers, from secretaries of state to local officials to volunteers, are bearing the immediate, human toll of a campaign to discredit the integrity of American democracy. They are the most direct and vulnerable targets for people who have embraced conspiracy theories about fraudulent and “stolen” votes following the 2020 election—unfounded claims that have been directly promoted by Trump and many other members of the Republican Party, who still will not accept that he lost his first reelection bid. Where candidates used to compete against each other, Schmidt told me, some are now “attacking the referees.” In the most extreme narratives, election workers are accused of fabricating, shredding, or double-counting ballots, which leads to suspicion and harassment. “Since the 2020 election, we have seen an unprecedented spike in threats against the public servants who do administer our elections,” including shootings and a bomb threat, Attorney General Merrick Garland said last month. A survey conducted in February and March by the Brennan Center for Justice found that 38 percent of election officials reported being harassed, abused, or threatened—up from 30 percent a year earlier.

This is not just a story about assaults on individual workers, although that would be bad enough. Election administration is “underappreciated as the foundation upon which all of our representative government thrives,” Rachel Orey, the director of the Bipartisan Policy Center Elections Project, told me. In a very real way, these officials represent the soul of democracy. Many of them are undertaking their duties while also juggling child care and everyday errands such as grocery shopping. Without their diligence, nobody could be elected, period. The form of government that Americans recognize and celebrate could not exist.

Dissuading or preventing people from going to, or otherwise attempting to interfere with, the polls are century-old dirty tactics, and there are all manner of legal ways to suppress or dilute the vote, many of which target racial minorities. But Trump’s attempts to unilaterally dictate election results are different. As far back as 2012, he criticized Barack Obama’s reelection as a “total sham and a travesty.” Victory in 2016, and the conversion or defeat of nearly all of his Republican rivals, gave Trump the power to mount a serious and systematic attempt to discredit the democratic process. He and his furious supporters, in turn, have unleashed a sustained assault on national and state elections alike.

“I wasn’t aware of any real threats or harassment or wide-scale verbal abuse on election officials prior to the 2020 election cycle,” Tina Barton, the vice chair of the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections, told me. The outrage and attacks that emerged in 2020 have now been harnessed into a well-funded campaign: Republicans have reportedly donated upwards of $100 million to a network of so-called election-integrity groups to lay the groundwork for contesting the results should Trump lose again. Although poll watching is itself normal, the GOP is training and deploying armies of monitors with the presumption of fraud, flooding election offices with public-records requests, and filing endless challenges to voter-registration records. “I don’t think there’s any question that there is a more coordinated and sophisticated effort ahead of this election to discredit it than there was in 2020,” Lawrence Norden, the vice president of the elections and government program at the Brennan Center, told me.

This election cycle, one of the “dominant narratives” is about noncitizen voting, Thessalia Merivaki, a political scientist at Georgetown University who studies how election officials combat misinformation, told me. Republican activists, politicians, lawmakers, and pundits have especially seized on false fears about immigrant and foreign voting to burnish a conspiracy theory that noncitizen votes from overseas will turn the election. These claims have been widely debunked, but all the energy behind them could delay vote counts and disenfranchise citizens. Republican groups are filing more and more lawsuits in battleground states about voter-identification requirements, absentee ballots, and other basic procedures, “setting up an opportunity afterwards to cast doubt on the election results,” Norden said.

When I began reporting this article, I was curious about whether election officials had concerns over new technologies. The internet has changed substantially since 2020. For the past couple of years, I’ve written about the rise of generative AI and its attendant issues: In terms that are most directly relevant to the election, that means the arrival of easy-to-create and highly convincing deepfakes, the concoction of micro-targeted conspiracy theories, the overall degradation of our information environment, and the possibility that our sense of shared reality might be wiped out altogether. It’s easy to imagine that AI could wreak havoc around Election Day—earlier this year, a robocall that cloned President Joe Biden’s voice was used in a voter-suppression effort—and experts have made their concerns about the technology clear.

The election workers and officials I spoke with did express worry about AI and its ability to accelerate disinformation and election-interference campaigns. But they also described problems that came from more familiar sources. They spoke with me about how videos of entirely proper and legal election procedures—snippets of livestreamed election procedures, for instance—had been miscontextualized to suggest that officials who were simply following the rules were actually smuggling in ballots, rigging voting machines, or otherwise manipulating the results. Blatantly false headlines and incendiary posts spreading on messaging apps and among social-media groups have done and continue to do plenty of damage. Sometimes, the details are irrelevant. As my colleague Charlie Warzel recently wrote, manipulated media and misinformation is useful not necessarily because it convinces some population of undecided suckers, but because it allows the already aggrieved to sequester themselves in a parallel reality. A voter might say, “Let’s just set the facts aside,” Patrick, of the National Association of Election Officials, told me, “and I’m going to tell you what I think or what I feel about this.”

Amy Burgans, the clerk-treasurer in Douglas County, Nevada, herself had doubts about the outcome of the 2020 election when she started in her role that December. (The previous clerk-treasurer had resigned—the pandemic and contentious election cycle, Burgans told me, had been “a lot.”) Burgans said that she had heard in the news, on social media, and from people she knew that there “must have been” some foul play. But once she was in charge of running elections and administered the 2022 midterms, she said, she saw the rigor at every step of the process and understood that the allegations of widespread, systemic fraud were impossible.

Now she’s the one fielding questions, frequently about voting machines. Burgans has explained to voters all of the controls in place, that she’s “never seen even one error” after an election audit. Still, people ask her about election procedures at almost every event she attends, or “even if I’m at the Elks Club just hanging out,” she said. Burgans said she has “no issues with” and tries to address these questions. But doing so takes time and energy—and these comments are just the tip of the spear.

Burgans received a threat in the mail in 2022. Although it was mostly a broad rant about the government, it did make her worry for her children’s safety, and she installed a security system in her home. Her county’s election facilities are stocked with personal protective equipment and Narcan, in the event of suspicious substances or powders (which might be Fentanyl) arriving in the mail—something that has already happened at election offices in several states. She also recently installed bulletproof glass in the office, where Burgans and full-time staff work—as a precaution rather than a response to any particular threat, she said. Election deniers are “consistently coming into [election] offices saying things like ‘You’d better watch your back’ or ‘Don’t you forget: I know where your kids go to school,” Barton, the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections vice chair, told me. What was unprecedented in 2020, Barton said, is now an “ongoing onslaught.”

This attack on American elections is not an invasion so much as a siege. And just as hateful, outlandish, and conspiracist misinformation have eroded Americans’ trust in one another, institutions, and basic facts, this environment is taking a psychic toll on election workers. They find themselves having to put in extra hours to field questions, accommodate an influx of poll watchers, process voter challenges, sort through public-records requests, and prepare for any emergencies and attacks—all while fearing for their safety. For more than two decades, running an election has become steadily more complex and involved. After 2000’s infamous hanging chads, election workers had to become IT professionals. After long lines became a key issue in 2008 and 2012, they became logistics experts. After 2016, they learned cybersecurity, and in advance of 2020, they studied public-health protocols and how to process enormous quantities of mail-in ballots. Now election workers have to be communications experts as well. “We’ve had poll watchers in here every single day since September 26,” when early voting began, “sometimes three or four of them in a small space,” Aaron Ammons, the clerk and recorder of deeds in Champaign County, Illinois, said in a recent press briefing.

Meanwhile, support and resources for these emerging responsibilities are frequently missing. The result, inevitably, is burnout: The job keeps getting harder and requiring more hours, but resources for hiring, buying new equipment, improving security, and more have been inconsistent and haphazard. “There have been new challenges and new expectations put on election administrators, but funding hasn’t kept pace,” Rachel Orey said. Hours spent on election work have ballooned since 2020, according to a recent national survey of election workers conducted by Reed College. Meanwhile, nearly one-third of election offices don’t have any full-time staff, wages are pitiful, and turnover rates grew from 28 percent in 2004—already high—to nearly 39 percent in 2022.

This burden “has taken away from [election officials’] ability to just focus on the mechanics of that very important election,” Kim Wyman, a former secretary of state for Washington who recently served as a senior election-security adviser at the Department of Homeland Security, told me. Skeptics will use innocent mistakes and logistical snares—which are mundane and easily rectified—and even the act of correcting “as gasoline on the fire to ‘prove’ their point or their claim of voter fraud,” she said. This, in turn, only fuels the exhaustion. “People just make up stuff about what we do and are coming after us,” Kono, of Wisconsin, told me. She’s seen many longtime clerks and election workers leave, telling her, “I can’t do another presidential election” and “I don’t want to have to deal with voters.”

Those who remain do not take the job lightly. In 20 years working in election administration, Barton told me, “I have never seen election officials train so much in four years’ time”—improving security, being transparent at every step of the process, speaking at events and posting on social media to educate their communities. They’ve been preparing for November 5, 2024, for four years, Wyman told me. “This is my Olympics,” Kono said.

The misinformation crisis is commonly understood as a clash between two “realities” that is most visible online, in the words of high-profile politicians, or during spectacular flashpoints such as the January 6 Capitol riot. But for four years, and especially in the weeks leading up to and after November 5, these battles have and will be quotidian and interpersonal. “We are your soccer coaches. We are the moms helping at the schools, the dads coaching baseball, the grandmothers that are going on field trips,” Burgans said. This everyday warfare, waged against the neighbors and teachers and elders and bus drivers who administer the polls, and in turn democracy, may be more consequential than any single vote or outcome.